[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]wo thoughts play on my mind as I anticipate Tom De Freston’s latest solo show at Breese Little Gallery in Islington.

The first : an aversion to psychedelic sci-fi art and the second, an involuntary memory of the first time I heard the phrase ‘Charnel House’ (though I am as yet unable to recall the context of its resonance).

In light of this, the lurid colours and contorted forms beckoning from the press release images do not prophesy a portrait of optimism.

[quote]De Freston’s is a primarily

personal painterly vocabulary

of translated – rather than

quoted – cultural references.[/quote]

The first of these complexes is however allayed as I immediately encounter what only a painter can convey- the power of paint itself; in this case applied to large-scale canvasses that suck the air from the gallery space with a claustrophobic urgency to impart their desperate scenarios which verge on an unexpected beauty.

Absurdist

I have apparently entered into a theatre of cruelty and shame, acted out by strange horse-headed characters that could have apparated from the pages of Bacon’s comic book. These absurdist landscapes are conveyed with as varied an array of techniques as their subject matter : thick impasto melting into slick fluid brush strokes.

This would usually have the makings of a hasty exit and yet, the elegance with which what should be disjuncture is carried, transforms mania into intellectual freedom and casts sci-fi into the ambiguous shades of human experience. Something is at play amidst the comedy and the tragedy- it could almost be Romanticism.

‘Deposition’, Tom de Freston, 2013, oil on canvas, 200 x 150cm

‘Deposition’, Tom de Freston, 2013, oil on canvas, 200 x 150cm

Richard Cork has noted how De Freston’s work is: ‘Obsessed by images of humanity on the very edge of disintegration’.

References

This obsession is propelled into a fresh relevance in his latest body of work where scenes of water-boarding parade across the same terrain as references to Shakespeare and art historical forbears the likes of Bacon, Titian, Caravaggio and Picasso. These references are by no means secure footholds for the viewer, since De Freston’s is a primarily personal painterly vocabulary of translated – rather than quoted – cultural references.

This verbal dexterity is further evidenced in the titles of his work : Christ’s words at the crucifixion ‘They know not what they do’ becomes ‘They know what they do’; subtly shifting emphasis to initiate temporal and cultural parallels. It is not incongruous to learn that De Freston’s expansive imagination seeps into poetry too.

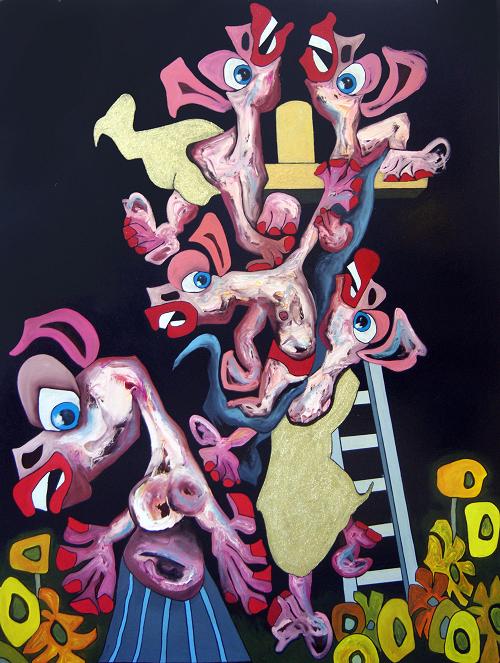

Likewise, his visual language is one of dichotomies, as stimulating as it is unnerving. Here alienation is served with an invitation to dance. Domestic settings and recognisable nods to Van Gogh’s sunflowers share the same flattened space as geometric disco balls and playful puns on ‘lightbulb’ jokes.

That familial rug is, metaphorically, pulled from under the viewer’s feet as De Freston’s juxtapositions, through painterly alignment, cast an uncanny light upon the childlike naivety of the block colouring. The time for excusable innocence is past.

‘You Can Make It Drink’, Tom de Freston, 2013, oil on canvas, 200 x 150cm

‘You Can Make It Drink’, Tom de Freston, 2013, oil on canvas, 200 x 150cm

Allegory

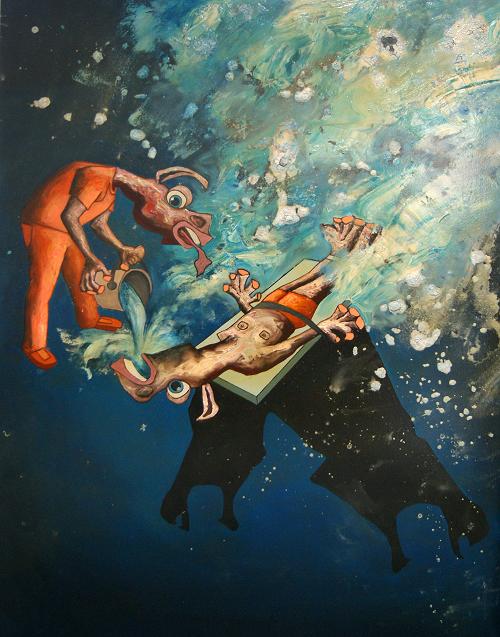

The importance of the artist’s serial approach is apparent here as a cartoonish spaceman in ‘Split’ shares the same Guantamano-orange jumpsuit as the horse-headed protagonists of ‘You can make it drink’. The relationship between tortured and torturer, indistinct within the frame itself, is further fragmented by the cross-gallery conversation – breaking the black edges of the large-scale canvasses that De Freston, with his Art-Historical background, has studied as the frames of classical allegorical paintings.

Not only this, but his conscious alignment with a theatrical background is evident in this ‘stepping out’. The super flat sections of paintwork become stage sets of a Patrick Caulfield leaning as cascades of Richter-esque clouds and spilling pools of gestural abstraction infiltrate the slickness: bearers of an impending doom.

A picture of ‘Split’, Tom de Freston, 2013, oil on canvas, 200 x 150cm

A picture of ‘Split’, Tom de Freston, 2013, oil on canvas, 200 x 150cm

This staging of the violence is what is perhaps more disconcerting than the acts themselves, since the narratives are never illustrative. Rather, De Freston is concerned with ‘moments’, of which cultural and current narratives are a jumping off point into a hallucinatory, de-contextualised parallel world that inverts our assumptions at the point of near identification.

Theatre

Painting imbues these moments with a state of flux and dramatic tension; figures suspended in the imagined three-dimensional space of the flat surface result in compositional narrative and structural devices that constantly shift our interpretations.

Likewise, theatre allows for Tragedy, Comedy and Romance to coincide within the same temporal framework. It is therefore to theatre that De Freston turns in order to find form for the horrific truths. Truths which, in society, have become as banal as the recurrent houseplant of his paintings, placed alongside adverts and celebrity gossip in newspapers and the internet.

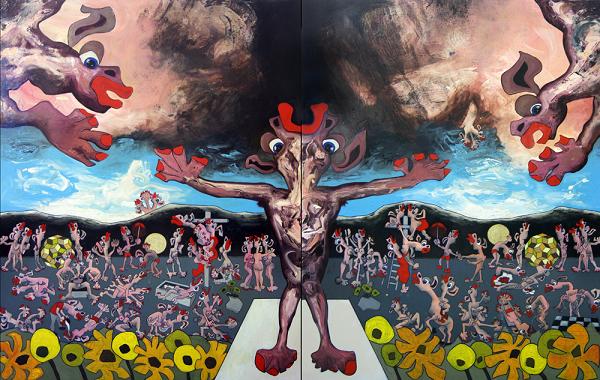

‘Last Judgement’ (Configuration A), Tom de Freston, 2013, oil on canvas, 200 x 150cm (x2 – Diptych)

‘Last Judgement’ (Configuration A), Tom de Freston, 2013, oil on canvas, 200 x 150cm (x2 – Diptych)

That his own mind works a million times faster than even his prolific output can contend with, is evident in the frantic energy with which his frenzied oil paint carries us to its pitch in the crucifixion diptych. This edifice presides as the altarpiece to, what we come to realise, is a ‘chapel’ rather than ‘salon’ hang. The medieval/modern mix gives the canvasses which strain to contain his painterly performances a cathedral-like quality.

The disillusion with convention is still manifest – though not primarily irreverent. The passage of suffering which the canvasses create does not lead to a cathartic salvation. The diptych, it transpires, can be reassembled to further upend any secure reading of either its narrative or its formal arrangement.

‘Last Judgement’ (Configuration B), Tom de Freston, 2013, oil on canvas, 200 x 150cm (x2 – Diptych)

‘Last Judgement’ (Configuration B), Tom de Freston, 2013, oil on canvas, 200 x 150cm (x2 – Diptych)

The depiction itself borrows figures from past works to create a chequerboard mapping of the artist’s imaginative connections, as horrifying as it is fascinating. As we observe newly hoofed Atlas enduring, next to what might be the Three Graces, we realise that we too have been puppeteered. Manipulated, like the biomorphic horse figures, into reading a new lexicon of violence that revolts against media sensationalism by literally out-running it through time and space.

In a moment of clarity I recall the lines from Chinua Achebe’s ‘Vultures’:

Strange

Indeed how love in other

Ways so particular

Will pick a corner

In that charnel-house

Tidy it and coil up there, perhaps

Even fall asleep- her face

Turned to the wall!

The poem continues to question whether we should celebrate that in every ‘ogre’ there is a ‘tiny glow worm’ of love, or despair that in such love there is lodged the potential for evil.

‘Crucifixion’, Tom de Freston, 2013, oil on canvas, 200 x 150cm

‘Crucifixion’, Tom de Freston, 2013, oil on canvas, 200 x 150cm

We are so often forced to think in binaries and yet, as De Freston proves, images and reality so rarely match up. Identity, morality and politics are not straightforward, nor do we truly encounter them as such, but have rather come to them that way through the oppositional alignments of modern media.

I leave feeling much as I did when I first learned that ‘Charnel House’ meant ‘House of Bones’ (sat reading Achebe’s poem in English classes) and that, through art, I have encountered a rawer depiction of existence that was yet more human and therefore, more open to possibilities.

The Charnel House is at Breese Little Gallery until 11th January 2014

[button link=”http://www.breeselittle.com/” newwindow=”yes”] Breese Little Gallery[/button]