Critically lauded in the US and perhaps something of a curator’s artist, Sietsema’s public profile remains niche in the UK. Born in 1968 he has had one-person exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Kunsthalle Basel.

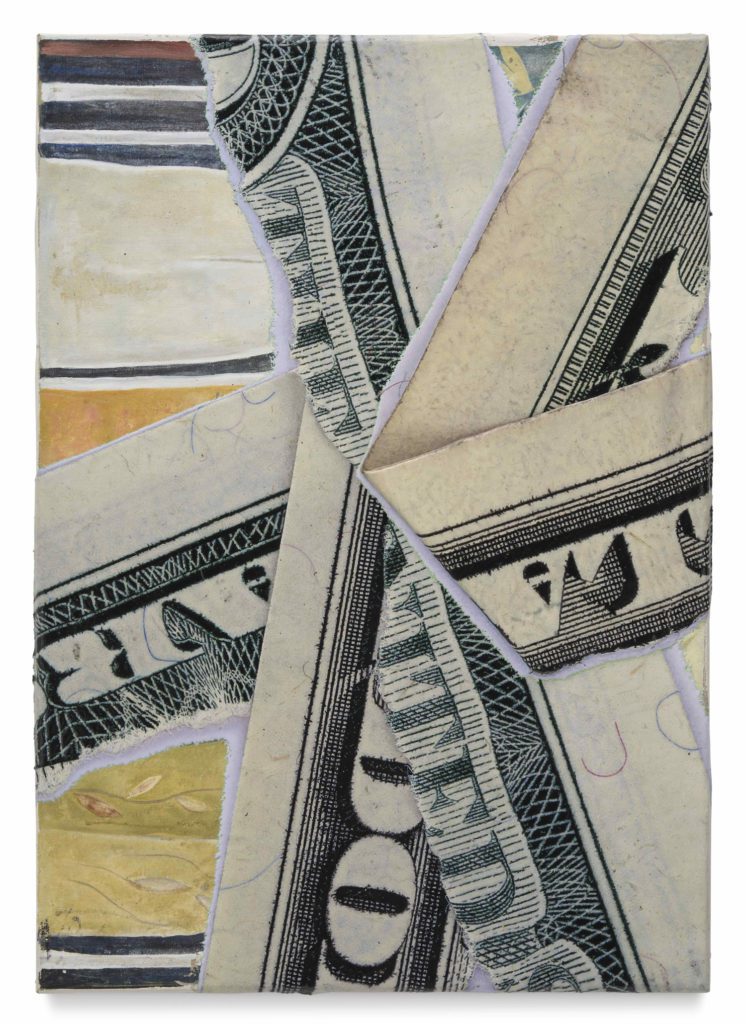

He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2005, a DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service) Fellowship in 2008, and a Wexner Center Residency Award in 2010. He lives and works in the media heartland of Los Angeles against which he feeds on the world of art rather than broader social movements (though they are tangentially related in some of Sietsema’s works) and a common current in his work is how the piece stares back at the viewer. There is an elitist judgement within his method where many pieces require a level of art knowledge to appreciate the play of meaning-construction that he’s referencing. Which doesn’t mean the work doesn’t operate without that knowledge, many of his works are accessible, maybe even more rewarding, by asking the basic question ‘what am I seeing?’

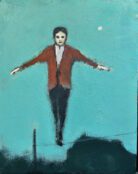

Ahead of his Paris show for Marian Goodman (12 February – 26 March 2022) Trebuchet interviewed Sietsema to discuss what processes of composition he utilised to realise old objects as symbolically aged.

Does a successful artistic process equal a successful result? And is this dangerous?

I think art has the luxury of existing in so many different forms, and along so many points of a process, and relating in so many ways to its maker that where the center of gravity is along this continuum for a particular piece changes immensely. With abstract expressionism in the last century it was all about process; splashing paint around in allegiance to the subconscious, the primal, the existential, for the most part-but of course the finished products now emanate a kind of extreme formalism and object quality that tries to make the color and composition and material primary. With the conceptual artists of the 1970s for many it was all about the idea and the physical form of the piece was to be ignored. Like the abstract expressionist works many of the conceptual artists physical productions end up also having quite a physical presence-becoming successful over time as a kind of formalism, valued for its object quality. I suppose I think the two are so closely linked that they can’t really be separated, especially in light of all the other forces acting on an artwork?

Does a successful artistic process equal a satisfying journey? And is this dangerous?

I think many artists don’t choose their processes as much as they are chosen by them-or at least it can feel that way. Whether or not the resulting train wreck or masterpiece is satisfying I guess depends on your relation to the work. In both cases the journey could be satisfying for an audience!

Do you think consciously approaching a process helps or hinders artistic growth?

Process is such a prismatically varied thing, made of up materials, ways of working, ideas, habits, aspirations perhaps. I like to think of it as a synthesiser. Like any language it naturally synthesises ideas. The thoughts must find homes even if temporary, and can be fractured or multiplied or wiped out or perhaps reflected within this system. It is perhaps a little like the story that words must wrap themselves around, or the music that instruments must scaffold. In the interaction of the two, and the necessary compatibilities and incompatibilities between the two, the story and the song change. These changes then reflect upon the next conception of a story or song and so forth. I think having some consciousness about what your process is, some intentionality, can help complicate the above described interactions productively. But of course the above also implies you have to go with the flow once the system is in motion, and I think a strong current brings the most luck.

How much of your process is borrowed? How much is developed?

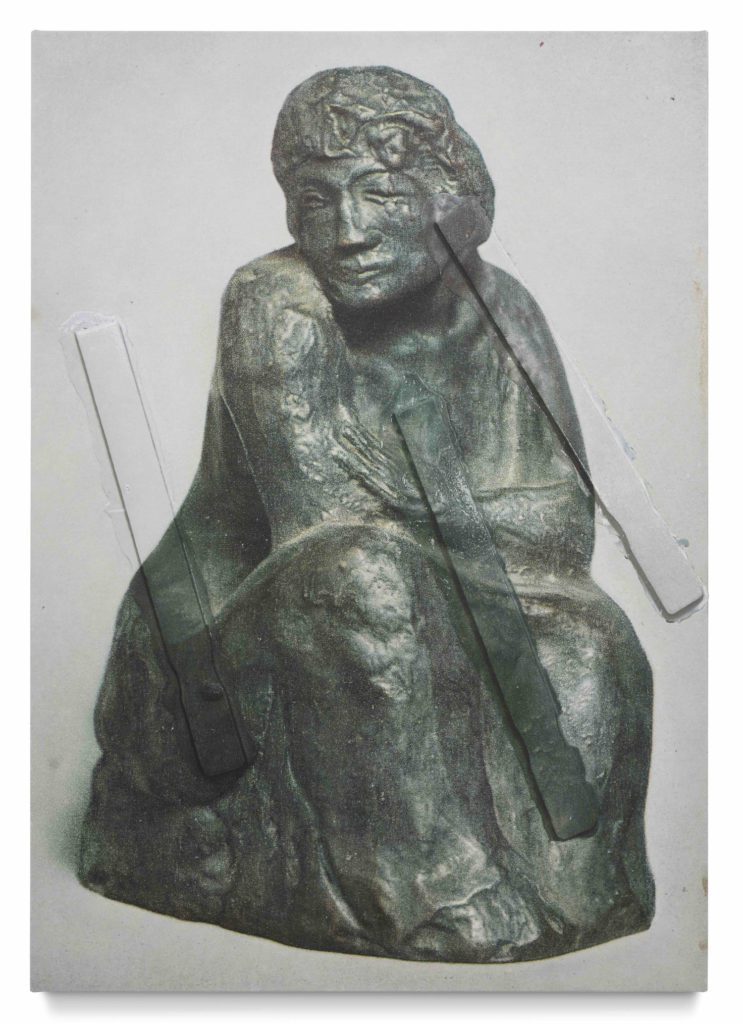

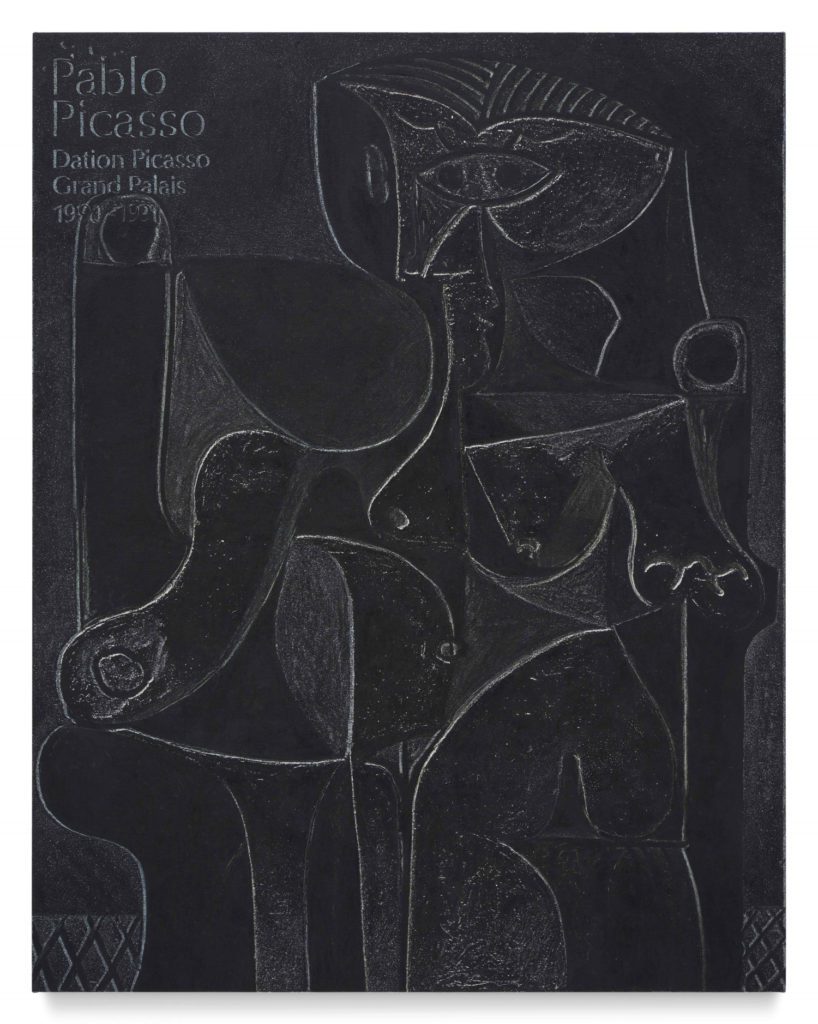

I spent a lot of time early on (1990s, 2000s) trying to force systems of chemical photography and other types of binary, concrete mechanical processes related to representation into the materiality of painting, sculpture, and filmmaking. This crossed-wires approach led me to many processes that I certainly had not encountered before. The amount of time I spent with this material/physical experimentation, around a decade, I think changed the way I do things quite a bit. For instance in the early 2000’s I was studying pre-photoshop photo retouching books I found online at used bookstores- and using the processes of hand retouching in drawings using an airbrush to make a drawing from scratch. It was a way of repairing a drawing into being, tricking myself into starting at the end even if the end was a blank sheet of paper. Prior to this time period I think I did borrow processes from artists I had worked for; casting in fiberglass and making silicone molds etc. Lots of toxic chemicals but quite fun goopy substances to play around with. And of course binary representation and copying in material three dimensional form. I think I may have let Picasso down though by not stealing any processes.

Is process more important than talent? What is talent without process?

When I was quite young, a teacher of mine was in the habit of saying talent was not important for good work. In fact he would say that talent most often gets in the way. This made a big impression on me and I suppose I’ve found it to be true mostly. I’ve seen far too many talented people implode for various reasons-with talent often comes pressure-and so many ‘untalented’ people do such incredible things. In the early 1980’s in San Francisco I was pretty deep into the punk music scene. This may have had an effect. There was very little talent, or at least what I understood to be talent at the time, but huge amounts of intensity and energy and social and aesthetic inquiry.

Can you work backwards from a piece that ‘works’ to the steps that created it? Is doing so ‘learning’ or becoming your own formula/signature/cliche?

I think there’s usually enough intuition (and it’s cousins, nephews, nieces) involved in a process that it certainly can’t be reconstructed in the same form by backtracking. Making things relies so much on the feedback loop of perception, which has phenomenological and subconscious and perhaps purely nonsensical aspects as well. Moods change while making a piece-perhaps the most important part of the process for one piece was a stomach ache. I think we’re lucky that it’s wide swings in the dark that often pay off the most.

Is process inescapable?

Like air and space and light it is nearly inescapable.

Read more in Trebuchet 11: Process

Featuring: Samuel Andreyev / Ed Atkins/ Nairy Baghramian / Phyllida Barlow / Peter Van Dyck / Oli Kellett / Tae Kim / Chris Levine / Gisela McDaniel / Paul Sietsema / Jeff Muhs

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle