Few surnames have as much historical weight as De Medici. A banking and political juggernaut this family were patrons of Botticelli, Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Raphael, and Machiavelli and their central role in the Renaissance has fueled countless books, movies, and academic treatise.

A contemporary scion of the this family is Lorenzo de Medici whose personal flair and expertise on Art has found an audience globally. Roving bon vivant Danny de Matos interviewed the resplendently European Lorenzo to discuss the role and meaning of art, then and now.

It might be unusual for Trebuchet magazine readers to see an interview with a de’ Medici because your family has a profile that could be seen as traditional and historic.

Yes, but this is a big mistake. Because first of all, there is no parallelism between the actual art and the Renaissance, because one is the consequence of the other one. The actual art is the consequence of the Renaissance. You cannot talk about art today or the last century, without knowing what happened in the Renaissance. Why is the Renaissance so important? Why do you think? Did you ask yourself, why after 600 years, the people are still talking about de’ Medici? The people learn about de’ Medici in school, in university. After 600 years, why? Because my family changed the world. Not only supporting painters, not only in the architecture, in the philosophy, it was a new start. They invented the Renaissance, and the way of life. I’ll give you an example, which you probably never thought about. Today, it’s very common that you live in an apartment in London, Paris, whatever. And you have the country house, the second house. In the Renaissance, this was a concept which did not exist. Before the Renaissance, it was a very dark period, for several reasons, but basically, due to the epidemic of the past, and the Crusade or whatever.

You’re talking about the bubonic plague.

Yes. So when we arrived to the Renaissance, the noble families used to live in the castle with the land around, and nothing else. In the big cities, people had their palaces, and nothing else. Now, de’ Medici changed this concept. They were living in the palace in the city, but they built villas outside to go to for the weekend, or to go for a short vacation, but in a distance you can reach in one day, not a very long distance. And this is all a philosophy. They don’t build any more castles. They build villa. And this is a different concept. This is one of the things de’ Medici did. When they talk about de’ Medici they talk about how they supported Michelangelo, they supported Leonardo da Vinci, etc. It’s just to fill your mouth with names. Because actually that’s not important, the importance is the revolution they did in the society and for the future of humanity, that they achieved in about 100 years. You know that the Renaissance started in Florence, and it was not casually. The Renaissance started because Cosimo de’ Medici insisted that they had the council in Florence, where they invited the Pope and the emperor of Byzantium, Constantinople, today, Istanbul. But the emperor of Byzantium came with a lot of scientists, philosophers, artists. And when they left Cosimo asked them to stay, and they created all together in Florence what is called the neoplatonisme.

Is the Renaissance period a result of Cosimo’s vision? Was he the first person to recognise the value of art and what it could do to the human spirit?

Absolutely. That was the case. But not only this, to do this, it also means that you finance those projects and those people, and that’s what he did. And this was not only Cosimo, it was his son, it was his grandson, Lorenzo the Magnificent, it was his uncle, it was all the family participating in the Renaissance. It was not a one-man show.

Can you put it in context of the family? Was there competition or obligation to do it, or was it more feeling the duty to continue? As a descendant, how do you think it was perceived in the family?

I see it as a wonderful operation of marketing from de’ Medici. You know, de’ Medici were in competition with other big families. And slowly, they sent them to exile, they eliminated all those families to sit alone in the power.

Are you saying that the patronage of art in that period was also started off by Cosimo in a very genuine way, and then did it become political?

Absolutely. It’s exactly this.

But Cosimo was genuine, because he himself wanted to be an artist and his father didn’t really allow him to.

Cosimo and Lorenzo the Magnificent, his grandson, were genuine. It started with the next generation, that it becomes political. And it becomes political because one of de’ Medici became a pope, Clement VII. Which was fighting against the fifth emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. And he created the first de’ Medici as duke of Florence. And this is the basic change of everything.

So it starts off being altruistic, a sincere thing, and it ends up in a very short amount of time within a generation being actually political. It’s about power and who we are.

Yes, exactly this.

What are the parallels between what contemporary art meant in Renaissance times, and contemporary art now?

There is no parallel because there is such a huge difference. Just between the Renaissance time, let’s put a date between 1450 and 1550. So 100 years. They were not artists, they were artisans who became artists, because de’ Medici paid their instruction. They paid their school. They helped them to become artists. And the artists of that time they draw, they build, whatever they saw with their eyes. The knowledge of that period was very small, because the world was Europe. I mean, America did not exist by the term, Asia was far away, and Europe was the world.

They only had the materials that were genuinely local to them.

Yes, but you have to think. At the time, they had to use the material they knew, which was available around them. Today, with globalisation, with Internet, we are going all over the world in the same time, we are going much faster. And you can discover easily materials that maybe you don’t know about them, but being on the Internet you can discover lots of things that you are not aware of. And it’s easier for an artist of today to find something to have a genius idea, because of this enormous availability that you have around yourself.

Using Renaissance art as just an example, if they were from Sienna, they were probably using materials mostly from Sienna, which would affect the hues of the colours, would affect the frequency of their production, all that kind of stuff. Now, production is so much easier.

Yes. And different. There is a variety of products that wasn’t there at that time. So plastic did not exist. Metals did not exist.

Do you think that now, the art that we make reflects our lives and the artists’ lives less, because they are grabbing things from outside of their own experience?

No, I don’t think so. I think every piece of art by itself is valued, not only for the artist who made it, but for the person who appreciates it.

So you don’t think it’s important that an artist works with material outside of his own geographic location, his own experience, his own possible technology? There’s a difference between what artists were making then within their own grasp, and some artists made their own colours, etc.

Yes, like Leonardo da Vinci, he made his own colour and they were actually worse than the other ones they used at the time, because we have seen that his painting did not last as much as the other ones.

So you would say that he would have made better works if he’d accepted materials outside of his geographic location.

Absolutely. Which brings to me this thinking. When I look for example at Trebuchet magazine and I see a different piece of art, you have the feeling that when the artist is showing his art he’s trying to be original, to be eccentric. And that’s a different point. At that time, they tried to show you how good you are to paint the face of this one, or to build the cupola of the dome. Which is totally different. Today, I have the feeling it’s to be noticed, to help make the difference with another artist, you have to do something very original, very different.

Is it less valid now than it was then?

No, I think when an artist is working with his mind to create something it is as much valid now as in the past. Whatever is the result. What is important is the value of the artist.

How do we value that artist? Are artists valued more when they’re not here? And is that because their output disappears so it goes up in value? Somebody like a Banksy, how does a de’ Medici look at a Banksy today? And if it were within your power to somehow create new Banksys, would you do that, or do you think that he’s a one-off? How do you view art like that?

That’s a separate question here. I think that basically if you make a step back and you oversee the situation, nothing has changed since the Renaissance. It’s again an operation of marketing. Why is one painter more valuable than the other one; it’s an operation of marketing. And if great galleries or merchants tell you this painting the value is hundred thousand dollars, you believe him because he is an expert. But actually, it may be the value could be $3,000. It’s an operation of marketing. I used to be a friend of Leo Castelli. He was the biggest merchant in the world, in the sense that he helped to create big, big artists. He invited me one night, and he was in the gallery and he had this huge painting from an Italian guy, which I never heard in my life. And the painting was something like six or seven metres large, with wood inside and the height was maybe one and a half metres. And he said, don’t you think it’s wonderful? And I was looking at this and I said, for me, it’s a piece of shit, actually. But I don’t understand the art as he understands the art. So is his valuation more valuable, or is mine? It’s difficult to say. You think he is a professional of art, so he must have seen hundreds of thousands of pieces of art, and they gave him the knowledge of saying what he says. My opinion is the opinion of anybody who walks in a museum or walks in a gallery, and you like it or you don’t. You don’t go further than this. Now, if you want to pay $100,000 or million dollar for a piece of art, you have to really like it, but again I think you pay this price because you like it, not because the value is one million dollars.

Your name means to a lot of people in the art world means patronage. And patronage of the arts. And you’ve written plenty of books about the whole family, which have included a lot of factual, historical and family facts of your family of patronage. What do you think of patronage then, as it compares to now?

Well, the culture is very different. I don’t think I have a very clear idea of how it is. It’s my opinion. In the 15th, 16th century, the patronage was to help people to discover themselves, paying for the studies, the living, and especially buying their works so they can live off of it. That was the real patronage of the time. Today, as far as I know, there is no such patronage. Everybody says, the big banks have foundations, but it’s not true. Actually what they do is an investment. They buy pieces of art for their collection to have value in their foundation. I don’t know any bank who pays young artists a salary every month, or buys their work just to develop them as an artist. I don’t know if this exists today. When they buy pieces it’s for their own gallery and they give the value that they want. And then if you talk about private people, Rockefeller or whatever, they buy pieces of art, it’s not a mécène, it’s somebody who is preoccupied with his own fortune and he thinks this is good value, and better yet it will have a more value in 20 years.

Do you think there is a more cynical approach now? When Cosimo was investing in people, was it more sincere then, than it is now? Because the motives now from what you’re saying, your belief is, that the things now are a lot more cynical, there’s a profit motive. So it’s not about the art or the artist, it’s actually about, this is the guy we can bet on.

I agree. It’s not a question of art passion. If you talk about the past, what my family did, they actually invented the mecene, the mecenasco. They invented because they started to do it. And very few people did it at the time. Today, if you Google Medici, they tell you mecene, or if you google the word mecene, they tell you Medici, so that’s why it remains in the culture, it’s one word for the other one, it’s the same one. Today, it’s a huge marketing operation. And it’s just a question of benefits, because you will never see a foundation from a bank — I say the bank, it could be any foundation for any people — go in the street and buy a painting off somebody who is painting on the street.

This is ironic, because we’re talking about one of the most influential banking families of all time. Who you yourself have said, starts off with Cosimo I being extremely sincere and his brother Lorenzo, as patronising art, helping the creation for, as it turns out, humanity. But the generations after that were doing it for political reasons, which could be translated into marketing reasons for the Medicis. How do you feel about that?

When they changed the status from bankers and beneficiary, mecene, into aristocrats and governors of countries, there was an election. A very interesting election. One of the people, I’m talking about 1742, called Anna Maria Luisa, she inherited all the 300 years collection of Lorenzo Magnifico, Cosimo de’ Medici, all the collection of the older members of the family, and that in her hands.

What artists did she have in that collection?

They had everything, they had Etruscan statues, lots of Roman stuff. They had all the money, the gold and money pieces, which have been made in the Greek time. All the artists of the 16th century. They had a huge collection. For example, all the drawings from Michelangelo. She had all the paintings and she decided that she was alone, she was the last of the line, and she had decided what the hell she was going to do with all this stuff. And she had two choices. One was to divide between the different cousins who had survived. One of them is my grand-grand-grand-grandfather. Or to give it to the state that the next generation in the future, could see what de’ Medici did. And that’s what she did. And she gave everything to the city of Florence. And everything which is in the museum, the Uffizi, is a gift from her. Everything which you have in all the museums of Tuscany is a gift from her. On the other side, the small things like villas, land, wineries, some pieces of art, money, went to the cousins. But the basic art collection went to the state.

When you were about 30, you moved to New York. You were living in Switzerland and brought up in Switzerland. A privileged life brought up in Switzerland, would you say?

Yes, probably.

Why did you move to New York? What was the idea that you had?

Well, that’s simple. Listen, I am of the generation and born in 1951. I was 17 when I went to the 1968 revolution in Paris. I had this culture of what you saw in TV was all American series, American films. Very American. It’s a poor America. So America was like a dream, by the time, 50s, 60s. It was accessible, but I never went to America. So I used to travel to Europe.

You were in your 30s when you went to America. Is that because you were most free then, and you weren’t free to do it, psychologically?

It was just a question of timing. A certain point after I lived in Switzerland for so many years, and I tried to go back to Italy, where I never lived. And I said, when I was in Italy, I said, what the hell am I doing here? I have nothing to do with this people. And I say, okay, that’s the time to go to see something else, and then I decided to go to New York, knowing nobody, knowing no idea where I was going to move, knowing no idea what I was going to do. So I just moved to New York, and I went to the Sheraton Hotel in Seventh Avenue, and with the jetlag, I woke up at four o’clock in the morning, and I went immediately in the street. And I was there, and then moved to Avenue of the Americans, Sixth Avenue, and I was watching those buildings. And I said, I did it. I am in America. It was the achievement of a desire that I had since I was in the age of thinking about 14, 15, 16. It was 1978, so I was 27.

So you find yourself in America. Within 10 minutes, you meet Andy Warhol.

I met him in Studio 54. It’s very funny, because when I was there, I knew absolutely nobody. And I was nobody.

So you as a de’ Medici found yourself, maybe one of the first times in your life, feeling like a nobody, because you were in America, where everything is bombastic.

And I was very happy. So one of the myths I heard was Studio 54, and Steve Rubell. When I arrived there, I met a guy, and he said, where are you from? What’s your name? The Americans are very curious and they want to know how much money you make per year after two minutes, which is really boring. There was Andy Warhol and Liza Minnelli and her sister Lorna Luft and Calvin Klein. I’ve been introduced to them, so everybody said who is this guy? I said, I’m Lorenzo de’ Medici. They said you’re kidding. So I had to show my passport, and it was incredible for those people. So they start to invite me to their home, to the dinner parties. And the American is very easy. You go to the first house, and you have 100 invitations immediately. And that’s how it happened. And Andy Warhol invited me in the studio, and he says, I would like to make a picture of you. And by that time, I thought, uh-oh, this is dangerous. Because he was obviously very gay, and he was horrible, physically. And so I left and didn’t want them, which I regret for the next 20 years. I regret not to have it. But that’s how it went. And then in one of those dinners, I met a gentleman, 60 years old, and he said, I’m making wallpaper. And for me, wallpaper was something horrible. It was something typical from America and England. So he said, would you like to visit the fabric? And I said to myself, well I have nothing to do, what the hell. So he sent a car to pick me up, because I rented an apartment in Soho, and the car took me to the airport of LaGuardia. And it was a plane waiting for me. He didn’t tell me that the fabric was in Florida. So I said, what the hell. And we went to Florida, and the fabric was an excuse to show me his plan, see his lifestyle. He was so impressed with me. And then at the end, he showed me this collection of wallpaper. I couldn’t lie—they were horrible. I mean really old-fashioned. So he was really surprised, and he says, well, are you capable of making a collection for me? And I said, well, I don’t know. I’m not good at drawing. I can try to put some ideas on paper. And when I went back home, I had no idea how to start, so I knew a designer. And I said, look, would you help me? And so we put together seven drawings. And then I went to the guy’s office, and I showed him the seven drawings and they discussed with other people in marketing or whatever. And they said, okay, we are going to buy the seven drawings, and we’ll see what we can do with it. I said no, I’m not selling the drawings. If you are going to produce them, I want two per cent on the sales. And he was so surprised, but he accepted. And that was my first living, making money like this. And the first year I made something like $200,000, which at the time was a lot of money. It was not very interesting in itself, as the work, but then he made fabrics with the same drawing of the wall, and he asked me to photograph everything together, which I didn’t know how to, but again, I call a guy which I knew who was a very good photographer of houses, and he helped me to do this. So I always asked the help of other people, but we ended up to do something like this. After four years, I was asking myself what the hell I was doing there, in New York.

Did you feel a fraud? Was it imposter syndrome?

No. I was always very sure of myself.

Did you feel that you deserved that money from those people?

Absolutely. If somebody is willing to pay you for what he thinks is your art, because it was my work also, it was not only the work of my friends. And my friends will never get the work if I didn’t give them this. So it’s winning-winning.

Do you feel the same now?

Yes, absolutely.

You write books, which contain a lot of references to art, because of the family. And you write mainly historical. As a writer now, do you feel in any way fraudulent? Are you writing about what’s inside you? Are you just documenting what you know? Because your books tend to be a mixture of what was historically correct but also your particular view on it. It’s very family centric. It’s handed down to you.

I became a writer by accident. Because I met some editor who asked why don’t you write something about your family, it would be interesting to have a book about it from the inside. And that’s how I started. And then I wrote a novel, and the editor told me no, no, no, people want to have something from de’ Medici from you. Anybody can write a novel, but they cannot write a view from de’ Medici. So I found an compromise, I’d write two parallel stories in each book. One is a contemporary story and another which explains what happened in the de’ Medici time. So there is a de’ Medici story in that time, and a today story, which explains why some events happened.

So it’s a reflection from today.

In a way. For example, in one book, The Stolen Paper, it really happened that they stole the papers of the queen Marie de’ Medici in France, and I explained how they were stolen, why she wrote those letters, and things that you don’t know today. So I explained this. And to explain this and not to be a boring historical book, I invented a story around a woman professor from Brown University in the States who came to Europe.

How many languages do these books get translated or published in?

They were strangely translated in 17 languages, but not English.

How does that make you feel, considering the breadth of the story?

It’s really frustrating. It’s very frustrating.

Why do you think it hasn’t happened?

Because the British system in my experience is different. In Europe or in South America, where I sell my books as well, Mexico, Argentina, Colombia, etc., they take a book I write in Italian.

Do you consider that to be your mother tongue?

No, not really. It’s my mother tongue but I will admit I will speak Spanish mostly. My mother language is really French because I studied in French, we were talking French at home, and I’m calculating in French. I speak six languages. It’s frustrating in the sense of, if I could publish in English I would have a much wider public than if you write in Italian, or if you write in French.

I want to ask you about what role, if any, art plays in your life now. We’re sitting in your lounge here, and I can see two separate pictures. One is one of your ancestors. Who is that?

That’s the Grand Duchess Vittoria della Rovere. She was Grand Duchess of Tuscany, daughter of Claudia de’ Medici, married to Ferdinando de’ Medici, mother of Cosimo III de’ Medici. It’s from 1662.

The other side of the fireplace, there is a picture which is mainly in gold.

Who is the artist?

It’s me. It’s my work.

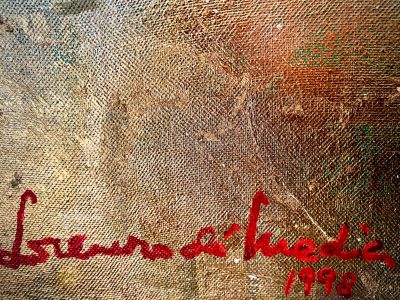

Why is that in your lounge, in a place of equal prominence to one of your ancestors? It’s a major piece. And it’s mainly gold. And it’s abstract in its approach, and it’s signed at the bottom in red. How and why did that come about?

It is very simple. In my previous house, I needed something red on the wall, and something big. So I went to ARCO in Madrid, which is a fair of artists and art. And I was looking for what I need, and the first painting I find in red signed by nobody, they asked me 5000 euro for this piece. And I said, well, I’m going to do it myself. And so I went to a shop, I buy all the materials. And the guy of the shop said, why you don’t go do it in gold and I don’t know how to say it in English. They sell you small packets of gold. And I bought this and went home, those feathers of gold were flying all over the apartment, it was a terrible mess. But then I added different paintings in gold on the top to make a form. And that’s it. And then somebody saw it in my in my house and said, oh, it’s beautiful, why don’t you do one for myself. So I did one and I sold it to him, because it was a lot of work. I sold it for 6,000. And then another friend said, I want also one but smaller. I said, forget it. I’m not interested.

So your art career was very short-lived?

Yes. But maybe one day I will come back, because I have some ideas. Some days I have the lust to do another painting. And so I’m thinking about it.

Why should anybody care whether you do art or not?

Oh, it’s not really your business. It’s not even mine, because I don’t know myself if it works, or not. What I don’t want is to have my house full of my paintings. I think it’s horrible.

Why is it horrible?

It’s in the auto suggestion, self-promotion, which I don’t like.

You want your house full of other people’s art. I can see a lot of art around your house.

Because I like it in general, and it reminds me of moments, of things, or special times of my life. And it’s important.

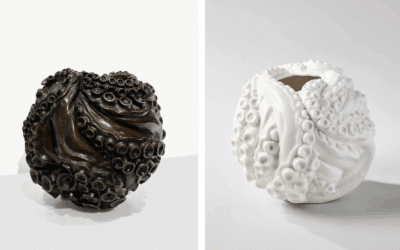

The place of prominence is the picture of one of your ancestors. But you’ve also got a lot of other art, sculptures, even furniture, and house things. The ashtray you’re using in particular looks like a piece of art. Is art important in your life?

I would say yes, because what is important is the beauty. And if you like a piece — you, not the other ones — if you like a piece, if it’s important for you, then it’s important.

Why is it important for you?

It’s important for me because it’s an expression of a talent, and you can appreciate it. If you look at this bust, it’s lots of work to do this, this is an unsettled state of mind. It’s in marble, and it’s a huge work, and I think I will not be able, I will not have the patience myself to do this, and if you do the wrong things at the end, you can break everything. You have to respect the work.

So is technique more important than the message? Or is the message more important than technique for you?

I think that technique is very important, because somebody with no techniques has no future, it’s not interesting.

Banksy.

Banksy, I first hated and then I really liked it.

Why did you first hate it, and then why did you like it?

Because at the beginning I think it was just painting the wall, a house, from outside. It’s nothing, there is no message.

Do you think it had no message at first, or was it that you weren’t aware of the message? What do you think it was?

That’s an interesting question. Probably I wasn’t aware of the message. But if I don’t see a message, other people will not see it either. And now, I think he’s a great artist with a lot of fantasy. I really love him. I really like him.

What do you like most about Banksy?

The colours. The use of the colours that he makes.

Even if it’s monochrome? A lot of his stuff is monochrome.

Yes. For example, he rented a boat to have the refugees. And he painted the boat just enough, not too much. And that’s this touch of Banksy, which is very important. It’s all red. It’s only red, a little bit of white, but it’s basically red. And that’s the Banksy touch which I like.

So it’s that minimalistic thing?

Yes. I mean, just enough to know that it’s Banksy.

Is it the fact that he’s using the least materials possible for the biggest message?

Yes, I agree. I think that’s the way it is. I think he used the least material.

Some of the Renaissance artists that you have, almost by default, studied in terms of your writings, what would you think they would recognise in contemporary art? And what would surprise them?

Nothing. I think they would not be surprised.

Why would they not be surprised?

Because there is nothing which is extraordinary that we come up with, you’re shocked when you see it.

What about pieces of elephant shit on the wall? You get a Chris Ofili, or what about a Pollock?

Christo who just wrapped the bridges. And I always thought it was uninteresting for me. I didn’t see the point there. I mean, just to make marketing, to make it to shock the people, but I didn’t ever see it as art, myself. You will be amazed the number of people who wrote me through Facebook, to ask me to patronise and to mecene their art. There is a lot of artists, they still think that we are mecene, and they are offering me their work. For example, there is a guy who wrote me last week and he said I would like to make a painting of you. And I asked him, what the hell would you want to do with a painting of me then? And he said, well, I will offer to you and I said well, I don’t want a painting of myself in my house. He did not understand. There is a photographer from Germany who wants to come here and to make a photograph of me, and I said why? He said because I’m printing books of art and I want to photograph you for insert image in my book. I am massively amazed after so many centuries, people still have the image in their head that they want something from me, because I am a nobody, I just have the blood of de’ Medici. I’m not a great artist, I’m not a Nobel Prize winner for literature. I’m a very common person, but they want something from me.

Do you feel a responsibility? And do you feel the weight of having the name of de’ Medici?

Of course.

What is positive about it, and what is negative about it?

Well the positive is that it opens every door, in the good sense of the word, right. For example, recently, I had somebody I know who was stuck in Argentina, and he couldn’t come out because of the virus, and in Europe was his daughter with cancer, and he wanted to come and he could not leave the country. So I called somebody I knew, who was a Spanish senator, and I said, Can you help me? And he called the minister, the minister called the ambassador. So the guy came to Madrid. And I think thanks to my name, there is something good I have made. Now, the bad part is a lot of people are approaching you with you don’t know what intention. A lot of people say they’re very interested, and it’s very baffling because I’ve been a de’ Medici all of my 69 years, and I really don’t give a shit about it.

Do you feel that people try and exploit it?

They try.

You’ve still got an almost daily involvement in art. For example, next month, you’re going to be partaking in the Hay Festival. Can you explain why, and what you are doing?

Four years ago, I was invited to my first festival, because it was coming out the series of the de’ Medici, with Dustin Hoffman and Richard Madden. And they wanted me to present and comment about this occasion, which I did at the Hay Festival of Culture. And it was full of people. And they were so amazed there were so many people interested, they invited me the next year to talk about de’ Medici. So I talked about a book of mine and de’ Medici in general. And again, it was full. And last year, it was the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci. So they asked me if I could talk about Leonardo da Vinci and I made a conference about it.

The reason that you have so much knowledge about Leonardo da Vinci is subsequent to your family being patronage to him, but it’s your research that you’ve done.

Sure, because you don’t know everything. If you make a conference, you have to know what you’re talking about. And especially at the end, there is questions and they always surprise you.

Do you consider yourself to be an expert on da Vinci?

No, absolutely not.

Are you saying that in the context of in comparison to art historians?

Yes. So this year, they asked me what I want to do because they want me there again. And the ambience of the festival, where there is an exchange of culture, of architects, of philosophers, of writers. It’s very nice to be in this ambience. You are there just three days but it’s nice and you eat with people you would never meet. Last year I ate with two big Spanish writers, and Norman Foster, the English architect. And he was very nice to me. So this year, I said I would like that we organise an exhibition of pictures, made by my friend, the son of the Aga Khan. And they said, oh, that’s a good idea, and you could make an interview with him. I said an interview, no, because it’s a friend, so I don’t want to ask questions. So I suggested we make a conversation about his interests and his fears, whatever. So that’s what we are going to do. Meanwhile, I had an idea, so I’m preparing also a documentary for the television about him, about the Aga Khan, diving for filming under the sea, how is the life on board, how we prepare an expedition, why we do the expedition.

Give me some context about the Aga Khan. Where does this diving ship come in?

He had the passion for the sea since he was a child. When he was 14, he had a tremendous accident, because he was with a diving teacher, and the teacher pushed him up too fast, and he got handicapped, he cannot use his left arm and left hand, and left leg. He’s a lovely person and still doing this in the water. And I asked him, how can you swim if you cannot use your arm? And he says, oh, because I’m palming, he used the palm. It’s interesting. And so he made a very beautiful picture, which has been published by National Geographic. He’s trying to make himself a name. Since we are good friends, and people always laugh about us because they say, the two princes. It’s kind of fun. So I’m really looking forward to doing this documentary. And if it’s successful, it will be a TV series.

So even for 2021 Hay, there’s an exhibition that’s financed by a wood manufacturer?

This year they financed something which I haven’t seen, it seems that they are stone in wood. Bricks are being made out of wood, and all the prominent people will come by, take one brick — it’s a wall, you destroy the wall, and there is a message behind each brick. So you have to read this message. And that’s just the people who are interested to come to see, then it’s an expense. And the other one we were talking about is to put together five artists and five thinkers. So you for example, you think of an object, which could be small or big, it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t have to be useful, just something you have in mind. And then, we put you in touch with an artist who will realise the piece in wood. And those pieces are exhibited during the festival. And then we have organised in this case, but it went down for another reason, which I will explain to you. We organised an exhibition also in Lisbon, in a palace, which is also a museum, the Palace of Ajuda.

So the Hay is still going to be in Segovia, but there’s going to be another offshoot moving to Lisbon?

It stays the exhibition of the wood here, then Lisbon in January for three months. And this year, we had a problem, because the previous exhibition was in Poland. And, of course, the American union gave a budget. And it seems that in Poland, there has been a huge financial problem, and the cost was three times the budget of the union. So the budget was $400,000, and sadly, it cost 1 million. Something went wrong, so they decided to suspend this project until they clarify the situation. And that’s why it was not made.

So next year the Hay will move from Segovia, follow on in Lisbon from January to March in 2022.

Yeah.

Wood is my favourite material. It’s warm, it can be shaped, and it’s easily available and transportable.

And it’s something alive.

What do you particularly like? We’ve talked about this before, and wood seems to be quite an important material to you, although wood hasn’t been a great part of the construction of great art. Unless we’re talking about something like the cupola, in which it was a foundation of things, for building a bigger dome, a smaller dome and then a bigger dome around that. The de’ Medicis were involved with the cupola of Florence. So why is wood an important thing for you?

I will give you a very rough example. This painting you were mentioning of Maria Vittoria, the Grand Duchess of Tuscany, a direct ancestor of me. I have several of those paintings, but I keep them in Barcelona, because I don’t want my house to be a museum. All the walls are full and there is no space. The most important of this painting is the frame in wood. The frame is from a guy called Salvatore, and he is a very famous painter of that period. It’s a very simple frame, but elegant. And it’s in wood and plaster. If it would not be wood, what will it be, going back 300 years? I have several antiques, and people come here and they say, oh, the frame is fantastic. So they notice the frame before antique. It’s funny.

And so you’ve got a relationship with wood, I can see around that there’s wood.

Look at the throne as well. I mean, there is wood everywhere.

Why do you think we as human beings love wood as a material?

Because it’s a natural resource, which is available to everybody. It’s important that it’s a natural resource, you cut a tree, but then you can plant another tree, it’s endless. It’s not like a vegetable which can go wrong. Wood is very important.

Do you therefore respect, say, an acrylic paint or material less? What about a digital artist? What do you feel about multi-process, multi-material?

What I admire is the invention of using those materials. Who would have thought about 20 years ago? So it’s something really new, and the modern world is offering you this possibility. It offers to the people a chance to develop a new idea. I mean, 20 years ago, you didn’t have this computer, you didn’t have this iPhone. It’s something very recent. And the modernity gives you all this possibility that you didn’t have even 50 years ago.

But it makes life easier. Should an artist feel good about making his life easier? Should an artist toil more? You respect the toil of a Michelangelo on his back. Is that worth any more, or is it his art? Is there a tipping point where that art is worth more, because it took him so long and he nearly crippled himself? How do you feel about that?

I mean, I don’t think it’s comparable. I think we’re talking about two different worlds. And you can place an adolescent teenager in front of a Michelangelo painting, and he will not understand, but he will understand perfectly the laptop that you are using. So it’s new generation, new possibility, new instruments to develop your art. And you have to respect this. For example, there is people who said there is no more culture because people don’t read any more. Yes, but the boy of six years old, who is capable of playing on your computer or your iPhone, it’s a new culture, it’s a new way. It’s something new. I mean, you have to respect this. Maybe this is the culture because for example, it’s a culture I don’t have. I barely know how to use my iPhone. And a boy of six years old, he knows better than me. So you have to respect this.

Why do you have to respect it? Why do you not dismiss it?

Give everybody a chance.

When you say give everybody a chance, does that mean that if it was in your power now, you would give some people a chance in terms of art and you would patronise the same way that your ancestors did? Or would you patronise a digital artist now if it was in your power?

Definitely.

So what makes your decision? So if I can give you the power to do that now, and I could present you with what I believe to be the best six digital artists, what are you going to use as criteria for whether you patronise them or not?

I think it really depends on the person that you present, because the person has also to sell himself. In a certain way, we all sell ourselves. If he sells himself, showing what he makes, and I like or appreciate them. I mean, not understand, but I like it. Because people always make the mistake, if you don’t understand, you don’t like it. That’s wrong. Because you don’t understand doesn’t mean it’s not beautiful. And you have to be open to everything, to all kinds of art, to all kinds of material. It’s very important to have an open mind. And if you present 12 and I have to choose three, it will be very difficult, and I don’t know exactly what criteria I would use. Probably I would be influenced by the person who’s selling me his design.

What about the artists themselves without the human factors? How much do they play? So your human factor, art. Shit art, nice guy. Not nice guy, great art.

No, it doesn’t work like that. You could have a very lovely person in front of you and very charming, and you don’t understand, you don’t like what he does, and that’s it.

If art connects with you, would you patronise it then?

Yes, absolutely.

What are the criteria to connect with you? How do I connect with you if I present art now if I say I want you to patronise me?

Show me something that is different.

I believe in one thing. The gene of the family gets from an individual to the other. And my family has always been oriented to the art, and I think this is an interest that passed from generation to generation. One can say, yeah, it’s easier if you are born in a family, which is artistic oriented, who will read books, and listen to music, it’s easier for you to be brought up in this ambience. Instead of if you come from within a low class media, then you didn’t have all these possibilities.

So are you a product of your environment, or are you a product of your genes? Or do you think it’s both in terms of art for you?

I think both, because the interest of the art doesn’t come alone, because you have it in your genes. And I think I have it in my genes because I’m always interested by the beauty.

So at the end of the day, beauty is what drives you.

Beauty is essential.

All photography by Danny De Matos

Danny de Matos (aka Lisbon Kid) is an alternative electronica producer, writer and DJ. He also guest lectures at Point Blank, London’s pre-eminent electronic music school. He is Portuguese, married to Lesley, a father to Lúcia, and a fan of Setubal region red wine.