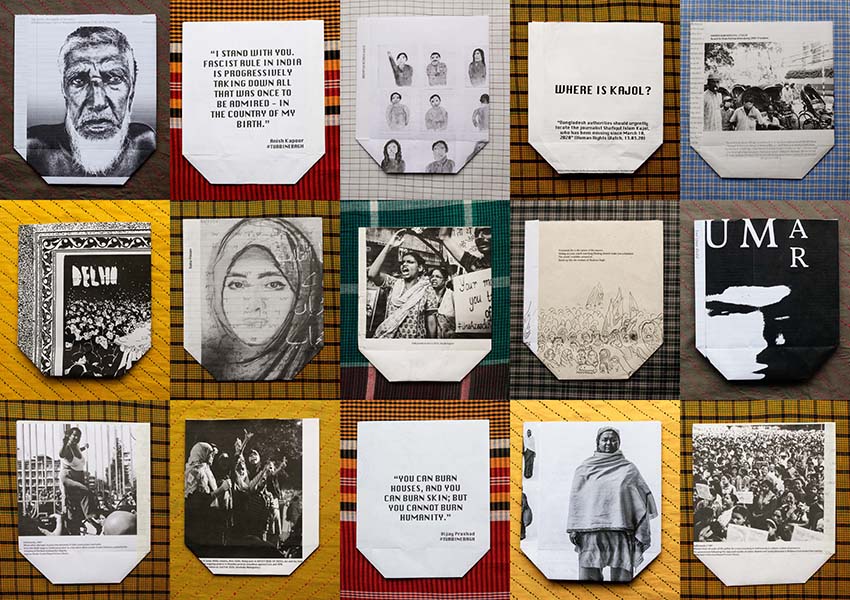

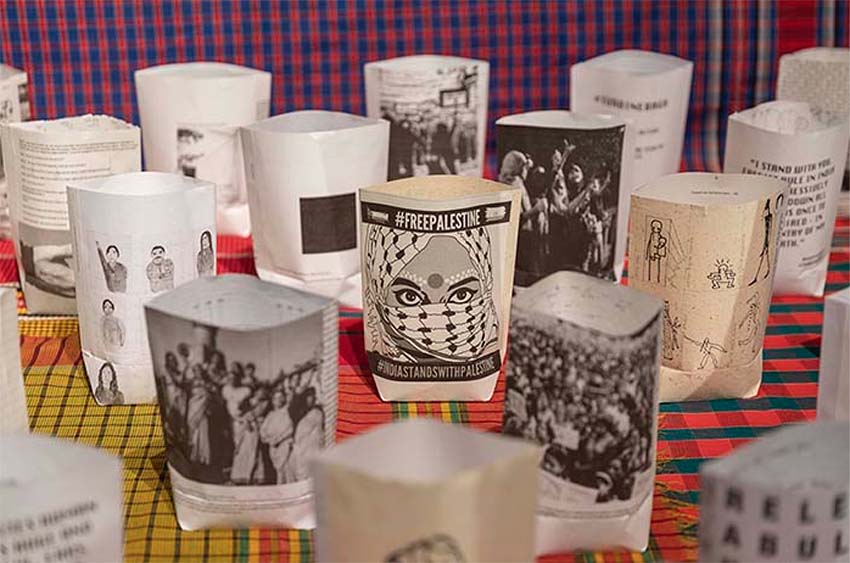

British artist, activist and architect Sofia Karim’s Turbine Bagh project invites artists, writers and thinkers from across the globe to design samosa packets expressing resistance against authoritarianism.

In the context of her nomination for the Jameel Prize and a coinciding exhibition at the V&A, she speaks to Millie Walton about her different strands of activism, the Shaheen Bagh women’s protests, and exploring architecture as medium for dissent.

How did the Turbine Bagh project start?

It happened not by design, but through circumstance. In 2018, my uncle, the photographer Shahidul Alam, was jailed by the government of Bangladesh after he reported on student protests. I was campaigning for him from London and I started to mobilise arts and culture quite strongly. As part of that campaign, I did a UK arts and culture open letter, and many important and grassroots figures signed it – people like Steve McQueen, Anish Kapoor. A friend of mine, who is a curator from Peru, called me up and said, “I just did a protest exhibition for your uncle in Lima. I have a box of photographic prints and I’m bringing them I’m in London to give to you. Maybe, you can use them in some kind of protest exhibition.” I happed to meet him at the just by the Tate Modern where Tania Bruguera had just opened her Turbine Hall commission and I’d gone to see it. He said to me, “Oh, maybe I could DM her.” I didn’t think anything of it but then, the next day, I was on the tube and I got a message from him saying, “I’m with Tania, and she says bring those prints tomorrow and you can do a protest exhibition in the Turbine Hall.”

I had no idea how I was going to put together a Turbine Hall exhibition in three hours when I had to pick up kids, do all the housework etc. All I knew is that the photographs were from a series called Crossfire that my uncle did about extra judicial killings in Bangladesh. They’d been photographed in torch light because torch light is the last light those victims would probably see: the policemen’s torch. So, I went to the pound shop and I bought a whole bunch of tiny mini torches for a quid each. The next day I turned up at the Turbine Hall and Tania was brilliant. She just said, “Do what the hell you like.” So many artists would have never let some unknown person just start doing stuff in case they got bad press or whatever, but Tania didn’t restrict me at all. She told me that she was in solidarity and that the photographs of the killings were familiar to her in terms of what they faced in Cuba.

I laid the prints on floor, each with a little torch. The text was in Bangla and I hadn’t had time to do English translation, but people were using their phones to translate the text and they were understanding it. Kids were running off with the torches, doing cartwheels all over the prints. I knew Shahidul would love that because he’s totally into that kind of anti-precious approach to art, where everyone partakes. Tania suggested that I should do it again in half time when more kids would be able to come, so we did. Then, when the India protests broke out, I thought I’m going to try and use that space again.

Why was it important for you that kids were interacting with the work?

Kids are my greatest allies as an activist. When I was campaigning from my uncle, adults started getting quite tired of it after a while. Some people were a bit cynical of the big ideas, they said “Oh, you’re never going to get him out” and suggested that I was aggravating the government by making all this noise. But kids have always supported me, they loved all the ideas that I had. They are never cynical, they think everything is possible and they don’t judge. They also come up with really good ideas of their own. Some people asked me whether my kids ever found it traumatic, but they didn’t, they found it really exciting. They came to all of the protest exhibitions and they never made me feel like a crazy person.

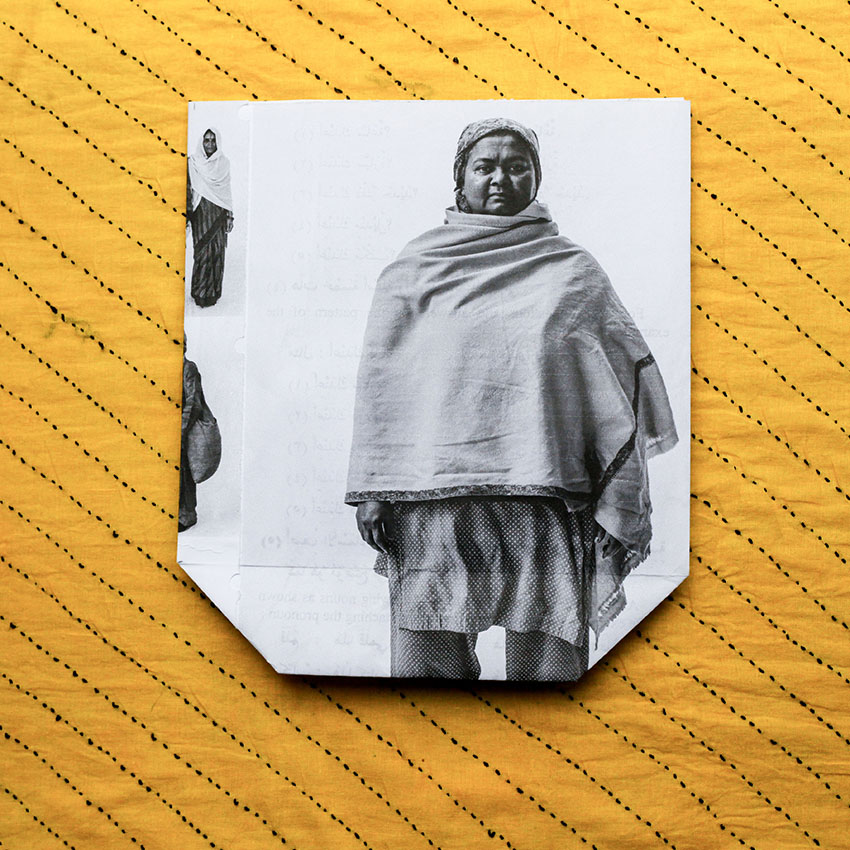

For the V&A exhibition, the [curators] decided to spotlight one packet, which I found quite surprising because it’s a really simple, basic design, very graphically plain. All it says is: “Where is Kajol?” It was made by my seven-year-old daughter during lockdown when the Bangladeshi photojournalist Kajol disappeared in Bangladesh. I was trying to do homeschooling and it was really boring so I thought I’m going to involve my kids in my work. I told my daughter about Kajol’s story and she decided she wanted to make a packet. I posted the design on Instagram and pretty soon after that we got this DM from this 20-year-old guy who said, “Kajol is my dad.” So, we began campaigning with him.

Photograph by Sofia Karim

What inspired you to use samosa packets as an artistic material?

In February 2018, before my uncle was arrested, I went to Bangladesh. I was waiting outside his picture agency and I was hungry so I bought some samosas from a street stall. Samosas always come in these little packets made from throwaway papers – a bit like how fish and chips used to be wrapped in newspaper. Anyway, this one happened to be made of throwaway court lists and I realised that in an authoritarian regime, there are so many court cases that they’re now appearing on samosa packets. So, I started to collect them from the streets – some were kids’ homework or textbooks, some were newspapers – and they began to give a portrait of the country that I found really interesting. I also just really liked them as material objects. It’s very simple paper design, but they’re actually very beautiful objects. I liked the play of light on them, their fragility, the warm texture of the paper, the smell. Anyway, I kept all of these packets – hundreds of them – and when my uncle was jailed, I took them out again and started to wonder whether his court case would ever appear on a samosa packet. Then, I started making a few packets with our version of the news reporting on what was happening to him.

Jumping forward to when the India protests were happening, I was planning this project at the Tate Modern and decided that we’d all sing the protests songs that were being sung in India at that time, but I was also thinking a lot about what format the exhibition could take. As I was seeing a lot of protest art that was being made in India and across the world, I decided to do a call out to gather artworks from writers, poets, artists and thinkers which I would then print onto the packets. My idea was to fill the packets with rice and then, stand them inside a three metre diameter circle of rice. We would stand outside that ring in a chorus and sing the songs. Some people even planned dance performances.

The samosa packet and food was also a really important part of the Shaheen Bagh women’s protests. Apparently a common greeting at the protests was, “Have you eaten anything?” So, I thought we could do the proest and send the packets back to Shaheen Bagh and other protest sites so that they would see the acts of solidarity happening all over the world.

Then, the last reason for using the packets was that it had to be cheap: I had no money. So, I was using free papers from my mum’s cupboards, leftover papers, which meant that it was also a sustainable product that talked about recycling. When you don’t have any money, you do live sustainably. The art world makes sustainability so complicated with all these really technical solutions, and this was just a really simple way to address the issue and show that in our part of the world, we’ve really always lived in this way.

What are your thoughts on social media as a tool for art and activism?

I can’t think of a civil rights or resistance movement that didn’t use art. Nowadays, “activist art” is a new buzzword and the market is commodifying it in a sense, like they commodify everything. They’ll get bored of it, maybe they already have, but we’ll carry on because as far as I’m concerned it’s not a new thing: throughout history people have protested using art whether that’s music, poetry or visual art. Likewise, social media is a tool which exists right now and an activist will use whatever tool they have to hand at that point in history. If you’re in a village where there’s no internet, for example, you’ll use song and stories. Of course, there are pros and cons to social media, but you have to navigate that and work your way around it. However, social media is just one aspect of my activism. The rest of my time is spent speaking to journalists, lawyers, human rights organisations so nothing to do with the art world or social media.

Were you always engaged in activism or did that come about after your uncle’s arrest?

I was never directly engaged with it myself, but I was always immersed in it through what my uncle and my aunt. They are really radical, progressive people and when you live with someone who lives out their principles to that degree, it shifts the way you think about and see the world. For many years though, I just had a cosy job, good salary; I followed the status quo and watched what they did. It was after his arrest that I really began to mobilise.

You trained as an architect and previously worked at Foster + Partners. How do you see your architecture practice interconnecting with your activism?

One side of my work is very public. You won’t see much of my own work if you go on the Turbine Bagh platform as I’m using that to share other’s people artworks: it’s a site for the art of the dissent and people use whatever medium they’re working with – cartoons, painting, videos, etc. But, when it comes to my own work, I’d say that my own medium for dissent is still grounded in architecture. A lot of the work that I do throughout the day is very visible and loud in a way, but when that’s all done, I think I start to process things much more internally and that then comes through my own architectural explorations. It’s quieter and more personal, and I’m really still finding my feet with that work because I previously never used architecture for dissent or to explore these new frontiers, not only of politics, but of my own emotions and my own way of being. I don’t think I’ll ever design buildings in the same way again.

Can you tell us a bit more about what’s meant by ‘Architecture of Disappearance’?

The day my uncle was abducted, I began to process things in terms of space. I don’t know if that’s because I’m an architect, but for whatever reason, I did. He was abducted, tortured and then jailed and for the first week he was put in what’s known as remand under interrogation. Anyone in Bangladesh knows that in remand you’re likely to be tortured further. When I was falling sleep during that time, I began to see space in a different way: I would try and imagine what happens to space when you’re blindfolded, as he was blindfolded. Then, he was moved to a cell called the Sunflower cell and I began to see a really strange yellow space. I realised that my whole understanding of space was already beginning to shift and I began constructing the spaces that I thought he might be in, in my mind. One of the reasons I was doing it was that I wanted to actually get in those spaces and be with him, hold his hand. So, I guess I built them in order to enter them. When I didn’t know very much, those spaces were quite formless but after he was released and I learned a bit more about the environments, I began to fill the spaces with more detail and built a series of architectural models.

It was during his incarceration, however, that I started thinking about and writing my theories around an architecture of disappearance. I began to explore architecture as a language of struggle and resistance. What I’ve realised is that other art forms have very much been used as a form of resistance – you have the poetry of dissent, music, jazz and blues – but architecture hasn’t really been used in that way historically. I don’t think it’s good enough to build say just one museum of African-American history or one Holocaust Memorial. Of course, those buildings are valid and interesting, but if you think about Nina Simone, for example, she didn’t sing just one song about slavery, jazz is an art form crafted from that crucible of pain. That’s what the architecture of disappearance is really about: trying to find a language to engage with direct action.

So, to give you an example, one of the cases I’m campaigning on currently is the BK16. BK16 are group of 16 prisoners in India: intellectuals, lawyers, poets, a Jesuit priest, quite high profile figures. I’ve started campaigning for them but I’ve also started designing 16 gardens and a pavilion for contemplation about political prisoners. I see it as a public space that anyone could visit and they might not even know it’s about political prisoners. Although architecture hasn’t been used to express struggle, resistance or human suffering as an art form, it’s one of the most potent art forms one could use to talk about suffering. There’s something about the inherent melancholy of certain architectural spaces, which I think is already to do with a connection or one’s understanding of what it is to be human and to suffer.

Why do you think architecture hasn’t been used in that way?

Well, architecture has been used to explore deeper existence and to express an underlying reality of existence. So if you think of the pyramids, they were connecting to the cosmos. Then, you have religious buildings which I think understand the visceral connection between space and emotion. Churches, for example, connect you to the suffering of Christ, but they don’t connect you to what’s happening on the street because the Emperor, or whoever is commissioning the building, most likely doesn’t want you to engage with radical action; they would rather that you fixate on the suffering of contained things.

In our current era, the spiritual interests of architecture have totally been eradicated through consumerism. They’re like adverts of buildings rather than buildings. They’re built to churn an economy, to make you go in and think about lifestyle and aspiration. Interestingly, these buildings often co-opt the spiritual aspects of architecture: you go into a luxury hotel and it’s all about Zen minimalism. So, the spiritual tradition of architecture has been recognised but it is co-opted into a luxury lifestyle product.

People often ask me what I mean by an architecture of disappearance. Does it mean that you go into a building and it invokes sensations of pain and suffering? Is it a special typology? To me, it’s not any of those things: it’s about recognising human struggle, recognising what it means to be human and attempting to move away from consumerist driven agendas.

Having worked in professional architecture for over twenty years, I can tell you that the moment I put that pen to paper, I have to be thinking about a developer’s profit, right from the outset. Every move you make is to do with maximising a developer’s profit and all the sensory, emotional, human aspects of architecture are stripped away. You’re not even asked to think about the deeper aspects of architecture.

Going back to Turbine Bagh and thinking about that project from a spatial point of view, you mentioned that you were planning to create a circle formation with the samosa packets. Is there a particular significance to that shape?

Yes, so my mum and my daughter were sitting in the kitchen making these little Bangladeshi pastries, which are circle shaped with floral designs, and that made me remember that there’s a very traditional form of Bengali art where they paint these big circular floral designs in different colours on the floor. The white one is a very popular: it’s made of rice paste and over the course of the day, the design gets washed away or removed, and then, traditionally, women paint it again. In India, a group of women had painted one of these circular floor designs and written “No CAA” inside the artwork as they were protesting anti-Muslim citizenship laws [CAA is short for the Citizenship Amendment Act, which was enacted by the Government of India on 12 December 2019]. They were arrested for writing that slogan. That’s when I decided to do a simplified version in the turbine hall with a ring of rice.

Are you still planning to do the event?

Yes, so it was postponed because of the pandemic, but all these things are driven by what the wider movement demands. At that time, the urgency of the situation in India demanded it. Something will happen again when we will all need to mobilise in a big way and will we use whatever tools we have available. If, at that time, the Turbine Hall happens to be an appropriate tool, I will go for it.

In terms of your wider practice, what does it mean to you to be nominated for the Jameel prize?

The main significance is that it’s given exposure to the cause, which is really important. Shaheen Bagh was the largest women’s resistance movement of our time and yet hardly anyone I was speaking to in the UK had heard about it. I found that interesting because Shaheen Bagh not only challenges patriarchy, but it also challenges stereotypes of the Muslim women and that includes certain strands of Western feminism, which portray the Muslim woman as backward or repressed.

There’s one samosa packet I made in response to having heard Phoebe Waller-Bridge on Women’s Hour on Radio Four. They were talking about that scene in Fleabag where she’s on her laptop in bed masturbating while watching Obama public speaking. Anyway, the hosts of the radio show asked her, “Why Obama?” And she said, “Obama represents hope and hope is sexy.” I found myself thinking about the huge amount of drone strikes that happened under Obama and yes, there were some good things that he did, but other things were hugely problematic. I thought to myself, “I wonder if the women who suffered his drone strikes, that lost husbands and children, find Obama’s hope sexy?” I got really frustrated with this statement of what I call “feminism light” and I made a samosa packet which says, “Sitting on your couch watching Fleabag isn’t feminism. Feminism light is the opiate of the masses. Stand up like the women of Shaheen Bagh.”

So, going back to your question, the Jameel prize is important because everything I’ve learned about progressive politics, about standing up and not following the status quo hasn’t come from the West, it has come from the Muslim women in my family.

What’s coming up next for you?

At the moment, I’m really trying to get my teeth into this the 16 gardens and pavilion for BK16. God knows if I’ll ever be able to get it off the ground. I also have an exhibition currently on in Boston, which includes the first drawings I began to do about the architecture of disappearance, my first attempts to express the theories in a visual language. I’ll probably continue [those explorations] for the rest of my life.

Sofia Karim’s work is currently on display at the V&A as part of the “Jamel Prize: Poetry to Politics” exhibition which runs until 28 November 2021. For more information, visit: vam.ac.uk

Featured Image: Assorted Samosa Packets from Sofia Karim’s Turbine Bagh project. Designed and made by Sofia Karim using artwork and texts from various artists and writers, 2019-ongoing. Photograph by Sofia Karim

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.