The Folkestone Triennial stands as a statement of hope against reality, making it the truest expression of art’s claim to uplift. “How lies the land” as a topic ties people with where they reside. The theme presents a statement against the idea that people form an amorphous mob inhabiting anywhere, disconnected from those around them, but instead positions them as borderless entities that recognise each other. Taking into account the differences in station and reality between artist and community, the festival sees common goals in details rather than separate specificities.

Folkestone has remained open to art and since 2008 has hosted the art triennial with enthusiasm and considerable verve. Speaking to locals, you sense that while their lives are hard, they maintain an optimistic view of art’s presence in their town. It represents another form of tourism, something they support as being ‘helpful’ if not the full panacea others might have hoped for.

The triennial operates under a team of dedicated people, led by the charming chief executive Alastair Upton and the passionate Sorcha Carey. Both led journalists around the city with an infectious sense of purpose and determination, appearing serene and assured on the sunny day we visited the show.

Their vision of the festival marries contemporary concerns with artistic flourish and remains true to the idea of ‘treating the town like a gallery’. One of the most interesting aspects of Folkestone is how artists embed their works within the town’s context. Where we expect to see artworks in the white cube of the gallery experience, here the locations and their discovery reverberate with power that imparts a sense of magical realism. The expected world redevelops into perfect settings for artistic vision. Often it takes the form of subtle language or communication; the act of walking and discovering each location assumes a potent frequency. While it remains possible to reduce each artwork by intention and execution, the overwhelming installation feeling of the triennial lingers with visitors. All artists attempted location-based work that used the symbolism of their settings to create an immanent frame for what they wanted to convey.

Monster Chetwynd’s Colourful Vision

Monster Chetwynd brings bold imagination to the triennial with her playground installation. The artist has plans for a colourful Salamander playground that conjures ‘nonsensical’ portals to a ‘surreal and other world’ that connects participants with the everyday, according to her artist statement. The installation is set to transforms a traditional seaside playground concept into something more mystical and transformative. Chetwynd’s approach embraces risk-taking in public art, creating spaces where children and adults can engage with art through play. The sculptural elements tap into contemporary conversations about accessibility and community engagement in art. While the work may initially appear as playful animal-themed installations familiar to seaside towns, this accessibility becomes part of its strength, drawing viewers into deeper engagement with questions about reality and imagination. The artist’s commitment to creating genuinely participatory art experiences demonstrates courage in pursuing artistic vision that bridges high art and popular culture.

Urgent Environmental Testimony

Taking over the old Customs House, Cooking Sections’ “Ministry of Sewers” adopts a different approach to the brief, allowing people to report on water quality. The list of issues stretches back several decades. During the triennial, people can book time to speak to an ‘official’ and share testimonies about water pollution’s effects. The UK’s issues with sewage ‘leaks’ are extensive, making water quality an issue that affects the entire ecosystem.

Reports and articles line the old Customs House walls, detailing the murky history of UK water quality. Folkestone suffered around 4,000 hours of sewage releases in 2023 alone. For a seaside town, water pollution presents an urgent issue, and by drawing this concern into artwork, Cooking Sections have created work that connects with everyone. Their piece succeeds because it touches Folkestone’s heart in ways everyone can understand, while the setup and installation maintains a serious veneer that supports the testimonial depth people feel when discussing how water pollution has affected their lives. This encompasses vectors including corporate malfeasance, climate change and government inaction – issues with wider global significance brought into local focus.

Ancient Wisdom for Modern Times

Katie Paterson’s “Afterlife” takes a different approach, reproducing nearly 200 amulets sourced from international collections of Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Viking, Islamic, Japanese, Indian, Chinese, Celtic, Greco-Roman and Pre-Columbian artefacts. The materials she uses to recreate the amulets reflect ‘endangered landscapes and fragile ecosystems’ and forces that create social entropy as much as ecological decline. Each amulet measures around 2-3cm, creating intimate fragments of civilisations and cultures that echo today but whose original makers departed long ago. An amulet contains more than aesthetics; it captures society’s soul looking forward while remaining conscious of present fears and dangers. Housed in Martello Tower 3 (East Cliff), a defensive lookout built during the French Revolutionary Wars, the interplay of history, purpose and cliffside position gives Paterson’s piece special resonance. The crumbling wartime tower allows the work to reach beyond itself.

Nuclear Legacy and Natural Cycles

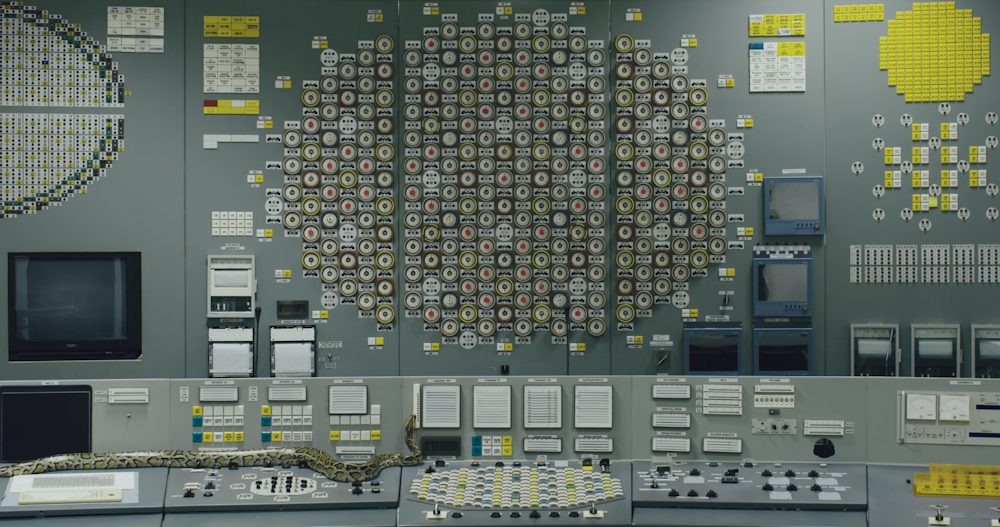

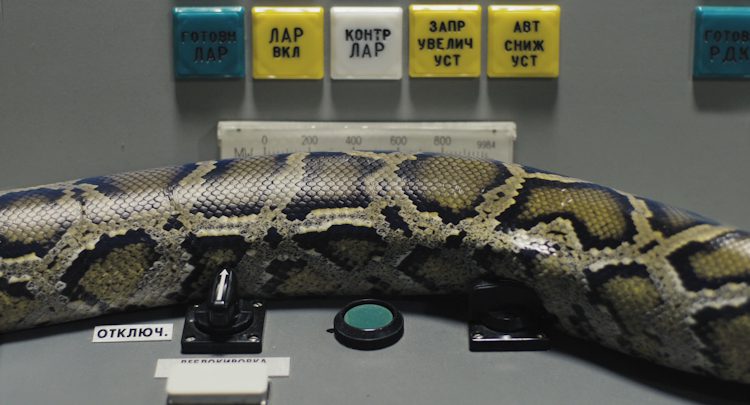

Emilija Škarnulytė’s “Burial” takes cues from Folkestone’s crumbling cliffs, which open like pages of earth’s history to reveal geological secrets and fossil remnants of life. Her cinematic work captures the slow deconstruction of Ignalina Nuclear Power Station, intercut with the sinuous movement of snakes symbolising the afterlife and the eternal. The power station was built with knowledge that radioactive byproducts would take hundreds to hundreds of thousands of years to become safe. These epoch-length consequences of our choices connect us with the future, and Škarnulytė’s work asks us to reflect on whether that connection proves positive or negative.

The scale of her work impresses, and watching workmen perform their tasks appears as the anthropomorphic representation of time itself. Starting in 2009, the dismantling and cleanup of Ignalina is scheduled to finish in 2038, when the site should become a ‘brownfield’ site suitable for housing developments. Škarnulytė’s signature approach examines borders between human systems and nature, and while parts of her piece appear elsewhere, Folkestone’s proximity to Dungeness Power Station raises questions about the price we pay for progress and the transience of those aims when placed in ecological context.

Mapping Dreams and Histories

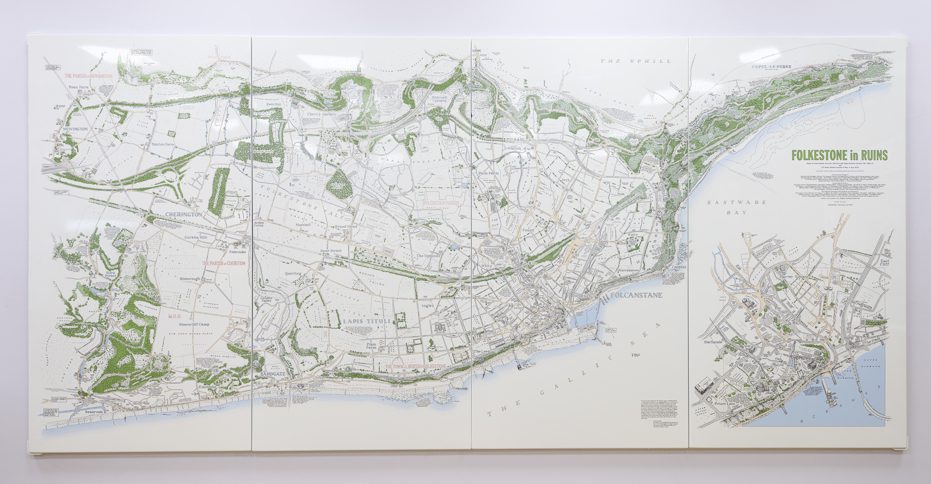

Closer to home, J. Maizlish Mole created a fantasy map of Folkestone. After researching local history, obscure maps, archaeological surveys and folklore, he spent time walking over Folkestone to create a map emphasising myths, imagined projections and layers of fabrications. “Folkestone in Ruins,” which the artist describes as a ‘profusion of pasts,’ presents itself as a tourist map at the repurposed train station at the shore.

Mole’s map presents a different view of the town, showing various dreams and pathways through the area and highlighting people’s plans. It situates Folkestone’s social life in a palimpsest of human visions across centuries. The work possesses fascinating depth and asks viewers to spend time with Folkestone itself, following social stories that create a human place. This appreciation intersects with a real community, summoning a future and creating new history through the act itself. Where the work succeeds most is in suggesting that places exist as much in collective imagination as in geographic reality, making visible the layers of story and dream that give locations their particular character.

A Town with Soul

Folkestone Triennial succeeds where other art events claim to engage with local community because here that connection proves concrete. To appreciate the art, you must find appreciation for Folkestone itself. The town reveals itself and revels in its history – social, geological and personal.

Each artist contributes to this revelation in distinct yet harmonious ways. Monster Chetwynd transforms mundane playground experiences into portals of wonder, reminding us that transformation begins with imagination and play. Cooking Sections grounds us in urgent environmental realities, proving that artistic testimony can amplify community voices often drowned out by corporate and governmental indifference. Their Ministry of Sewers transforms the old Customs House into a space where local concerns meet global crises, where individual stories become collective action.

Katie Paterson bridges vast temporal distances, connecting Folkestone’s present with civilisations spanning millennia. Emilija Škarnulytė extends this meditation into our nuclear future, where the consequences of our choices will outlast us by hundreds of thousands of years.. Maizlish Mole completes this time-based weaving by mapping not just Folkestone’s geography but its dreams, myths and forgotten histories. His fantasy cartography suggests that places exist as much in imagination as in physical space, that the stories we tell about where we live become as real as the streets we walk.

Together, these works create a portrait of Folkestone that transcends simple documentary or celebration. They reveal a town suspended between past and future, where Roman amulets and nuclear waste exist in the same temporal conversation, where children’s laughter in reimagined playgrounds mingles with testimonies of environmental damage, where local fishermen cast nets in waters threatened by sewage leaks while tourists seek postcards of an idealised coastline.

This is magical realism finding its local voice – not through escapism but through deeper engagement with place. The artists show us that Folkestone contains multitudes: it is simultaneously the pragmatic seaside town dealing with water pollution and economic hardship, and the mythical space where ancient protections still matter, where nuclear legacies stretch into unimaginable futures, where maps can chart dreams alongside roads.

To say one finds the spiritual might oversell the experience, but it remains undeniable that the town possesses soul. Through art, that soul becomes visible, tangible, and surprisingly hopeful. In a world often characterised by disconnection and transience, Folkestone Triennial offers something increasingly rare: proof that art can make us more present to where we are, more conscious of where we’ve been, and more thoughtful about where we’re going.

Folkestone Triennal 2025

How lies the land

19 Jul – 19 Oct 2025

Travel and accommodation by Creative Folkestone

Images courtesy of the artists / Creative Folkestone

Ex-London based reader of art and culture. LSE Masters Graduate. Arts and Culture writer since 1995 for Future Publishing, Conde Nast, Wig Magazine and Oyster. Specialist subjects include; media, philosophy, cultural aesthetics, contemporary art and French wine. When not searching for road-worn copies of eighteenth-century travelogues he can be found loitering in the inspirational uplands of art galleries throughout Europe.