Trace Exhibition – Patrick Tresset

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]P[/dropcap]aul’ has been described as an arm, a desk, a fairly simple robot, curious, imperfect, a medium, and perhaps ‘The Artist’.

In appearance, he’s a roughly articulated robotic armature attached to a desk holding a pen, and is controlled by a computer. Whatever wishes he’s capable of don’t come into the latest decision to stop calling him Paul. In computational terms Paul might be considered his slave name. In artistic terms Paul is the name that limits his evolution, as ‘Paul’ as defined above, is defined above. However, in human terms, the audiences of Paul’s performances really like the name ‘Paul’. Paul is someone they can empathise with and in doing so connect with a work that creates portraits of themselves. Through anthropomorphic narcissism the artist has more meaning, the medium has more meaning, the sketched portrait has more meaning and as a result the sitter has more meaning. Without ‘Paul’ the noun, there is no ‘Paul’ the artist.

Paul’s father is Brussels-based artist Patrick Tresset, whose internationally exhibited installations use computational systems that aim to introduce artistic, expressive and obsessive aspects to robots’ behaviour. These systems are influenced by research into human behaviour, more specifically how humans make marks, depict other humans, perceive artworks and relate to robots. These theatrical installations position robotic agents as actors and serve as inspiration for Tresset’s research papers in the fields of computational aesthetics, social robotics, drawing research and AI.

Through the imperfect robot called Paul (The Sketching Robot) who draws people, we are drawn into Tresset’s narrative of creation and humanity. More than simply ‘printing’, the robot is allegorically imperfect and thus artistic in the way it depicts what it is seeing. The portrait is of the artist’s modus operandi, not necessarily the subject. The didactic method the robot employs is a reflective statement on the viewer as artist of a continual portrait through which we judge ourselves via interaction and community. We are performative automata at the whim of our failing bodies. Jerky, limited, myopic, we reflect our flaws through our work, but these flaws also make our work meaningful, interesting and in the end, art.

Tresset (the man) holds an mPhil in Arts and technology, and is part of a generation of artists coming out of the computing department of Goldsmiths College (London). In 2004 Tresset joined Goldsmiths for an MSc degree in Arts Computing where, from 2009 until 2012, he co-directed the AIkon-II project, he. Since 2018 he has been an adjunct assistant professor at the University of Canberra in Australia. Trebuchet spoke to him about a premise additional to Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels claim that everything imaginable was a noun; with the synthetic creation of intelligence, everything conceivable is now a pronoun.

“Why was the robot called Paul?” I can’t remember. I think it was a marketing decision. Journalists would like it, and it would get on YouTube more. At the time, it was quite easy to get videos to go viral (sadly it’s not any more) and I used the name Paul for a long time, even for academic papers. It’s only quite recently that I’ve been trying to get rid of it. Why? I have multiple installations and the fact that I used the first name led people to think that I was always doing the same work. Which wasn’t true, so there’s a lot of reasons. But, in a certain way, I was creating self-portraits, or things representative of me, so the name Paul made sense, because of having the same initials. So, there is some personal background to it.

To give a comprehensive answer regarding a description of the robot, I’d have to speak about its behaviour, the perceptual system, and that it is something that must have actions. People often imagine robots with two legs and two arms, [which isn’t the case with my work]. The eye of the robot is this pan-and-tilt camera that moves and looks around. The planar arm is dedicated to drawings and can’t really do anything else because it only moves on one plane, and the body of the robot is an old school desk. For most of my installations this is the format I use. It has advantages because I have a basic platform that I use as a standard which I can adapt for the various installations.

Regarding the robots’ work, they are programmed for their behaviour. They react to what they see with gestures, and they follow strategies that I was using when I was a painter. In a past life I was a traditional painter who loved drawing. One of the reasons why—there are many different reasons why I switched to using computers or robots—is that as I was drawing, I was trying to be as spontaneous as possible…[Read more]

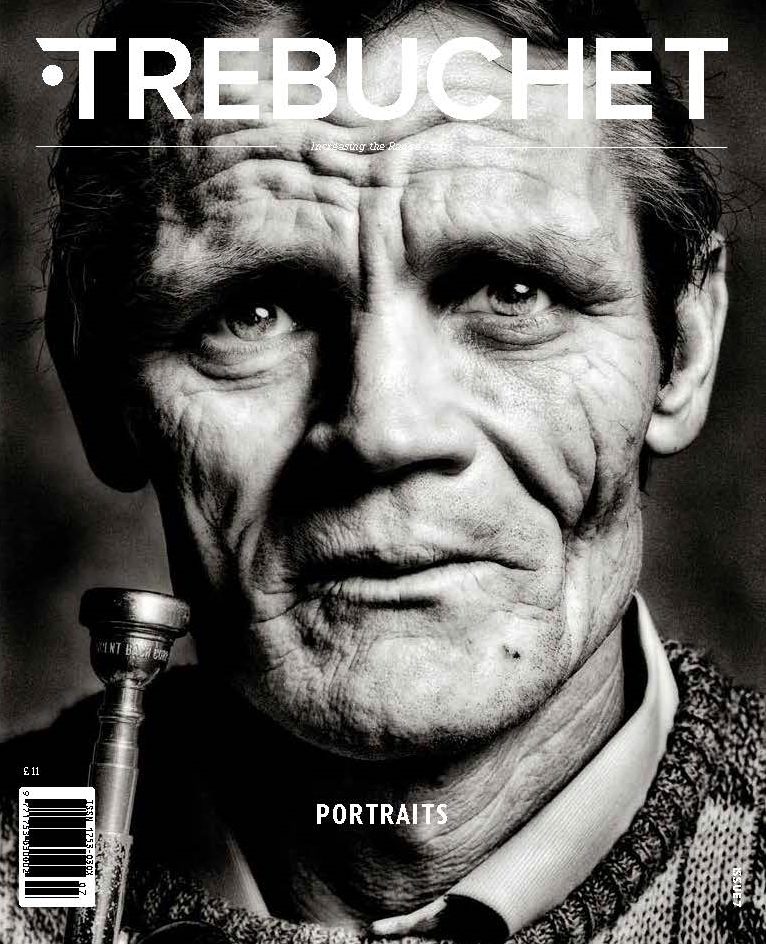

Read the full article in Trebuchet 7: Portraits

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle