Through a combined practice of photography, writing and weaving, Kenturah Davis unravels at the complexities and shortcomings of language and our visual experience.

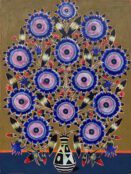

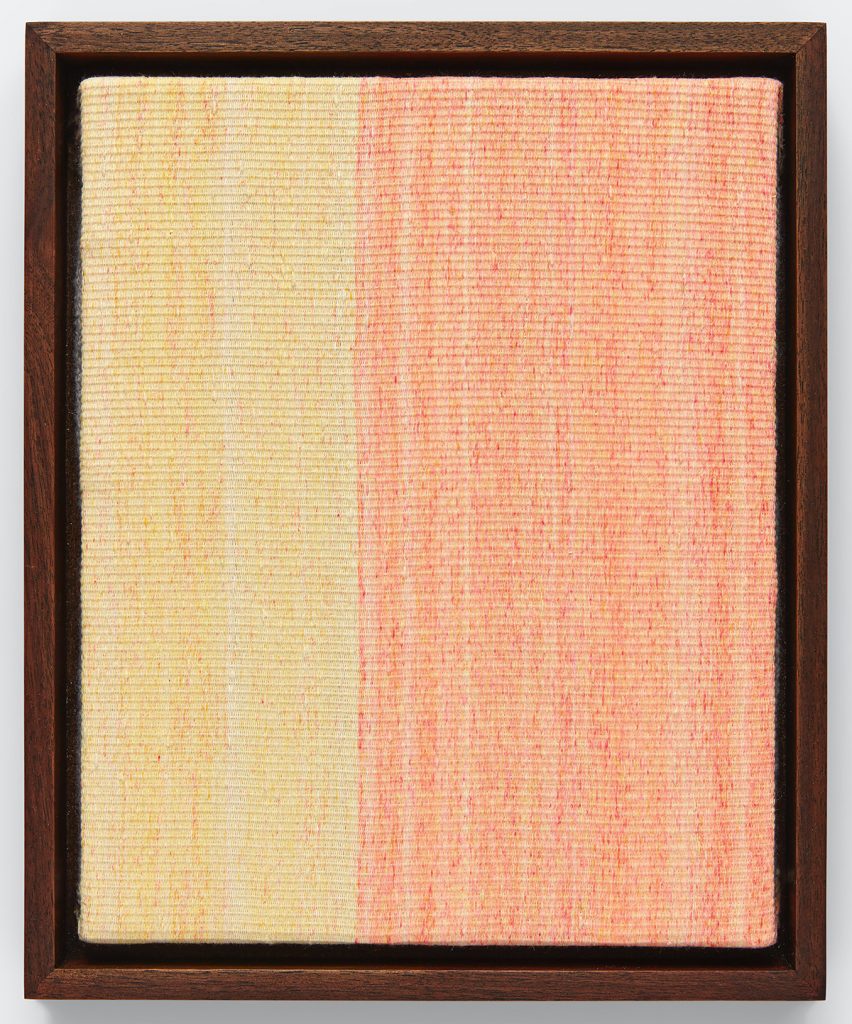

Lines of Thought at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery is the first UK exhibition of the LA-based artist’s work in which her series of ‘text drawings’ and weavings are shown alongside an installation by feminist artist Mary Kelly and works by Agnes Martin.

Here, Davis discusses the relationship between text and textile, modes of communication and art’s liminal possibilities.

Where does the creative process typically begin for you?

Two parallel activities generally guide the work that people see: writing (notes on texts I’m reading and responses developed out of those texts), and photography. I try to take photographs on a regular basis, so I have this archive of images I can look to and eventually translate into text drawings.

How did you come to incorporate the technique of shifu into your practice?

My paper supplier, who specialises in washi (Japanese papers), carries this fantastic book called Kigami and Kami-Ito: Japanese Handmade Paper and Paper Thread by Hiroko Karuno. I purchased a copy several years ago, but more recently I came across a second book that elaborated on the history and process. It mythologises the development of this process of making paper into thread by describing a time during Japan’s feudal period when spies needed to deliver a secret message across enemy territory; they wrote the message on paper, cut and twisted it into thread and wove it into cloth; once the cloth arrived to the recipient, it was unwoven and untwisted to reveal the secret message. The resonance of that story opened up so many possibilities around the connections between text and textiles, literally and metaphorically.

Around this time, I was also in grad school taking an archaeology class about the invention of writing. I wrote a paper about a hieroglyph for textile which crystallised the fact that weaving preceded writing as an invention with which one can encode information into a material.

After having lived in Ghana and being involved with the some of the textile traditions there, I was able to reconcile my interest in writing and weaving language. I began to write on the paper then transform it into thread and finally, weave it into a material where text and textile is inextricably bound. Furthermore, this process can illuminate the metaphoric implications attributed to textiles (a term like “social fabric”, for example).

What draws you to use a particular piece of text? Do you find yourself consciously searching for specific themes in your reading or is it more of an intuitive process?

I usually work through a series. I’ll identify a manner of discourse and investigate that through the text drawings. For instance, an early body of work considered the ways we can invent language and embraced the idea that the lexicon is not fixed, but rather a constantly changing source. Another series, called Euphemisms, explored the ways we can communicate in oblique ways yet still be understood.

Now, I’m constantly thinking about how the conventions of language fail us, so I’m trying to work out a kind of poetic as a bridge to liminal possibilities. I think there’s value in acknowledging what we don’t know and having an awareness about conditions that are at the edge of our perception.

Are your portraits drawn from real life or the imagination?

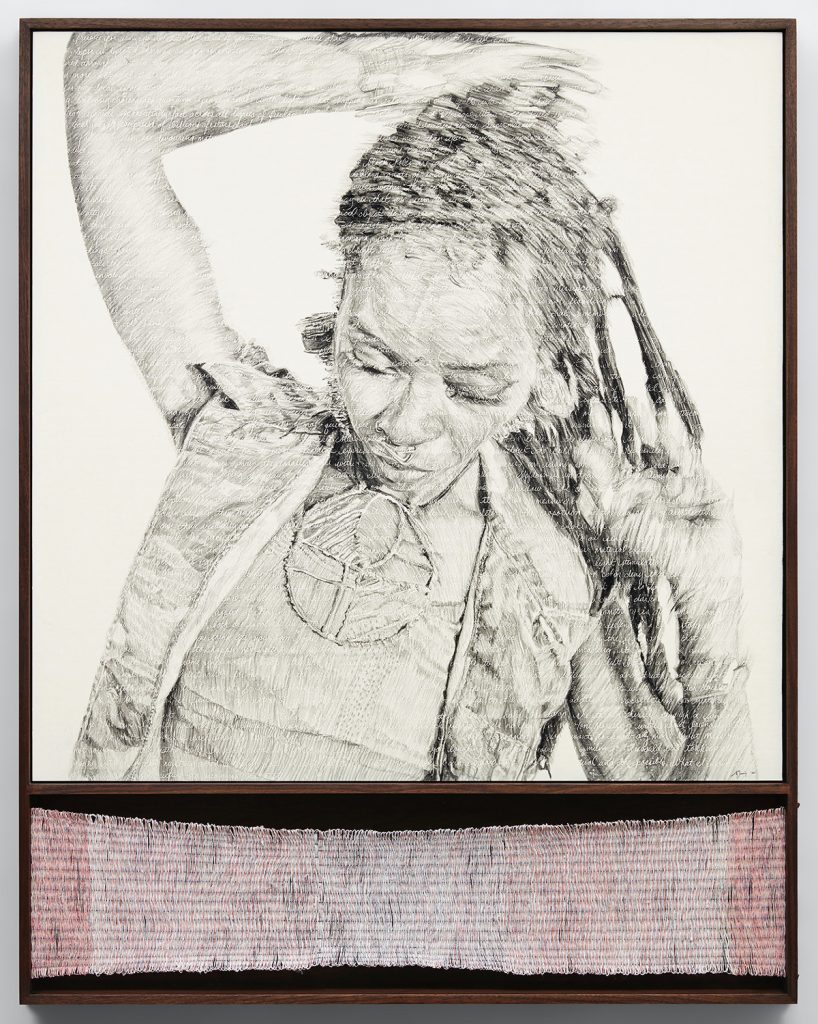

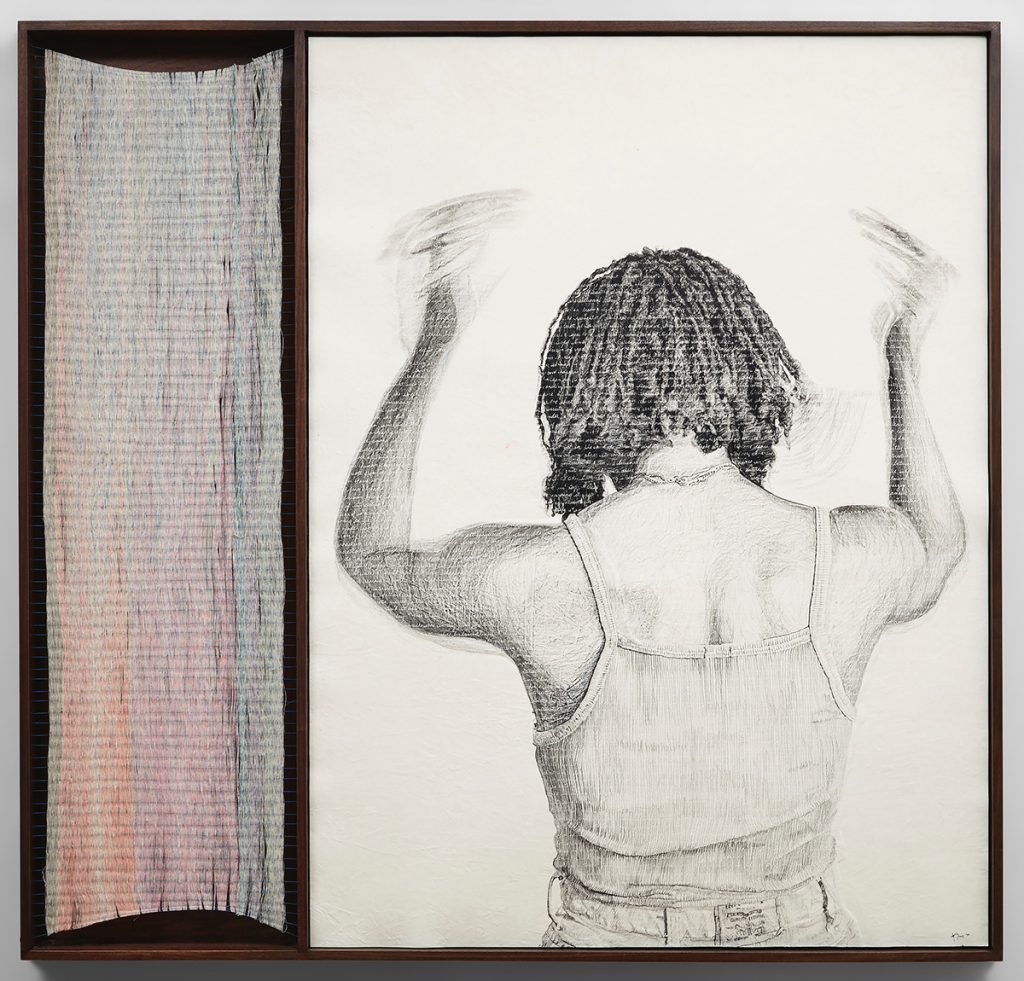

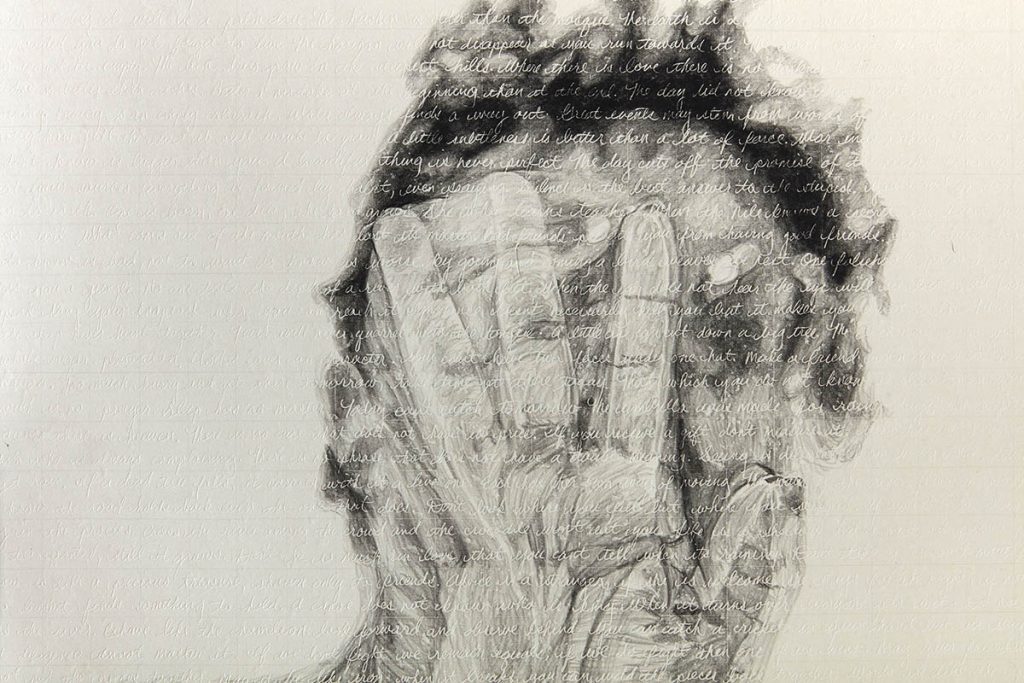

I work almost exclusively from photographs that I make. I consider the drawings to be a translation of the light and shadow information of the photograph into textual information that, in one way or another, suggests something about our relationship with language. I superimpose a grid on the image and basically use it as a map to guide me through the making of the drawing. Some drawings are rendered by stamping a text. For the most recent drawings I’ve inscribed the text with a blunt tool, so that the writing is depressed into the paper, then I do a pencil rubbing to simultaneously render the figure and make the embedded text more visible.

There’s a strong sense of movement in your work, as if your subjects are emerging or being consumed by the text. How does this relate to your ideas around identity, language and ‘the image’?

The blur and movement comes out of the photograph, as a result of making long exposures with the camera. Encountering the blurred image complicates and destabilises the language one might use to comprehend it. The text embedded in the paper works in concert with the image by proposing ideas that complicate how we understand things, like time. I’ve recently started thinking that my work is about conditions of contingency because it evades rigid categorisation. Facts that one may derive from them are contingent on one’s perspective, proximity and biases. It emphasises the fact that all the ways we might try to categorise our visual experience (including terms of race, gender, etc) don’t necessarily have to be so. Our world can be reconfigured in entirely different ways to achieve different ends.

Your portraits expose marks of erasure and the imperfections of craft – do you consider them to be palimpsests? And how does this process reflect your own attitudes to art making and your position as an artist?

I don’t try to disguise how process facilitates the results. I designed the frames for the Limen works to function as a loom. By weaving directly into the frame, I can maintain the conditions that produced it. So, seeing the warp thread grip the holes in the frame or the fraying in the threads themselves, for instance, reminds us of the structure and tension required to make it. There are other elements like embossments in the drawings that are nearly impossible to see unless you’re looking closely. The subtle shadows that they produce take the blurring of the image a step further by obscuring where the figure stops and ends. These decisions perhaps suggest that the subtle gestures in the work are as important to me as the most apparent marks. I often think about how the nature of our encounters with other people as layered experiences, so my work should be the same way.

Do you view your work as political?

I guess one could argue (or rather, many people argue) that all art is political. Given that this may be the case, I’d say all my work straddles being implicitly and explicitly political. The objective that feels most fundamental to my practice is an investigation about our relationship with the apparatus of language, which is constantly in flux. Since it imparts values and meaning, there’s a constant political edge to it.

Your current exhibition at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery positions your work in conversation with Agnes Martin and Mary Kelly. How do you see the works interacting?

I had a wonderful conversation with Mary Kelly yesterday to talk about this. The most obvious connective thread throughout the show is our use of the grid. We agreed that there’s resonance and dissonance between each of our approaches to the grid. Each of our work has evidence of the paradigm shifts of our respective generations (minimalism for Agnes Martin, conceptualism and feminism for Mary Kelly and, I suppose, identity politics for me).

From my own observations from (virtually) seeing the work together, I’m inclined to consider how each of our work diffuses hierarchy in one way or another. Martin has emptied out the grid so that there’s nothing to privilege in her drawings/prints. Kelly’s work draws equivalence between the sensory and the theoretical. She says “It’s all part of the same thing; your desire to understand yourself, and your condition as a woman in history isn’t just about the stuff of history [and] taking care of the child, it’s about the thinking.” My work integrates blur and shifting degrees of legibility that destabilises how one might perceive and assign value and draw conclusions about the work.

And finally, who or what’s inspiring you currently?

I’ve been tearing through the speculative fiction work of N.K. Jemisin. I’m late to the party, but I’m really enjoying her inventive stories and have nearly finished two of her hefty trilogies in the past couple months. Secondly, I’ve been getting into Roberto Casati’s philosophical writing about holes and shadows. Both are so ontologically complex and fascinating to think about as I try to advance ideas about perception in my own work.

Finally, there’s the music. In heavy rotation are: The Revolutionaries “Kunta Kinte – version one”; Alice Smith “Something”; Baby Rose “Over”; Tierra Whack “Feel Good”; Thundercat “How Sway”; Fela Kuti “Trouble Sleep Yanga Wake Am”, Beyoncé w/ Shatta Wale & Major Laser “Already”.

“Lines of Thought” a group exhibition featuring work by Kenturah Davis, Mary Kelly and Agnes Martin runs until 6 February 2021 at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery. The exhibition is currently available to view online via: houldsworth.co.uk/viewing-room/26-kenturah-davis-mary-kelly-agnes-martin-lines-of-thought/

All images courtesy the artist, Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London and

Matthew Brown LA. Photographs by Paul Salveson

Featured image: Kenturah Davis photographed by Xavier Fumat

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.