Unpicking the properties within this discussion is Professor Brad Evans, an academic and collaborator of artist Jake Chapman, whose work has reached a wider audience by discussing how larger contemporary mythic events (9/11, COVID, Online cultures), as methods of cultural reproduction (why ideas survive and thrive), contribute to the power of the tribal meta-cultural entities (online, interest groups, militias, political parties) framing contemporary life. Around the topic of violence ‘where humanity learns to deal with the insecure sediment of its existence’ (Evans 2017) Evans has traced a historical genealogy of sovereignty from the savage through enlightenment to where we are now, in emancipation. All are terms that require qualification amongst different logics of violence.

Following on from part one last week in this second part of Trebuchet’s discussion with philosopher Brad Evans, he discussions the potential of action and social renewal.

What then is truth? Is it all relative?

First of all, in global politics there’s a sense in which the appeal of Donald Trump was in his having a simple message ‘you can be great again’. He’s the first US president in history to tell Americans they weren’t great. He says, you’re not great at the minute, but you can be great again. That’s quite a profound moment in American politics, but Trump is just a symptom of the state of things. He was just reflected, or capitalised on a yearning for simple nostalgic truths, which has created a bizarre dialectic. I recently co-authored an article which called out the ‘religious left’. It discusses the elements of the left which mirror Trump in their absolute simplicity, an ownership of their ‘truth’ and the inability to see the other side. But it’s also the way that people are vociferous on social media in order to get a bunch of followers. Everything they say claims the world is obvious. Anybody who tells you that the world is obvious is lying to you! It’s not obvious, but that is the point about truth now. So much of it is relative but actually, to me, it seems the ones who are armed with the (apparently) Absolute Truth are running things.

Foucault would argue that to have any sense of a courage to truth, you need to be able to see every single possible interpretation of an idea. Nothing should be censored, nothing should be held back. Nothing should be off the table. You should have that capacity to be truly free in the liberation of an idea, even and especially if they’re honest. If an idea is dangerous, the only way you’re going to become autonomous is to break it apart and find out what it actually means. This is how we can interpret it. We see great examples of this in the art of Frida Kahlo, or more recently, Gilbert and George, or Jake and Dinos Chapman. Without that capacity for outrageousness what does art have?

You can even take it back to Rothko. How outrageous was his work when it first appeared? And Rothko doesn’t give you simple answers. He doesn’t make anything obvious to you, but you go to Rothko, and it’s an assault on the senses. It’s not a straightforward, emotional truth when you’re sitting in the Rothko room at the Tate Britain. But, you leave exhausted. You’re disrupted, and things don’t make sense, because you’ve had a proper immersive experience in art. None of this hyper-digitised stuff, ut rather a real immersion into the depths of Rothko’s vision that is completely unsettling emotionally. The key thing is that you don’t have a clear answer straight after. In such a space, what use would be the obvious truth?

You don’t leave with a direct message?

No, but there’s a message there. There’s something being indicated and it might take you six months, and at some point you’re going to have moments where you might think ‘Maybe that’s what he means’. And in a particular context, aspects of the image come back to you. And that’s how it affects you. It makes you see and experience things differently.

You’ve spoken about Climate change and the colonisation of ideas.

With climate change the balance that we’re presented with is in itself a false balance, which always holds the master signifier of science. While there’s the debate between the science and the dubious person about the science,, what we’re always discussing is the science. This invariably leads us into a situation where every answer is resolved by technology in one way or another. So technology will become the Saviour, whereas I’ve never seen on the news somebody having a fundamental debate about ecology and somebody else saying, ‘Well, use the scientific approach’.

We can all accept that ecological devastation is happening, just put your head outside the window. And you can see what’s happening, it doesn’t take a great deal of science to work out that the world is rapidly transforming before our eyes. But why do we use a scientific approach over a more artistic, poetic approach to climate change? We use one approach, which says, ‘This is all about the science, so let’s leave it to the engineers and the technocrats, they’re going to work it out.’ Whereas another approach would be to view this change as happening to humanity and so to ask whether this means we need to develop a more ethical, artistic, poetic sensibility about what it means to be human in the 21st century?

Why are we in this mess in the first place? Will hyper-industrialization, our faith in technology and machines come to the rescue? Why are we now giving ourselves back over to the machines to save us? Maybe less machinery is better for us? Is that even on the table?

The idea of Leftist accelerationism (that we need more capitalism in order to reach a point where humanism prevails over exploitation and competition) is very interesting right now. On the Leftist side, you see how it completely fits with the ideas of post-humanism and the idea of technologically enabled liberation. Not to mention the fetishization of connectivity, network thinking and so on. And there’s something in that emancipatory idealism of the network form which leads into the idea of a transcendent post-human sensibility.

Having a complete virtualization of those things is a warning sign. And if we want a philosophical anchor for this, we can trace this all the way back to William Blake and the idea of the human abstract. William Blake’s earlier critique of Urizen, the god of technology. Blake was onto this, though he collapsed back into orthodox religion, which he saw as humanity’s exit point.. I’d argue that we’ve entered into a new chapter, which is that the history of violence is a history of battle over different sacred objects. History is a long continuum of religious war, and we go through different stages of religious war.

At this stage we’ve entered into a new chapter which is defined by what I’ve called the ‘planetary techno theodicy’. Technology is now the dominant religion for our times, technology promises to be the salvation, the redemption, to save humans from themselves, and so on. But what we’ve done is engage in what Zygmunt Bauman calls ‘retro-topia’. We’re constantly harking back to this retro-topic idea of the perfect time that never was, the golden age of American cinema or something like that. The photographs of Margaret Bourke-White depicting the long lines of people in the Deep South queuing because of the Mississippi Flood, for instance, that’s the reality of the Golden Age.

But for the Left, we’ve displaced utopia with Atopia. Atopia is basically a non place. It’s a non-inhabited space if it doesn’t doesn’t have a firm destination anymore. It lends itself precisely to the Metaverse narratives. The Metaverse is an atopia. It doesn’t exist in time and place in itself. It’s everywhere. But importantly, it’s nowhere in an actionable material sense. Which matters because we are physical beings. You can see again the impetus for this breakdown: the borders break down, attachments and belongings, while promoting a wilderness of virtualised non-belonging. Who does that benefit?

The pandemic is an important moment in thinking about truth. The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben courted a lot of controversy for his criticism of the lockdown. Now, first of all, his commentary on the pandemic was very much misplaced. But then again, being an Italian citizen, who can forgive him for being dubious of the Italian state wanting to claim more exceptional powers for itself (given the history of Fascism in Italy)? For Agamben, the way the pandemic would be used as a foil for the hyper-technologization of life is hard to disagree with now. Do we know the difference any more between the home and the office? Between work time and non-work time? I’m literally inviting students into my living room. Where are the lines between the home, the office, the prison, the, the quarantine centre? It’s all collapsed into one through this process of digitalisation. Reality has collapsed and yet, we are increasingly living these hyper-technologized lives. And the word ‘hyper’ itself is a very instructive word here, because we are all now living this hyper condition: hyper-emotional, hyper-sensitive, hyper-affirmative, hyper-depressive, and it all filters into this atopic space, where you have no sense of grounding, where you can’t just simply step back and go, “Okay, I just need to take a breather. I need to get my bearings, get a sense of the world, get a sense that secure grounding, get a foothold back in the world of reality”. Nobody knows that distinction anymore. I think. And that’s the real problem.

Inhabiting an immaterial existence means we no longer see material ruin. We don’t see the ruins of past things, or the passing of things. The idea of engaging with the ruins is so important in terms of having a philosophy of the passing of time, the philosophy of death.

Are we missing the entropy and erosion of things?

Yes! The things that we hold onto. I gave a lecture recently at Oregon when I was talking about some of the different kinds of violences in the digital world. One of the things I find particularly striking is the trauma around the violence of erasure. First of all, the erasure of age in social media is interesting, where anybody can just take an app and remove the evidence of time. You barely see a photograph of somebody today who hasn’t erased the lines on their forehead. In some senses you’re erasing the marks of history. So I played around with this in the lecture and showed what Samuel Beckett’s face looks like if you take away all the lines. It’s completely uninteresting to look at. What does this mean? And then, of course, you can erase unwanted lovers or former husbands from your holiday photos. Stalin would have loved this technology! What mental damage are we doing to ourselves thinking that we can erase reality in this way? What reality are we constructing ourselves for? Stuff is presented in this hyper-technologized way, as a way of enhancing community, liberating us from the old, dogmatic, introverted communities of the past.

What does that actually mean? It’s actual communities being replaced by connectivity and immediate connectivity in which it’s easy to banish someone. I have conducted culls on Facebook, where you just get rid of 200 people, as if it’s a whimsical thing. And it is! It is a whimsical annihilation. I will just block them or banish them or take them out of the world, whatever…. This has me thinking more and more about the neo-Zapatistas, who leftists saw as the first digital revolution. Bullshit when you now think of it. I remember when the neo-Zapatistas first appeared in 1994. And everybody was talking about the first internet revolution, yet you go to Chiapas and there was no sign of the internet. Sure, there’s a bit of the networked dissemination of messages. But these are indigenous people who take their time to make communal decisions over every aspect of their existence. Zero accelerationism. The one thing I learned from them was everything was about time, you slow things down. You don’t accelerate into this hyper-digitalized world. That is what we’re losing today – the importance of time as a political concept. If there is a central question to me, to art, it’s time. The time to reflect, the time to have a deeper conversation, the time to look, the time to witness. You see that also been eviscerated in galleries and museums where everything has to be imminent, everything has to be an imminent explanation and imminent encounter. In front of you right now with immediate knowledge, immediate truths about things.

The violence that we encounter today is maintained by an imminent psychosis where nobody feels secure. One of the most famous books written in the 1980s about economics was John Kenneth Galbraith’s The Culture of Contentment. Nobody’s content today! We live in an age of the anxious massification, where everybody is constantly anxious about the state of the world without any wherewithal about whether there will be a better outcome or material change. Because there are no material solutions. And it becomes, as you say, the simulacrum, where the overriding incessant focus is on psychological violence. This overrides the actual physical violence, which is still existing, it doesn’t magically cut it away. And that’s why the crisis in Ukraine is so perturbing for us, because it’s a good old-fashioned war. It’s one bunch of soldiers walking across a border, invading a country, and literally, physically, killing people. And it’s a reminder that in the world, despite our attention on virtualisation, real stuff is still going on. It’s still real, it has always been going on, and all this focus into the psychological, hyper Metaverse, reality environments, we don’t like that disruption of the narrative. Quoting The Matrix: ‘Welcome to the desert of the real’. This is the reality of the world as it is, and of course we can say, what happens in the digital world has consequences. Yes, it can have real consequences too, but it’s consequences that are often self-made through the medium itself.

I left Twitter nearly two years ago. Leaving the platform, you realise that 95% of the things that happen on Twitter are about what’s happening on Twitter. It’s like a sort of perpetual motion machine. It just goes on and on and on. Plus, I just found that environment so toxic. It was making me feel anxious. I just think for younger kids who are so immersed, it becomes literally their whole world. So, what does that mean for them in terms of how they learn to deal with people, with crises, what tools are they developing, or not developing? Are we going to find a generation of people with the inability to deal with crises? I find this increasing, incessant drive to promote the active production of self-embracing vulnerable subjects very problematic. Especially when it appears as self-embracing victimisation. It’s purely confessional. It’s purely theological. So everything is a confession.

One of the best things the actor Michael Douglas has done in his career is the series The Kominsky Method. There’s a moment in one episode where he’s going through a crisis and his daughter basically tells him to go and see a shrink and just talk about his feelings. He’s like, ‘Why do I want to talk about all these feelings to everybody?’ At some point we need to keep hold of our secrets. But there’s this constant confessional now and our cultural life is governed by our penchant for controversy. I co-wrote a book a while back called Resilient Life, The Art of Living Dangerously which argues that resilience is an inherently nihilistic concept. It forces us to partake in a world which is fundamentally insecure by design. What this means is yousee disasters as learning processes, and you have to accept the inevitability of another catastrophe. It’s not a philosophy which asks whether there is a way to say ‘Look, hang about, let’s get to the root causes of terrorism, disaster, catastrophism, let’s stop’. No, we are told to just become resilient, learn to bounce back, and that other attacks are inevitable. It’s just like a neoliberal care for the self.

The counter-argument to that is that that philosophy is aimed at people who have become paralysed by so many shocks, so the idea is that, if they take on a form of acceptance, they can go forward, act and make sure it never happens again.

I understand that, but the deeper philosophical point around this is around ontologies of vulnerability, and the ways in which vulnerability has now become the default setting for subjectivity. So we have to accept that we are ontologically vulnerable, that we are fundamentally insecure as subjects by design. And this lends itself to ideas around the fallibility of the subject, but even more perniciously around ideas in the way in which we question whether being human matters.

We’re living in such a state of confession today that we all have to continuously atone for our sins. But the question becomes, who are the priests? Who are the ones doing the atoning? And who are the ones who have the power to do that? There’s a pernicious politics taking place in terms of a politics of shaming, which no longer allows any of us to have secrets, to have anything hidden, which is the basis of creativity. You have to have those moments of self-reflection, quiet, in isolation, before you can bring something new into the world. I find that we’re becoming technology engineers rather than creators and producers. We are all pushed into a consumer model of automation, where more and more of the human has been taken away from the scene of everything.

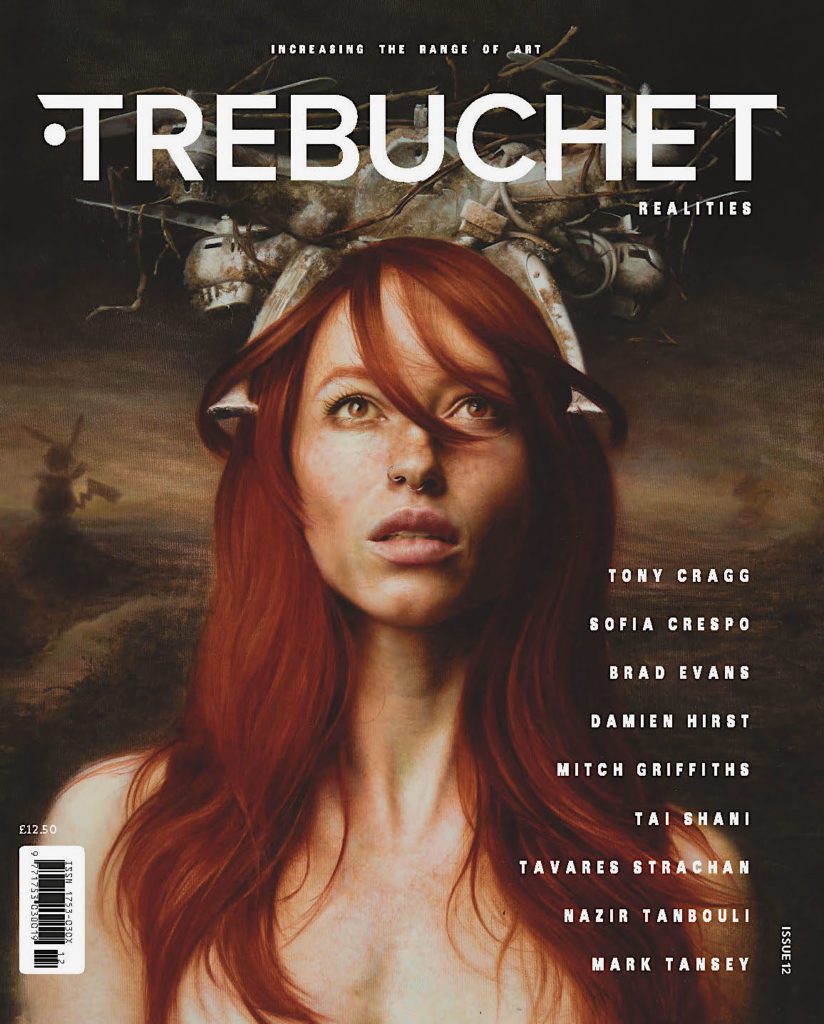

Read the full article in Trebuchet 12.

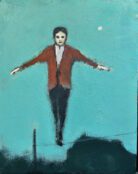

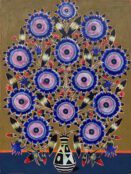

Artwork by Chantal Meza. Limited Chantal Meza prints available here.

Read more in Trebuchet 12: Realities

Tavares Strachan, Nazir Tanbouli, Sofia Crespo, Mark Tansey, Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg, Mitch Griffiths, Tai Shani, Brad Evans, Tony Cragg, Damien Hirst, and Jake & Dinos Chapman

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle