Paulina Olowska’s multidisciplinary practice explores representations of womanhood and female experience. While much of her work is inspired by nostalgia, her images occupy a kind of liminal space, hovering between past and present, dream and reality.

In the context of her solo show 30 Minutes Before Midnight at Simon Lee Gallery in Hong Kong, Millie Walton speaks to the artist about the concept of time, symbolism and the duality of the image.

The title of your new exhibition alludes to John Berendt’s novel Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. What drew you to this particular narrative?

There were a couple of things. The first thing was the idea of time. With this show, my intention was to point to the way we have experienced time differently because of the pandemic. On a more spiritual level, during a trip to Savannah earlier this year (where I was curating a show at the SCAD Museum of Art called Mainly for Women), I experienced a different conception of time because of the nature and the history of the place. I was drawn to [Berendt’s] novel and then to the film because the Magnolia home where the film was created was my accommodation throughout. More generally, the idea of time is often expressed in my work – thinking about the past and how nostalgia can be active in the present. The second reason [for referencing the novel] was to touch upon the notion of dreams and dream-time. In the film, Minerva, the witch, says, “30 minutes before midnight is for doing good and 30 minutes after midnight is for doing evil and I think we’re going to need a little of both tonight.” I like this concept of duality and it’s exactly what is being spoken about in the show: reacting to things that are happening in a wider sense, but also dealing with more internal experiences and the relationships between people.

Can you tell us more about how you explore nostalgia in your work?

I treat my work as a mediation of culture, especially forgotten culture or the things that have been neglected. Since our societies are always looking very much into the future or discussing the present, my idea was to look at nostalgia as a form of retrospection. In the year 2001, I moved back to Poland to review what is the nostalgia of post-Soviet architecture and post-Soviet feeling within the society. Due to many political reasons a lot of it was being dismissed, and for this reason it seemed especially important to take the point of view of a woman and think about womanhood. It felt natural for me because I had been living away from Poland and my culture, and during that time, things had changed and I was thinking about what I was missing which was a certain kind of optimism that was related to socialist ideas. Those ideas were expressed through how women were depicted in photographs and magazines. And I was thinking about how history is formed. If certain stories or myths aren’t spoken about or recorded, they seem to be lost.

One of my focuses became to raise awareness of specific neon light designs and certain fashion aspects that used to exist, and also bring attention to the community of collaborative work that was much more present in the 1960s to 70s. By bringing these kinds of nostalgic features to my work, the idea was to question whether it’s still possible to work with those methods today. When a new system comes along it often becomes the only system, and this isn’t only a problem in Poland, it’s an issue of global capitalism. Through my work, I try to address the things that we sometimes dismiss because the world is “moving forwards”.

Nostalgia is quite a complicated concept in relation to women and past inequalities. How do you address this?

It’s interesting because when undertaking research of the 1970s or speaking to my mother, the women who were really living during that time, there is a sense of romanticising the past and this is a part of nostalgia that I really like. We, as humans, can remember moments we want to keep and erase others – it’s a nice psychological process and I try to replicate that in my paintings, that process of making stories. I try to depict women not just visually, but also psychologically – I want my paintings to highlight specific ideas or narratives. The portrait of Vali Myers, for example: who was she and why she is iconic in a contemporary sense? Or somebody like Brittany Murphy: how can her portrait can talk about the pressures of womanhood and depression? Again, it comes back to this idea of duality: they are portraits of heroines, and at the same time, they reference particular subject matter and surrounding conversations.

How did you select your subjects for the portraits?

The aim was to consider the audience as if I were speaking to them and to focus on certain ideas that feel relatable, but still belong to my culture. I chose the personalities by thinking about how a painting would be read, the first impressions, and what it could represent in a wider sense. With the painting of Jodie Foster for example, Night Discontent, Day Drama, you look at the painting and firstly, see two women leaning by the car, painted in beautiful bright colours, but you begin to understand that it’s actually a reference back to the film Taxi Driver. Jodie Foster is young, she might have been less than eighteen, and in the film, she’s playing a sex worker and waiting for the night. So, what does the painting represent? Does it represent just the structure of the scene, or does it represent the drama behind it?

Also, as a result of leading student workshops and my own growing interest in astrology and alchemy, symbols and magic, I wanted to embrace the night as a productive state and drama as part of the life cycle. In the exhibition, there are images that might appear violent, but stand for something else. The portrait of Susan Sarandon, for example, is about her claiming her rights as a woman. In the work, she is being depicted by a photographer – it is an image inside an image (I’m interested in the gaze, who’s looking at who). Susan is wearing a fur coat and showing her body but between her and the photographer is a knife. This is interesting depiction of how we speak about freedom and what freedom might mean.

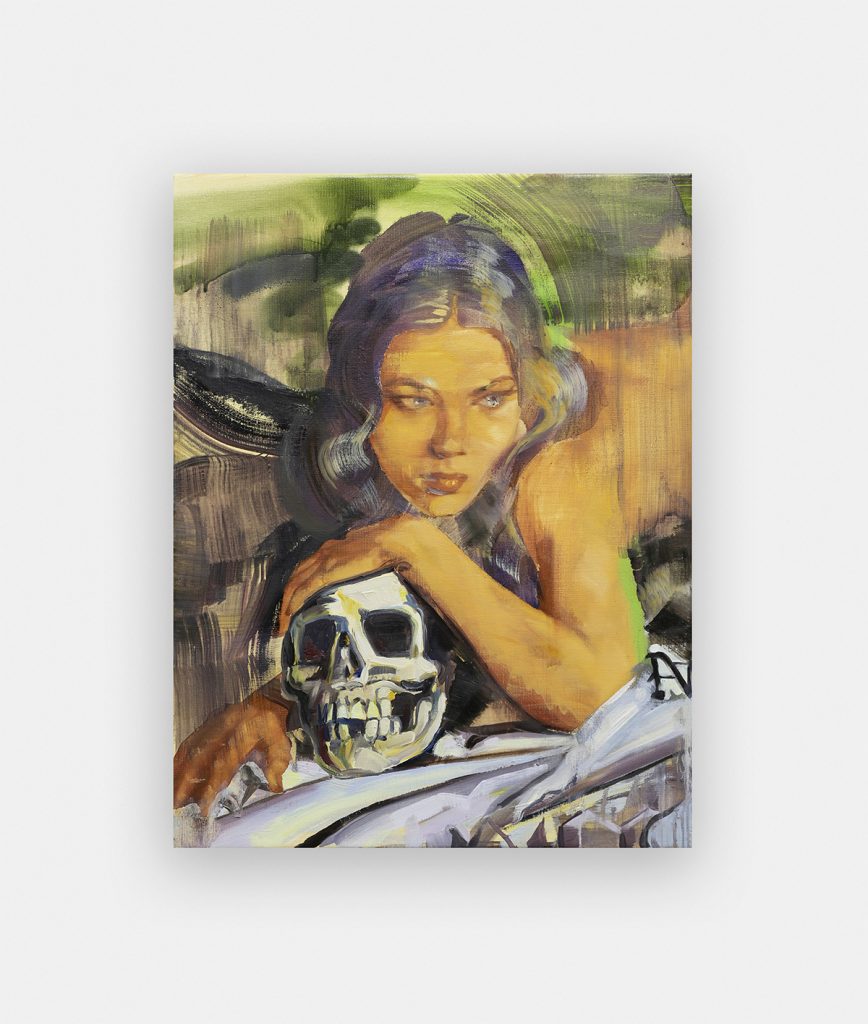

On the subject of symbols, the image of a skull often appears in your work. What does it represent for you or does it change depending on the series or painting?

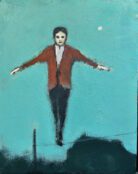

That’s a good question and to answer it we need to go into my process. In the studio, all of my images are laid out on a very large mood board, cut out or drawn images, and I meditate on them. The images are visual sketches and while I consider myself a painter, my medium is really a form of collage. Slowly, images are selected that represent a specific moment and when an image is chosen, I begin to research it. With the image of the skull, it’s an exploration into how we read certain symbols or images, and think about the language of objects. If you look through the paintings in the show, the skull is actually depicted in a very gentle or even humorous way. In the painting 30 Minutes Before Midnight, for example, the figure is leaning on the skull in the way that she would lean on a pillow.

How does painting fit into your wider artistic practice? What’s your relationship to paint as a material?

At the beginning, photography and video were my two primary mediums, but I was very eager to work with painting as it’s a very layered process and also meditative. There is a certain oneness that you get from working with paint in the sense that you start to have a relationship with an image that emerges and comes to represent you, but it is also a relationship that is sometimes frustrating, when the paintings don’t turn out right, for example.

Performance became a way to highlight the way that my interest in nostalgia is about making it alive and active. With the paintings, I couldn’t make that point as easily because, at the time, people said they looked like they were painted in the 1960s and questioned why they were relevant in 2010.

Now, both performance and painting are principal. For the last couple of years, I’ve lived in the countryside and the studio is a very intense space for experimentation. The concepts and ideas explored in my performances relate to my paintings and vice versa.

You’ve spoken before about your work being in dialogue with other artists. Are there any artists who have been particularly influential on your practice?

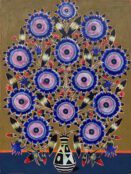

Oh, there are many! Firstly, I am so happy that in our times the practices of art and painting are opening up. There’s a much more lucid relationship with history, with gender specificity and an openness to types of art that are not academic. Self-taught artists and outsider artists are being paid more attention, which brings me so much joy.

Whenever my focus is drawn to an artist whose practice is interesting, I try to do something about it whether that’s engaging them through curatorial practice or through my own project-based work, such as the Berlin Biennale when I repainted Zofia Stryjeńska’s work in black and white and in a much larger scale in order to highlight her uniqueness in exploring folk and modernism. Another platform for collaboration with other artists is Pavilionesque, a magazine I run with different art schools and institutions. Working together with students, we review aspects of theatricality and visual culture.

What’s next for you?

I have two performances coming up. One is very related to the magazine that I just mentioned, which is called Paradoxes of Stillness. The other is a new commissioned work, which is a puppetry ballet with New York choreographer Jessie Gold. The other performance is called Naughty Nymphs in the Courtyard of the Favourites for the Art Institute of Chicago.

“Paulina Olowska: 30 Minutes Before Midnight” runs until 19 June 2021 at Simon Lee Gallery, Hong Kong. For more information, visit: simonleegallery.com/exhibitions

Featured image: Paulina Olowska, Vali The Witch of Positano, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Simon Lee Gallery.

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.