[Georges] Duhamel calls the movie “a pastime for helots, a diversion for uneducated, wretched, worn-out creatures who are consumed by their worries… a spectacle which requires no concentration and presupposes no intelligence… which kindles no light in the heart and awakens no hope other than the ridiculous one of someday becoming a ‘star’ in Los Angeles.” (Benjamin, 1999)

Can we consider celebrity as a material? The idea of celebrity as material emerges from the ashes of the mimesis paradigm of art—the hoary assumption that art should imitate, copy or represent reality—which was extinguished during the twentieth century.

The advent of the readymade, most famously Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), and the reproduction of commercial reality, such as in Warhol’s Brillo Box (1964), captivated artists because these works eschewed the notion of mimesis that had dominated painting and sculpture in the Western tradition since Plato.

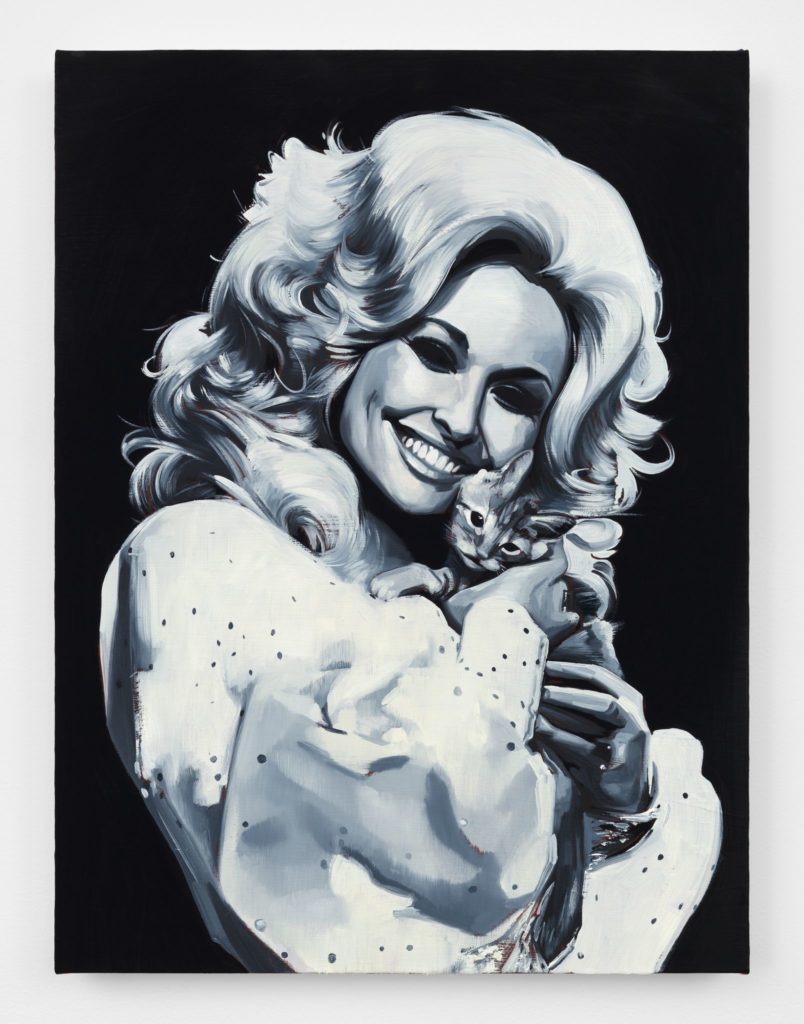

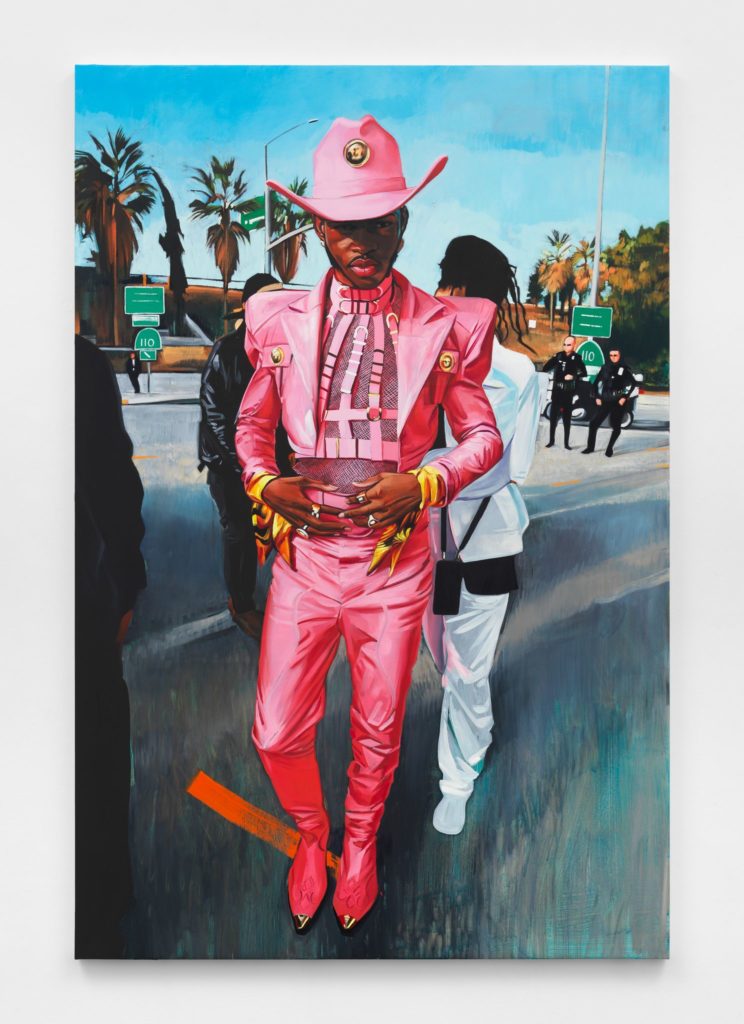

However, once art ceases to be mimetic, the notion of a portrait as a representation of a person becomes destabilized, enabling the portrait to investigate concepts such as celebrity as well as appearance. Three basic approaches to celebrity in art help to elucidate this claim: Warhol’s manner of repeating the image of a celebrity in manifold different forms, David Bailey’s painterly eye for capturing and solidifying moments in cultural history, and Stella Vine’s dispensation of figuration in the service of untangling the soul. Running in parallel with the shifting notion of celebrity, these three distinct renderings chart the development of celebrity in art from mere subject to full-blown sensationalist material.

Portraiture, as the act of representing people as individuals rather than idealised figures, has always been concerned with celebrity, from Jesus to royalty, but celebrity is in that sense the subject of portraits rather than the material.The idea that a portrait aims to represent a person with some degree of likeness survives most philosophical disputes about resemblance. Moreover, it should be uncontroversial that a portrait aims to capture something of the sitter’s spirit or essence. The resultant image, a representation of the sitter, is heavily mediated by the painter’s view of the sitter, which they have distilled and presented in stasis. The act of making the portrait is as much an act of presenting a fixed view of a fluid, living individual as it is of representing reality.

In the case that the painter has put so much of themselves into the portrait that it is as much or more concerned with artist than sitter, this is where subject becomes material: the sitter remains the subject of the painting, but the artist—their personality, bias, creative choices, worldview—numbers among the painting’s materials. Celebrity thus becomes a material rather than a mere subject, when the portrait is about more than the sitter, when the sitter is used as a vehicle for the expression of a sentiment about the worldview they are taken to represent. In this sense, celebrity is one element among the many that comprise a picture; along with pigment, paint, shape, ink, paper or canvas, it gives the picture structure, form and, crucially, meaning. While portraits that are about celebrity take the surface as their subject, portraits that are made of celebrity embody something much broader.

Warhol is the quintessential portrait artist of the twentieth century. In his depictions of celebrities from Marylin Monroe to Mick Jagger, Warhol uses a combination of basic figuration and textural flourishes that both represent a likeness to varying degrees and manifest some spark of character, even if that character is just the highly mediated public face of the celebrity. In the Mick Jagger (F&S 138-147) series of prints (1975) for example, Jagger’s hair and lips are highlighted because that distinctive shock of black hair and those full, pouting lips are the singer’s symbolic markers.

In repeating the symbolic markers, Warhol is reiterating that the pictures are about those individuals, rather than about artistic process. The repetition of the image—for example, Marylyn Monroe’s face—in different media, colours and formats can be taken to suggest that the pictures are about that repetition as an artistic conceit, just as Damien Hirst’s spot paintings are about the repeatability of the idea in different colours and sizes. But Warhol’s prints are not centrally about the process. Although it is important, the process of screen printing, for example, affords him the means by which he can explore his central interest in Monroe’s face as a repeatable, marketable image of the culture industry.

Or is it?

References:

Benjamin, W. 1999. ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ [1936]. Illuminations, translated by Harry Zorn, edited by Hannah Arendt. London: Pimlico.

Danto, Arthur C. 1992. Beyond the Brillo Box: The Visual Arts in Post-Historical Perspective. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Shirky, C. 2008. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organizations. London: Allen Lane.

Sam McKinniss courtesy of Almine Rech

I have worked as a lecturer, teacher, bookshop manager, gallery invigilator, curator and freelance writer, for the most part simultaneously, which exemplifies a lifelong passion for art, culture and ideas. I was born on the Isle of Wight in the very year that both Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation and Arthur Danto’s The Transfiguration of the Commonplace were published.