Do we need a structure that spans facts and values to assert reality? And what happens if those poles are incompatible? Within the ‘culture wars’, between polarised political groups in Western Society, there is a battle to decide what is a shared social reality versus personal illusion. The stakes of this subjective political dialogue are high—being right assumes the power to demarcate the actions of others.

Unpicking the properties within this discussion is Professor Brad Evans, an academic and collaborator of artist Jake Chapman, whose work has reached a wider audience by discussing how larger contemporary mythic events (9/11, COVID, Online cultures), as methods of cultural reproduction (why ideas survive and thrive), contribute to the power of the tribal meta-cultural entities (online, interest groups, militias, political parties) framing contemporary life. Around the topic of violence ‘where humanity learns to deal with the insecure sediment of its existence’ (Evans 2017) Evans has traced a historical genealogy of sovereignty from the savage through enlightenment to where we are now, in emancipation. All are terms that require qualification amongst different logics of violence.

Speaking to Trebuchet we asked Brad Evans how he saw violence and the construction of reality.

Brad Evans: “The question of what is the “realm of the real” today is such a powerful one. In a world increasingly dominated by Metaverse-isms, the question of exactly where it is “reality”—rather than what we’re told—is striking.

Recently, I went to the Francis Bacon Man & Beast Exhibition in London, which was just phenomenal in terms of the art on show. I’ve always been struck by that Francis Bacon quote, when he says, ‘people think my paintings are violent, reality is violent, my opinions are not violent’. But the exhibition was horrific as an experience. I don’t know whether it’s just something that’s happened post-pandemic, or whether it took a Bacon exhibition to make this so explicit to me. My wife and I spent about five hours in the exhibition because there were so many brilliant Bacons that commanded your attention for so long. But what struck both of us about that exhibition was how the vast majority of people were spending only about four seconds in front of each painting, going up to it, taking a photograph, moving on to the next. It was almost as if making a personal copy has become more important than the real. This is something we know, of course, but to see it was remarkable.

Today, we have the advantages of digitalization and the dissemination of information, but also a shift towards the hyper-technological realisation of life. In many senses, Baudrillard’s work on hyperreality is telling. Where the copy is now more important than the real. It means we’re actually losing the exceptionalism of art, the ability to have an exceptional encounter with art, to be in the presence of something truly original. That, to me, was the real privilege of standing in front of all these iconic Bacon paintings. Things we’ve seen reproduced over and over in terms of imagery but which never do justice to the real; to have that unmediated experience for yourself.

I’ve written a lot about Deleuze and his ideas, and I understand, for instance, the impetus to critique the exceptionalism of the human. Key here has been to question the view that humans are at the top of the food chain. But I don’t actually think that was exceptional at all. I just think that was a normalised hierarchy. I want to insist that some humans are exceptional, that there are exceptional creative acts, that actually are non-hierarchical. At least in my estimation.

I’m struck by the ways in which there’s a peculiar take up of the ideas of imminence at work here. Deleuze is one of the most important thinkers on imminence, as far as I’m concerned. Deleuze also warns of the dangers of imminent thinking without a grounding in the history of philosophical ideas. As he famously said: you can’t become a philosopher until you reach old age. So we need imminence, but it doesn’t mean to say that a 12-year-old is going to provide the most profound philosophical text. No, what troubles me today is confronting the hyper-reality of accelerationism and the ways in which that brings and authors its own violence. One of the brilliant things which Art has done historically, and this is the one of the one of the things which I wrote about in my book, Ecce Humanitas (2021), is to see art as resistive in a poetic way. It’s not just representational. Some of the greatest artists, the greatest in a loose way, have been the ones who have been precisely transgressive witnesses to history.

They don’t just document history, they provide a vision of what humanity could become in that intermezzo point between art and lies, that disjuncture between the past, present and future and the way in which it’s been able to traverse that. But not on an axis of progressivism versus IT art. It tilts the axes between articulation and intensive depths, and that’s what brilliant art does, in the witnessing of what it’s able to do.

What we have today is just an incessant acceleration, largely enabled by technologisation, which denies us a contemplative act on violence. And actually over-exposes us to so much that we can’t separate between the realms of real violence from its actual simulacrum. Then of course, it’s easy to sympathise with the impotent as well as the ideas which got us to this place. We can all be complicit here. I wrote some 10 years ago about the importance of thinking about violence in a very disembodied way. That violence shouldn’t just be about men on battlefields, we need to account for psychological violence, we need to account for the violence of the image, and so on. The problem I can recognise even in my own work, is that these discussions may have contributed to a flattening of violence in a way where we cannot distinguish any more between somebody being physically punched, as opposed to just being assaulted on Twitter. Every identity violently polices its borders and that, to me, has always been the great attraction of abstract art, especially truly exceptional abstract art like Francis Bacon’s. What struck me about the Bacon exhibition was when they were trying to present Bacon as this homosexual artist, almost like tokenism for the identity politics of the time. In many ways, Bacon didn’t present himself in that way, and yes,his work is rife with sexual violence, but I don’t think that explicitly defines him as an artist. The brilliance of him is actually the shattering of identity, so to confine it to his sexuality seems reductive. There’s always a greater question.

One of the worrying things I found with a lot of contemporary art is the collapse back into identity, not just as a reduction but as a process of identification of bordering. Everything has to be policed, bordered, everything has to have an explicit political meaning. Not that art shouldn’t be political. All art is potentially political. But why not leave things open to interpretation as well, let alone discovery?

You walk around the Bacon exhibition and you’re left in no doubt, this guy is a homosexual and has this real commitment to that. But the legacy of his father beating him is very clear in the same sense. To make that the explicit focus collapses the work (through good intentions) into something limited, bordered, perhaps controlled.

Take microaggressions, a dominant narrative I find pervasive in universities, which connects (and enables) ideas of safe spaces and so forth. Is it liberating or limiting? It’s becoming more difficult to have genuinely open critical conversations. In terms of talking about my backstory as an academic, my early intellectual foundations were Nietzsche, Deleuze, Foucault. I was always very much taken by Foucault’s critique of truth.

He argued there’s always another truth and that there’s no such thing as a definitive and absolute proof. We are a long way from this today. The moment we collapse emotion into truth, we are lost. We see this when the spoken word becomes a truth, for instance on social media, to quickly becoming a definitive truth regarding the conscious state of anybody’s wellbeing. This is very problematic as a way of conceiving what the political might mean. And now also, it’s deeply problematic for me to think about those things in terms of people claiming emotional truth on their side. To the extent that there is no willingness to engage with the other, with the oppositional, with the intolerable, with some shadow’s position, all of which might be very disagreeable.

To me, that’s what art does. It forces us to confront alternative visions of the world and worlds which should be unsettling first, that should disrupt our ways of seeing and thinking about the life of things. And for us to be open to that. That’s part of the exceptional encounter, that we have to be open to something which actually is going to shock us. It’s going to jolt us back and make us go ‘Well, there’s something not quite right about this, something that’s not going to have an easy answer to it’.

How does this mesh with your experiences Welsh Valleys?

I grew up in a South Wales mining town. I’m actually writing a book about growing up there because I grew up not only in an isolated valley, but also very poor. I grew up in the period during the proper collapse of the mining industry, Thatcherism and the lasting decimation of the Welsh Valleys. Today they register the highest, in every single social league table of inequalities and injustice, making them one of the bleakest areas of the country. I know those towns very well and my parents still live there. At the start of the pandemic, I went back and was doing some research on three generations of unemployment on a housing estate where I grew up. I was interviewing people on this bleak estate where half the properties are knocked down, some of them are boarded up. Then I get back to the university, and we’re having this widespread debate around white privilege. The result of which was an article I wrote for The Times saying, ‘Well, what does “white privilege” mean for these communities?’ It means nothing to me but what does ‘white privilege’ mean for this third generation of unemployed kids in the south Wales Valleys? I understand why it has traction in a university setting, because most of the kids there are privileged. Okay, that’s fine, we can work with that, but why make it a universal and deeply essentializing description? Which can then so easily be absorbed into rhetoric that fails to realise what is actually limiting the potential of these people.

A key moment for me recently was when I was giving a lecture on the importance of Franz Fanon and Subcomandante Marcos, perhaps as the first person to introduce these thinkers explicitly into the curriculum at my university. I was talking about the way the neo-Zapatistas invoked a new political imaginary through the way in which they used theatricality and art as a central methodology in their narratives. But during the Q&A at the end a student asked ‘Well, what about this thing white privilege?’ My answer was that, to be honest, it’s a term for the privileged. It’s a way of the bourgeoisie placing the colonial guilt, once again, onto the backs of the global poor. So they’re (perhaps, we’re) just trying to invoke new terms and if the poor people don’t get it, then that’s their failure to understand your language. Which is the very definition of privilege as far as I’m concerned.

I had this female student, white, very privileged, very posh, make a complaint about me, because according to her intersectional analysis, I was erasing her history. That’s right. In my critique of white privilege, I was basically erasing a feminist history? How do we even rationalise this, at the level of the reality of violence? Because to me, the people who live it are on this council estate. They are living every day with the structural effects of violence, with alcoholism, drug abuse, crime, and the increased chance that they will be randomly attacked in the streets. To these people, the visible signs of structural violence are their reality. The anxiety of living every day with your parents living on meagre benefits. And then in some safe, privileged setting we’re having a conversation about what does white privilege mean?

My point for the students was that, if we want to talk about decolonization, and so on, well, then let’s have a broader conversation. You would never have had Paul Robeson going to the Welsh Valleys and using the term ‘white privilege’. Robeson connected with the miners in the Welsh Valleys. He saw them as having a shared struggle for dignity, to eat, and the connection between the history of Wales and wider colonialism. What if Wales had been a colony in line with the plantation systems in Ireland? The thing is that they’re not colour-coded in the sort of clear way that we would like to think about them today. And it’s not like these movements are unimportant, but we need a richer appreciation of history.

Which is why art is important, because it’s a reminder of the need to be far more attentive to the visual depths of history. Art always serves as such an important reminder for me in terms of saying, ‘Well, maybe things are not the way you see them, maybe there is an alternative image of the world to the one that which you hold to be true, or indeed an alternative image of the world to the one that we know is annihilating us.’ At its best, art serves to open up the complexity of identity, the complexity of belonging, the complexity of shared human relations, and also the complexity of the shared experience that humans go through, in terms of how we can navigate the seams.

What do you think of how people are engaged with political milieu in contemporary life?

This is the strange contradiction of the current times. First of all, in the age of instantaneous communication, we’ve never been more divided. We’ve never appeared more certain and yet uncertain at the same time – in terms of who we are and what we do. Also,forms of violent erasure seem to be far more prevalent. This is a claim I made in one of the last projects I was working on, about disappearance in Mexico. It’s striking when you’re in Mexico now, that there is an exponential increase in actual human disappearance over the last 15 years which coincides with the type of digitalization as a society. So, surveillance, digitalization, the increased awareness of tracking apps and all this stuff…. That coincides with the vast increase in actual human disappearance, which you wouldn’t think would be strategically or logically possible?

Sure, but coincidence is not correlation?

The contradiction is actually reinforcing. That’s the point. Once you open it up you realise that, actually, the more we survey the world, the more we map the world, the more we hyper-technologize the world, the more violence becomes possible. It’s a strange possibility in the way where it’s easy to eviscerate a life now, to eviscerate an idea., to eviscerate what we know about the historical context of art. What does permanence mean for art, does it mean the same thing as it might have before the digital age? The brilliant late philosopher and sociologist Zygmunt Bauman (1925-2017) said that we now live in a world where everything is fleeting, nothing has permanence anymore. This offers its own violence, where nothing will now stand the test of time. It’s almost like an inversion of Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son. The Son is not devouring Saturn, and incessantly eating it and devouring its own parents, and there’s something equally tragic about that.

What then is truth? Is it all relative?

First of all, in global politics there’s a sense in which the appeal of Donald Trump was in his having a simple message ‘you can be great again’. He’s the first US president in history to tell Americans they weren’t great. He says, you’re not great at the minute, but…

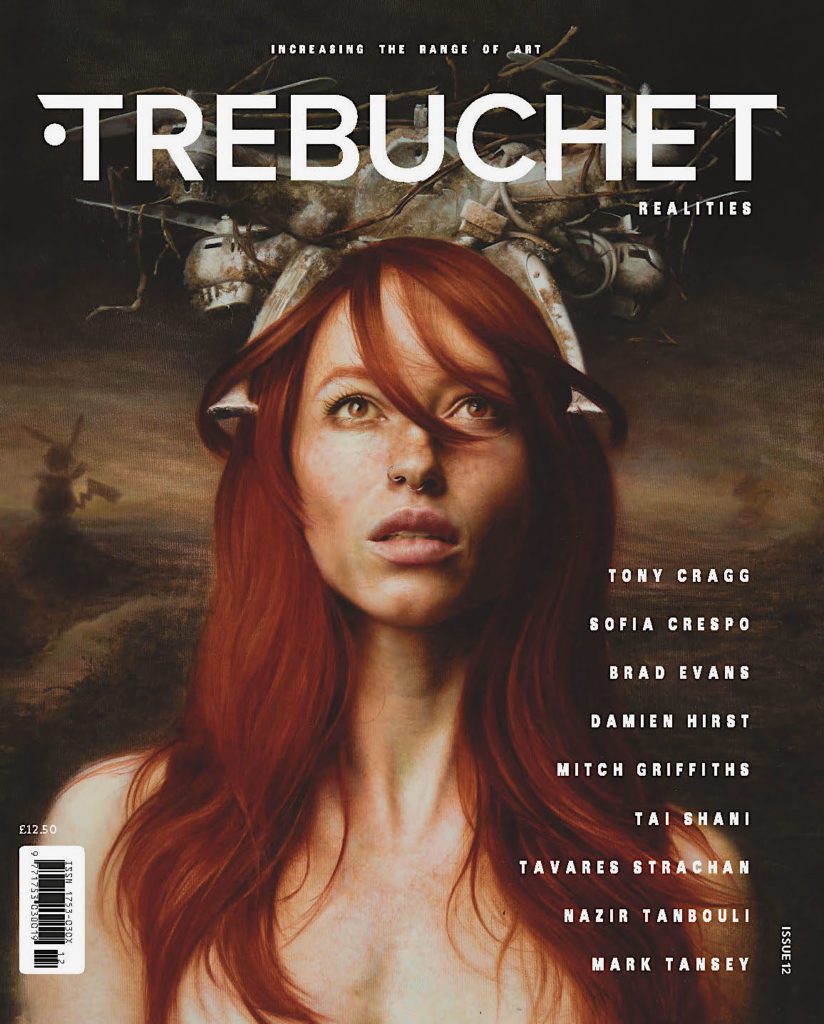

Read more next week in part two, or purchase Trebuchet 12: Realities for the full article

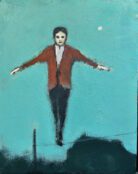

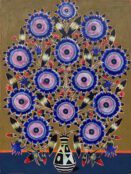

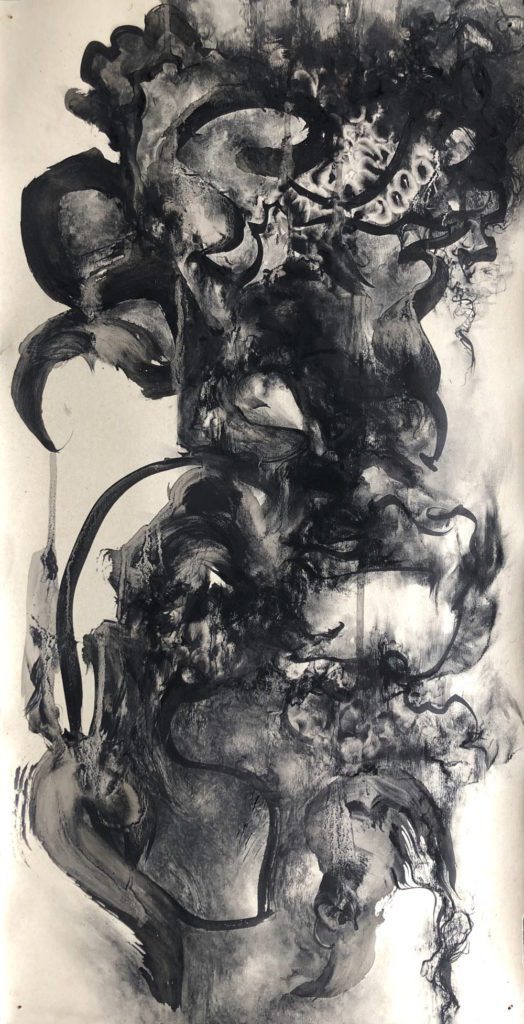

Artwork by Chantal Meza. Limited Chantal Meza prints available here.

Read more in Trebuchet 12: Realities

Tavares Strachan, Nazir Tanbouli, Sofia Crespo, Mark Tansey, Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg, Mitch Griffiths, Tai Shani, Brad Evans, Tony Cragg, Damien Hirst, and Jake & Dinos Chapman

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle