[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]P[/dropcap]hil Grabsky’s biographical film, Young Picasso, opens with shots of Málaga city centre, birthplace of Pablo Ruiz Picasso. A narrator tells us that in 1907, Picasso revealed to his fellow artists a painting that so shocked them, he rolled it up and it was not seen again for another 10 years. Indeed, the voice goes on to say, the painting wasn’t exhibited until 1937. It was, we are told, the painting that changed the history of modern art.

I

Picasso was born in Málaga, the son of a bourgeois painter who taught at the art school. He painted there under the influence of his father and friends, themselves painters. A few days before his tenth birthday Picasso moved north to La Coruña, where his father took a position at the school of fine art, where young Picasso was to be taught by his father whilst attending the secondary school in the same building. In La Coruña, he painted a series of portraits, which he exhibited in the Calle Mayor. They were very well received:

“These paintings, rather than being considered works of genius, should be seen as the works of a thirteen-year-old boy already showing promise.” – Malén Gual, Museu Picasso de Barcelona

It is much later, Gual tells us, in Paris, that he has absorbed into his work, the subject matter and manner of Lautrec, the colour of the impressionists and the brushwork of van Gogh. Olivier Widmaier Picasso, the painter’s grandson differs:

“To me, my grandfather, when in Paris was not looking at the past, even if he saw Renoir or Manet, this was part of history. So, it was not very important to speak about the past; but to exchange with artists about the future. He was in the process to make sure that he was an original.”

Speaking generally of Picasso’s character and of his genius, José Lebrero, Artistic Director, Museo Picasso Málaga, tells us that as a young man, Picasso was able to work in the manner of artists much older than he, but when he matured as an artist, he painted as children did. This is given as evidence of his rebellious personality and his non-conformity.

II

Picasso, the artist, was a genius. Only artists—and few of them—possess genius. At least, that is what the 18th century German philosopher, Immanual Kant wrote in his third Critique (Kant 1987).

“Even though mechanical [craft] and fine art are very different from each other, since the first is based merely on diligence and learning but the second on genius, yet there is no fine art that does not have as its essential condition something mechanical [skilful], which can be encompassed by rules and complied with, and hence has an element of academic correctness (…) Now since originality of talent is one essential component (though not the only one) of the character of genius, shallow minds believe that the best way to show that they are geniuses in first bloom is by renouncing all rules of academic constraint, believing they will cut a better figure on the back of an ill-tempered than of a training horse. Genius can only provide rich material for products of fine art; processing this material and giving it form requires a talent that is academically trained, so that it can be used in a way that can stand the test of the power of judgement.” (Kant 1987, Ak. 310)

Kant is at pains, in this section of the Critique, to explain the uniqueness of the art of genius. However, in doing this he also pays attention to the fact that immersion in the tradition of the art under view, is essential in provision of the ground in which the genius can flourish. Kant sits academic training in an art easily beside a genius’s gift for making original art.

- The Acrobat Family, 1905 (gouache on paper), Picasso, Pablo (1881-1973), Goteborgs Konstmuseum, Sweden. Bridgeman Images © Succession Picasso, DACS, London 2018

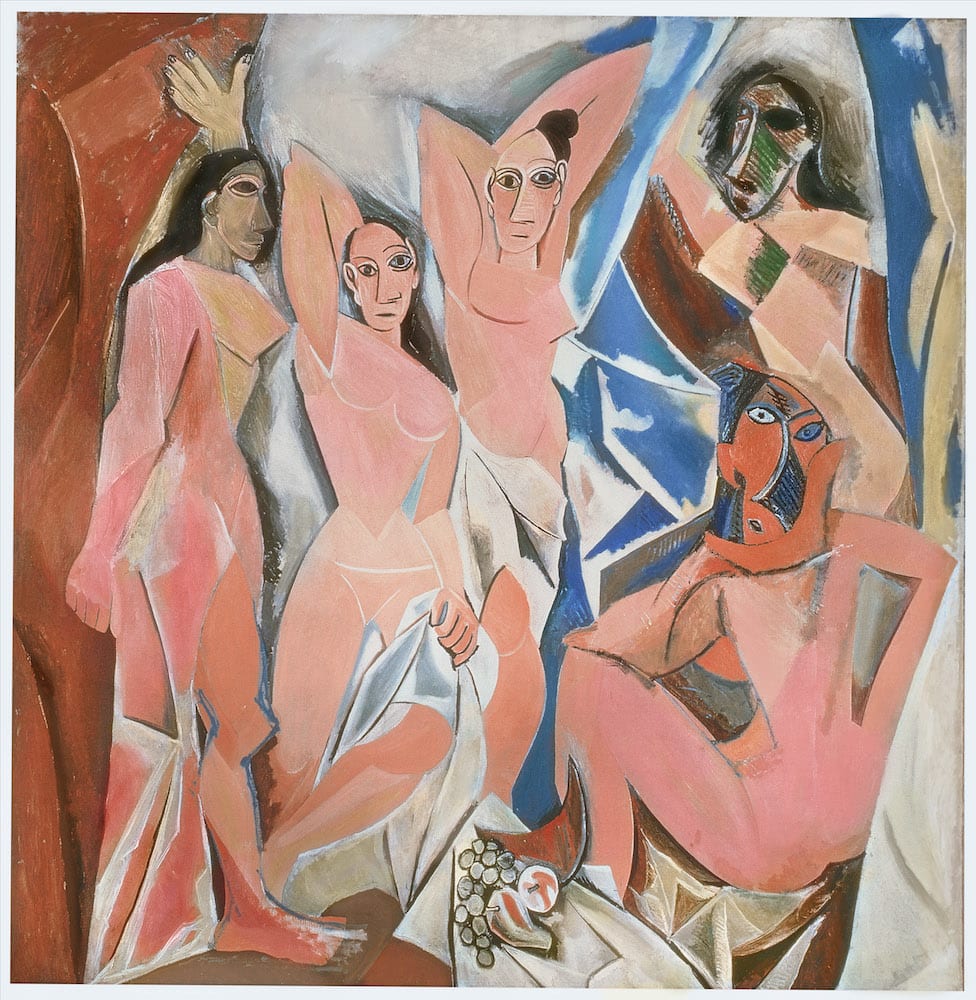

- Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,1907, oil on canvas. Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange) © Succession Picasso, DACS, London 2018

- La Vie, 1903 (oil on canvas), Picasso, Pablo (1881-1973), Cleveland Museum of Art, OH, USA. Gift of the Hanna Fund, Bridgeman Images © Succession Picasso, DACS, London 2018

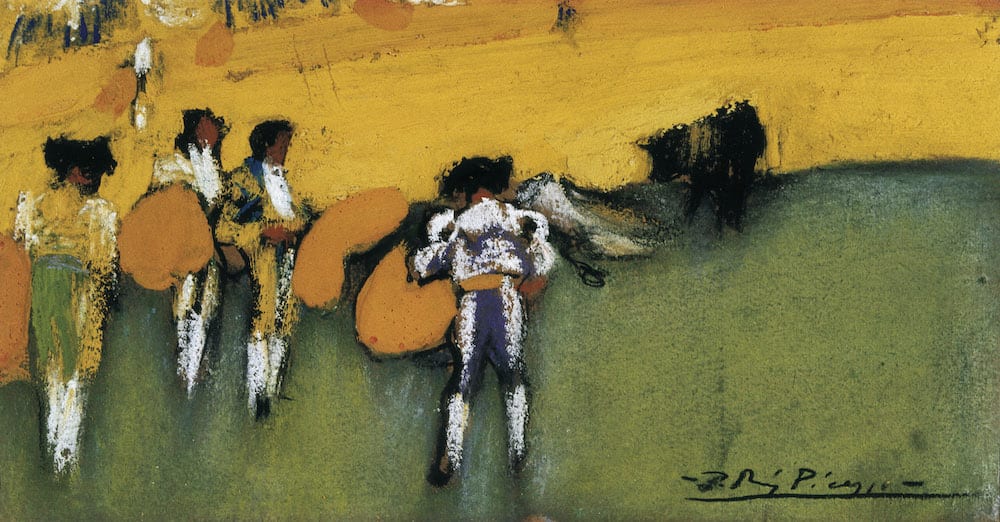

- Bullfight, 1900 (pastels), Picasso, Pablo (1881-1973), Museo del Cau Ferrat, Sitges, Barcelona, Spain, Photo © AISA. Bridgeman Images © Succession Picasso, DACS, London 2018

After the suicide of his friend, the Catalan artist Carlos Casagemas, in 1901, Picasso painted monochromatic blue paintings, most of which portrayed prostitutes, beggars and drunks. They were expressive of great melancholy. This series of paintings, the Blue Period, lasted from 1901 until 1904. Picasso left Paris, taking with him his model and partner, Fernande Olivier. The couple spent a couple of weeks with his family, before setting off for the remote Catalan Pyrenees village of Gósol. Here Picasso came across the 12th century polychromatic sculpture of the Virgin and Child. He spent his time there painting the ochre landscape and townscape of Gósol.

It is this sojourn that marks the transition to the Pink or Rose Period, which lasted into 1906 and signalled a change of atmosphere in the paintings and in the manner in which his subjects were portrayed. Now we see acrobats and circus performers as subjects, painted in a simplified more geometric form.

Back in Paris, Picasso encountered African masks at the home of Gertrude Stein; and sought out, in the Museum of Mankind, at the Paris Trocadero, thousands of objects from the colonies—especially the African masks.

“A smell of mould and neglect caught me by the throat, but I forced myself to stay; to examine these masks. All these objects that people had created with a sacred magical purpose to serve as intermediaries between them and the unknown. And then I understood what painting really meant. It’s not an aesthetic process. It’s a form of magic that interposes itself between us and the hostile universe, a means of seizing power by imposing a form on our terrors as well as on our desires. The day I understood that I found my path.” – Picasso

III

What followed the Rose Period was the painting with which the film and this review began: Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, in which we see both the influence of the Virgin of Gósol, and the African masks from the Museum of Mankind. The film rightly gives full importance to this painting. However, just as the intuitions circling with difficulties regarding tradition and originality require philosophical reflection, so too does the placement of this painting within the scheme not only of Picasso’s oeuvre but also within the scheme of modern art more generally.

In Picasso’s letter quoted above, he writes, “It’s not an aesthetic process.” The film explains early on, that his friends and fellow painters disliked the painting when they viewed it in the studio. It was described as an ugly painting.

It is not. Nor is it, according to convention, a beautiful painting. Then what? Here, we must recognise what we learn from Kant’s conception of genius. The contemporary painter is restless. In order to succeed, the painter must take upon herself the strictures of the medium and she must immerse herself in its possibilities. Only when she has mastered the medium, is she in a position to insert herself into the history she now knows from the inside.

Such a view is sketched out in T. S. Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent”. Whilst Eliot writes specifically about poetry, the structure of what he has to say about poetry as an identifiable fine art can be generalised to cover most of the other arts.

What appears to convention as ugly and unconventional will, in the hands of a genius, be transposed into an exploitation of the medium that succeeds the art of the time and supplants it with a new conception of what beauty is for an art. In proof of this, I offer Picasso’s Guernica. That masterpiece uses and integrates the technical skills developed in Demoiselles and gets us to look at an unbearable scene of the destruction of that market town.

The painting is monochrome in greys. It uses the formal vocabulary that Picasso developed after Demoiselles. It has geometric shapes that occupy much of the canvas with small vertical dark strokes that make these panels seem as if they are pages of the newspaper. Of course, in 1937, Picasso would have received most of his news concerning the Spanish Civil War through newspapers and pictorial posts. What Picasso does in Guernica is to blow up that particular mode of perception and present it as if it is cinematic. All of this he does with the means available to him developed from Demoiselles.

It is fitting that the film ends with a shot of his masterpiece, Guernica.

Exhibition On Screen’s Young Picasso is on limited release throughout the UK now

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.