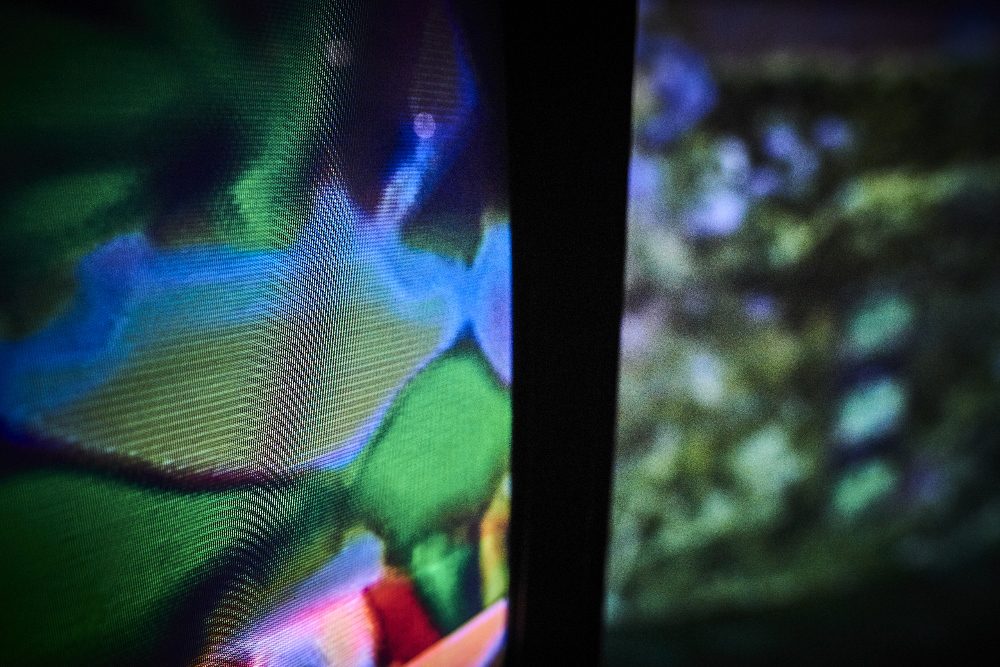

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]J[/dropcap]ames Alec Hardy’s multimedia work uses obsolete technology and plastic manifestations of the cathode age to display tribal and religious geometry, which glitches with life reflecting the dynamic interplay of life and mutation.

“Most ‘art’ is seen through some sort of screen; it gives this reduction of contemporary art. We’ve been trained to have such a high level of image literacy that we can scroll through a hundred tiny images and we lock into what we think is there.” – James Alec Hardy (2019)

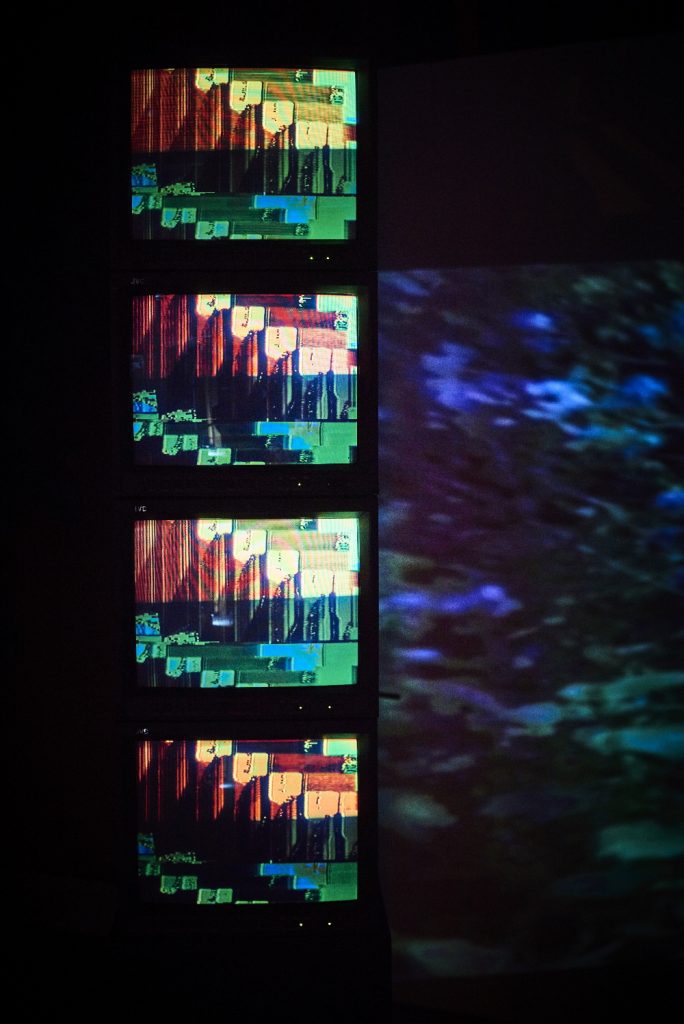

In his latest show Yggdrasil (2019) James Alec Hardy created a multilevel installation that centred around a frame of monitors, with several outlying branches of projected rooms and isolated screens. The event culminated in a sonic piece performed by Hardy where a guitar suspended in a hammock created waves of feedback as it rocked back and forth in front of a large amplifier. Hardy’s intense yet primal control of the guitar’s movement along with stained-glass images playing over surrounding monitors gave the effect of a dark sonic mass. Was it a statement of the role of the media in the capitalist rituals and circadian employment rhythms that mark our days, or something less arch but more emotional?

James Alec Hardy, Installation, Photo by Kristof Jeney

“Often described as a sardonic statement of suspicion about the digital age, Hardy’s work plays with several aspects of humanity’s celluloid other. The media representation of ideas that everyone consciously and unconsciously uses to frame their being, similar to the role the church, ritual and astrology might have held in the past. The importance of making the abstract physical and negotiable in terms of being able to move closer or further away is key to understanding his process, which might be thought of as a digital manifestation.

People refer to it as jinxing it; some people don’t like to talk about what they’re doing because then it’s unleashed on the world, but it comes back down to this question: are we capable of unique thoughts of creation, or is everything a combination of inspiration and influences? So there is this ether of ideas of consciousness which we take from; there’s this constant uploading/downloading. To start claiming unique individual authorship of that thing, it’s a bit disingenuous; how much of it is going to impact what it is you’re doing? I think of it more as the action of doing, to show that transition. […] Everything is trial and error to a degree, and there’s so little we have actual authority on in our chosen fields; the only way you learn is by failing. It’s seeing how rough it is around the edges. It’s always the edges of things that’s the exciting part.

With Yggdrasil there are these experimental elements in it, there are things I work through intuitively, they’re developed around this essential idea and column. What was key to me was to not treat it as an opening but to treat it as a launch of a work which is, like most exhibitions, temporary; they exist for a fleeting moment. That extends to, to sustain the creation of art, with a commercial wing, is a gallery going to try and stop art moving around? But then stuff’s old and gets put in storage. I always knew from the moment Kristin [Hjellegjerde] suggested I do something what it would be, and I got playful with titles. It was always based around Yggdrasil. I had dinner one night and there was quite a lot of harissa on it, and—what do you call it when Jesus appears on your burnt toast? [laughs] There was this immaculately presented fantasy art tree trunk. I took a picture and it had a working title which was ‘momentarily appeared on my dinner plate’. Kristin’s reaction was, that’s disgusting, that puts me right off my dinner. There’s a brevity of artworks of showing things of what we put together to engineer what we call an exhibition, which ultimately flattens images or moving image documentation of what that work is. The way that I have been using Instagram, I try and take pictures behind the works, to try and present images that relate to what it is. It’s essentially propaganda; this is what this is capable of presenting, rather than this is what it is.

James Alec Hardy, Installation, Photo by Kristof Jeney

Talking about states as a subject, I’ve been having auditory hallucinations, which is a good thing. I’ve been using the space to compose sounds, and I took some boundary mics and attached them. I treat it as an active space—I’m working towards a performance at the end. You’re massaging the space and sound is a physical force, it’s movement of waves in air. You can flip the states of how your brain’s operating. To create a drone, you’re trying to make things sound still and experience the present even though you know it’s moving. You can’t just flip a switch, you have to build up to it. A friend reacted quite badly and had an anxiety attack. Basically, it’s dangerous. Some people are very sensitive to sound; you can basically flip someone’s switch.

James Alec Hardy continues in print. Read more in Trebuchet 6 – Time and Space

Artist Website: jamesalechardy.com/

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle