Nigerian artist and curator Jumoke Sanwo is the founder of RAI (Revolving Art Incubator), an experimental art space in Lagos, and NFT Africa. Her latest curatorial project, Untangling the Perils that Tangle Us, in collaboration with Kanbi Projects and Arts Council of England, brings together twelve artists whose practices interrogate the construct of blackness.

Here, she speaks to Millie Walton about the role of the curator, the limitations of the NFT marketplace for African artists and the Lagos art scene.

Untangling The Perils That Tangle Us is conceived as “a liminal space in history”. What does that mean exactly?

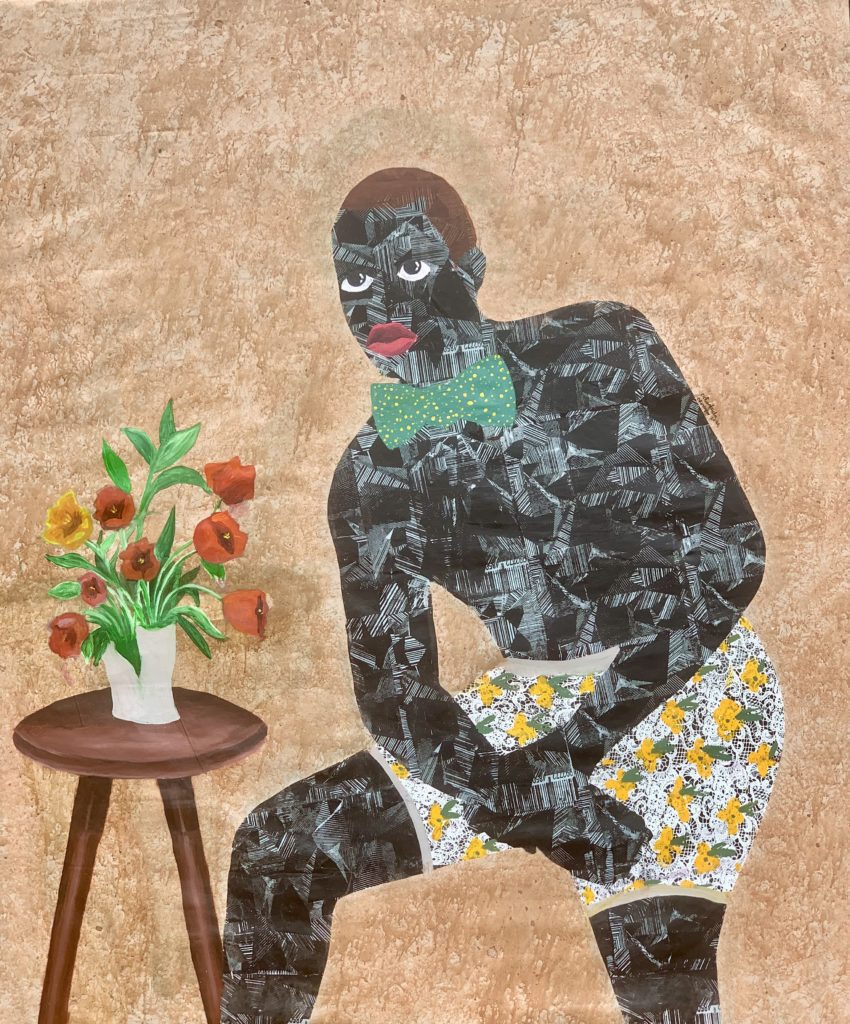

At this point in history, there’s a lot of conversation around decolonisation but there’s another conversation which is trying to engage with the construct of blackness and what that means for Africans or people of African descent who live on or off the continent. Because of the geographical complexity of that interrogation, there’s a need to have artists who are thinking beyond the construct of blackness which is not only restrictive but also bound to the construct of whiteness. So, what we have done [with the exhibition] is to present a group of artists who are looking at ways to engage with their lived experiences in a way that is more authentically tied to how they are in reality as opposed to [reinforcing] the projections of what blackness is supposed to be.

The title of the show references Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates. How did the book inspire the exhibition concept?

We took inspiration from that particular quote because it is where the author is trying to look at the entanglements that surround him. The quote felt appropriate to what we were trying to do as well which is to reach beyond and try to transcend some of those limitations.

For this show you worked alongside Adeola Arthur Ayoola of Kanbi Projects. How did you find the experience of curating collaboratively?

We conceived the idea for the exhibition at the height of COVID so we were both in different spaces: Adeola is based in the UK and I’m in Lagos so there was a geographical barrier between us. I’d actually worked with Adeola in the past as an artist because she’d curated an exhibition in 2018 called ‘Culture and Tradition’ which was also at the Koppel space. In a way, I see this show as a continuation of a similar interrogation. Adeola’s interest has always been with artists and the continent and how to give them a space in which to showcase their work and expand beyond the narrative on the continent. So, it was very interesting for us to come together to work on this project. We’re both Nigerians and we have similar backgrounds and a similar world view, which helped us in terms of structuring how we wanted it to work. We had a lot of Zoom meetings and had to do a lot of virtual studio tours with artists in the course of their production to try and understand how they were putting the work together but also to see how they were managing during the pandemic. It was also challenging working with artists from different geographical locations and knowing how to put it together but I’m happy that we’ve been able to pull it off.

How did you go about selecting the artists to include in the exhibition?

Once we’d decided on the concept, we started researching artists that were engaging with this sort of subject in their work. The artists all had to create work specifically for this exhibition but we looked extensively through their previous works.

Was it important to include a wide range of mediums?

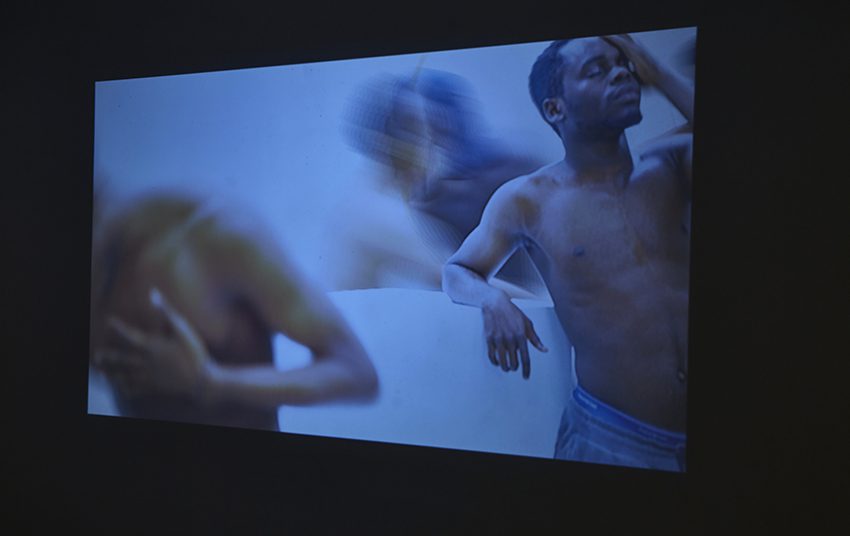

Yes, it felt important that we shifted our attention from two dimensional to begin to explore other mediums as well. So, we were started thinking in terms of sculpture, for example, because that’s a medium that is often overlooked due to portability and the fact that it’s also easier, in a way, to engage with paintings, but we were also looking at new media and exploring video art which is relatively new on the continent and you find very few artists [employing those tools].

How does your own artistic practice fit into your curatorial work?

My curatorial practice was inspired by my artistic practice. I see myself as an artist curator and I think my foray into curating was and still is a way to bridge the gap of the limitations that exist in Lagos where I live. In terms of my artistic practice, I’m interested in memory and how memory engages with spatial and temporal realities. I work across different media: photography, video art and virtual reality as well. My curatorial practice is similar: it started off as an intervention, but over time, it’s developed into engaging with artists who are experimental in their approach and are interrogating ways to decolonize memory and knowledge.

From a more general point of view, what do you see as a curator’s role or responsibility?

I think the starting point for a curator is about developing an understanding of art history and then looking at how to situate artists within that historical context. It’s also about finding ways to articulate an artist’s practice and connect them to not only the larger artistic community, but also society.

What’s your experience of the London art scene in comparison to Lagos?

I wouldn’t consider myself that experienced in the London art scene. I had the opportunity to exhibit here in 2018 and now I’m in the role of a curator, but from the little that I’ve experienced, I would say that there’s a strong international presence in London, artists come from all over the world and while Lagos is a cosmopolitan city there are limitations in terms of spaces to showcase work. There are very few galleries and museums. Also, I would say that artistic consumption is not as democratic as it is in London. That’s something that we’re also trying to work on: to take art out of elite spaces and into places where the general public can engage. A lot of the art events in Lagos are invite only, for a select few. There are also more opportunities for grants and other forms of support in London. However, there are some advantages to a space like Lagos which is still emerging in the sense that there’s still a lot to be tapped into. I think that’s what excites me about working out of Lagos: the possibilities and also discovering artists that will shape art history in the future.

How did Revolving Art Incubator (RAI) come about?

It started as an intervention. I set up RAI because I felt like there weren’t many places for experimental artists and there was no democratisation in terms of the consumption of art. I wanted to set up something that engages the limitations that exist in the art ecosystem in Lagos. So, when we started in 2016, we situated RAI in the Silverbird Galleria mall, which is the second largest mall in Lagos. It was in the fire exit so that there were no limitation in terms of opening or closing hours, people could always engage with the space even when no-one was there manning it which brings a completely different dimension to how people engage with art. There was also a sense of democratisation because we had people of all classes coming into the space, moving through it, engaging with the art and with the artists without necessarily being invited, which creates a very interesting dynamic. That was the charm of the space. The space also opened up opportunities for self-taught artists to showcase their work and to engage with other practicing artists because for galleries, they needed formal training, but here they could come and talk about technique and discover new possibilities in art and technology.

What led you to recently set up NFT Africa? And what interests you in the medium of NFTs?

NFT Africa came about very organically. I was invited to be part of a conversation, which was organised by an incubator based in Turkey who were trying to think about what the innovation of NFTs means to artists on the continent. I spoke extensively about the fact that there are so many limitations for artists on the continent in the NFT space because the entry costs are beyond what most artists on the continent can afford. Also, you can’t access some of the platforms from Africa. I started thinking about the possibility of setting up something that would create an inroad for artists, especially traditional artists, who were thinking about crossing into the digital space; a platform that would guide them through the process and support them. So, we brought together a group of collectors who are willing to support artists in the NFT space.

What’s next for you?

I think, first of all, I need a break, take a couple of days off but then I’ll just be continuing with my work. I have a couple of projects for next year. I’m currently researching a documentary which is sort of a co-production between Austria and Nigeria. We’re trying to investigate relations between Austria and Nigeria looking at the historical and contemporary meaning of fabric and fabrication. I’m also hoping to do a solo show next year because that last time I had one was in 2015 and it would be great to explore that and see if I have anything to add to what I’ve established in the past.

“Untangling the Perils that Tangle Us”, curated by Adeola Arthur Ayoola of Kanbi Projects and Jumoke Sanwo, runs until 17 December at The Koppel Project Hive, 26 Holborn Viaduct, EC1A 2AT. For more information, visit: kanbiprojects.com

Featured Image: Installation view of (L-R): Kehinde Awofeso, Reimagining the Radar (2021); Chiderah Bosah, Ada (2021); Chiderah Bosah, Ibe (2021)

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.