[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;]T[/dropcap]he title of this three-person-show was bestowed by its curator, the gallery owner, sid motion. ‘A Romance of Many Dimensions,’ is the subtitle of Edwin A. Abbott’s 1884 novel, Flatlands (Abbott 2010). In his novel, Abbott introduces the reader – an occupant, as we all are, of Spaceland – to a narrator, a square, an inhabitant of a two-dimensional world of plane-geometry and its flat-shaped forms. The narrator has the task, through the novel, of acquainting the reader with the ways of life in a two-dimensional world.

The gallery is in what was, until two years ago, a William Hill betting shop. Its position is pleasantly surprising, incongruously sited in an old-fashioned parade of shops. It stands next door to a kebab take-away, and just along from a laundromat, a convenience store, and a greasy spoon café, all set back from the busy York Way by a small green common space. Opposite is the newly developed canal-side Granary Square, home to Central St Martins School of Art, University of Arts London. Thus, do strange collisions characterize contemporary urban life.

The gallery pledges an ethical commitment to contemporary art, unusual in London at the moment. (It recalls the likes of the Lucy Milton Gallery in Notting Hill in the early seventies, Nicholas Logsdail’s Lisson Gallery in the late sixties; and, more recently, Peer, over in Hoxton.) Motion is committed to the exhibition of artists whose exceptional work might not otherwise be accessible. Over the two years of its existence, it has shown artists of all ages, but whose work has been concerned with contemporary thought outside mainstream fashion.

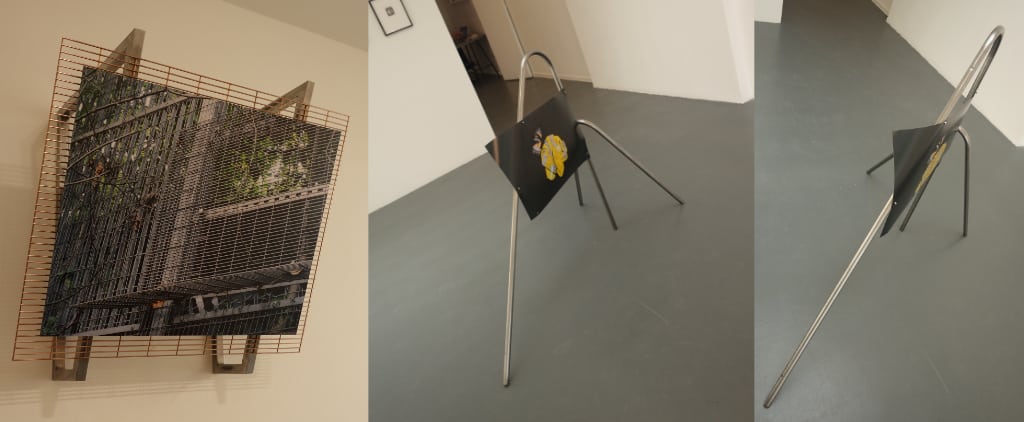

Matthew Barnes is a photographer. And yet his work is distinctly three-dimensional – at first blush we are tempted to think it is sculpture. What makes it interesting as photography is its insistence on its materiality. The three-dimensional props incorporated to hold the photographs permit the print to curve under its own weight, so that a top corner rolls slightly and takes us around the photo to its blank reverse side.

Matthew Barnes, (from L to R), Behind Victory, 2018, Elevated Cigarettes, 2018, and detail

The Transparency of Photographs

That is, the photograph insists on its real three-dimensionality – over and against its contextual reading as a transparent picture.

The philosopher Kendall Walton has claimed that photographs are prosthetic devices that put us in perceptual contact with their subjects (Walton 2008). Just as microscopes, telescopes, night-vison glasses and television sets enable us to see the otherwise unseeable, so, when I look at a photograph of Marylin Monroe, I am literally looking at the famous film star. I see her, in the picture, across time, in one static moment.

The Photograph as Object

It is, therefore, an achievement of Barnes to turn our attention back to the photograph as a physical entity, notwithstanding its pictorial nature. The nature of photography is transparent, and as such it is two-dimensional. The image has no thickness, even if the paper upon which it is printed has: even if the ink sprayed on that paper surface has thickness, it is not what we see when we see the picture.

Another clever moment is when we look up at a screen, a photograph held onto the same metal grill of which it is a photograph. Again, Barnes reforms the convention of looking at photographs. He has us turning our necks toward the image, placed like a pub television, we look at on ‘Sky Sports Super Sundays’ to drink lager and watch the football match unfold.

And again, we have no hesitation in saying we watched the game, arguing convincingly that their goal should not have stood as the ‘scorer’ was at least a yard offside. We unhesitatingly treat television as transparent in Walton’s sense. One reason for the positioning of the telly in the sports bar is that it affords viewing from a packed bar – its height and angle standing instead of the raked seats of a theatre. That was handy for the packed private view. Barnes is to be thanked.

The Second and Third Dimensions; and the Space Between

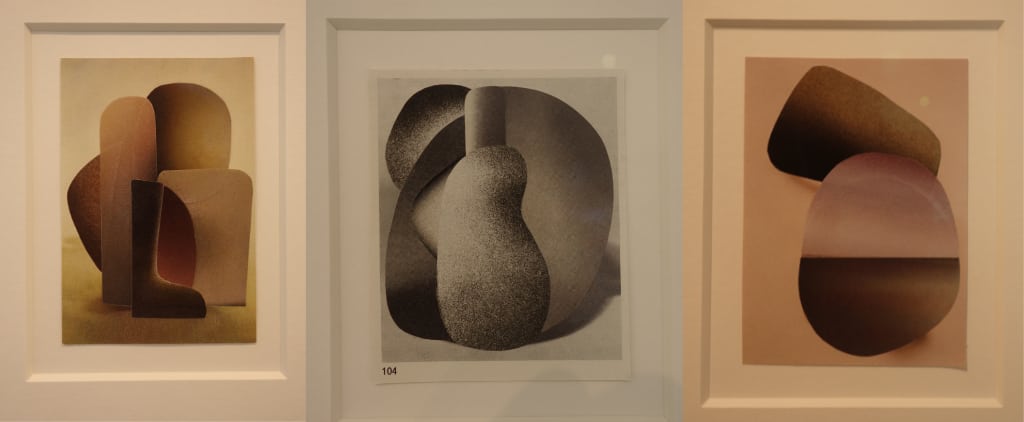

Hannah Hughes’ work consists of finely cut shapes from magazine photographs that contain modelling derived from the lighting of the original photograph. She places these into a pictorial space that contains the ‘new objects’ as if in still lives or, conversely, grand landscapes. The modelled objects deliberately occupy a stretch between Flatland and Spaceland, a sort of 2.5-dimensional world we know cannot exist. There is a world into which we have to peer; and the collages exploit the smallness of these delicate compositions. Our probative looking is prompted, prescribed, and pre-positioned by the gap between Flatland and Spaceland.

That gap is traversed by every act of depiction as it generates a collision between the perceived flatness of the picture and the imagined depth of the world seen in its surface. The photographic abstractions she achieves in her cut-outs pull toward both flatness and the spatial modulation of these new objects ‘in-the-picture’.

Hannah Hughes, (L to R), Untitled #85; Untitled #80; and Untitled #35. All from Flatland Series, 2018.

If it is in the nature of depiction, quite generally, to do this, then Hughes’ work is significant in pointing it up by making pictures out of transparent pictorial recordings. The modelling of the original is transposed in the new setting so that we see it as ‘modelling removed’; and then we are provided a new space in which the objects breath with shallow inhalations. The colours are at once flatly local and spatially distant. I am reminded of Wittgenstein’s remark,

58. Imagine someone pointing to a place in the iris of a Rembrandt eye and saying: “The walls in my room should be painted this colour”. (Wittgenstein 1978)

And again,

117. I saw in a [black and white] photograph a boy with slicked-back blond hair and a dirty light-coloured jacket, and a man with dark hair, standing in front of a machine which was made of in part of castings painted black, and in part of finished, smooth axles, gears, etc., and next to it a grating made of light galvanised wire. The finished iron parts were iron coloured, the boy’s hair was blond, the castings black, the grating zinc-coloured, despite the fact that everything was depicted simply in lighter and darker shades of the photographic paper. (ibid.)

In these paragraphs, Wittgenstein makes two different but related points. Together they bring into focus an important feature of Hughes’ work – that it operates between two depictive schemes: painting and photography.

Colour in Painting

In a painting, the colours are internally related – think of, as a prime example, Seurat’s shadows and their geometric relations to their well-lit aspects in the modelling. Seurat believed, wrongly, that in the science of optics, shadows would be complementary colours of the lit surfaces of which they shared the same local colour. And his Pointilism was a way in which he could better develop this position. More broadly, painters learn to develop restricted palettes, usually of the three primaries, one warm, one cool, of each. Plus black, white and a couple of earth colours.

Now the “pale blue of a highlight on the iris of a Rembrandt ‘eye,’“ transgresses the distinction between two things seen. The first is the pale blue perceived on the surface, the second is the highlight of the iris seen in that surface.

In the second paragraph, Wittgenstein makes a related point about the limitations of what it is for us to see a monochromatic surface and to use that surface as an object upon which to project the blondness of the boy’s hair. There is a gap between the grey part of the surface that locates the boy’s hair and the blond hair we see on the basis of seeing that patch. Thus, there is something quietly unsettling about the transposition of the photographed modelling as it is recruited by Hughes to the new composition.

Further, Hughes exploits an existential difference between photography and painting. Photography is fully extensional, whereas painting is not. If a is a photograph of b, then there is some b, of which a is a photograph. Painting requires an intensional account. For, it does not follow that if a is a painting of a unicorn, there is some unicorn of which a is a painting. From all of this, it follows there cannot be photographs of unicorns.

Add to this, a claim made recently in a lecture by philosopher John Kulvicki, that if you cut a photograph into pieces, each piece remains a fully extensional photograph (Kulvicki 2018). That is not so with paintings. (It’s not clear that, in new digital photography, when reduced to a single pixel, the photographic relation remains intact. Although, it might be argued that this single, let’s say yellow, pixel is causally related in the correct way in which it ‘records’ an element in the larger depicted scene; and so retains its photographic status. However, a cost accrues. For, even if the single, simple, non-relational, yellow pixel retains its photographic status, it can hardly be argued it retains its pictorial status; and if not, the photographic and the pictorial would come apart. This is surely the point that Wittgenstein makes about the nature of a simple part and the pictorial whole in paragraph 58 above.)

Nevertheless, this ‘obstinacy of the photograph’ persists in Hughes’ pictures. The elements remain photographs in Kulvicki’s terms, and remain sufficiently complex to support both the photographic and the pictorial. They become paintings, however, in terms of the replacement visual identities assumed in the framed settings now invented by Hughes. This gives her pictures their eerie atmosphere: the 2.5-dimensional world with its tension between Flatland and Spaceland.

Hannah Hughes discusses her work at The Bakery.

Flat Sculptures

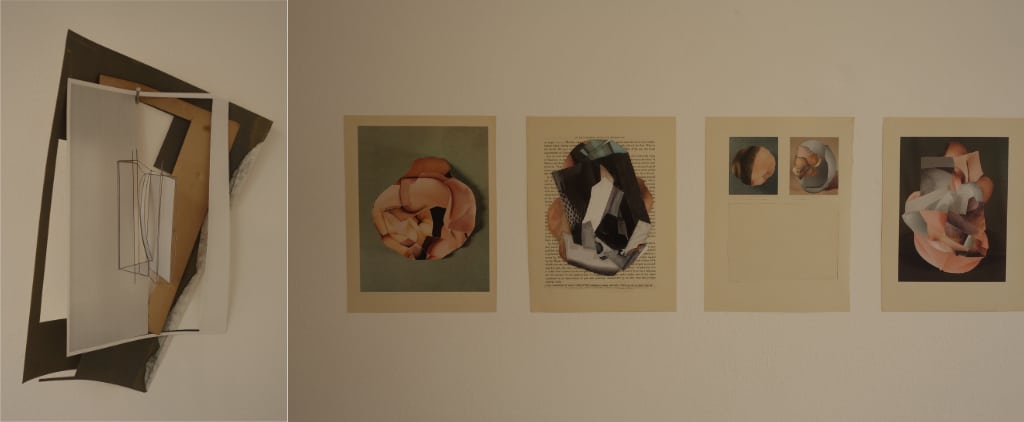

Abigail Hunt’s sculptures are, all but one,.. FLAT! They are carved out of photographs and pieces of paper and text – two-dimensional media. The exception, The last place, finally, is occupied quite simply, 2012, edited 2018, is itself cut from two-dimensional sheet but curves away from the wall, rather in the manner of a Vladimir Tatlin relief construction. What connects her work with the constructivists is a preoccupation with edge and line. Flat sculpture makes sense as a way of directing a certain sensibility toward the work.

Abigail Hunt, (L to R), The last place, finally, is occupied quite simply, 2012, edited 2018, Mamamilk II, 2018, Your gaze sees only what it meets, 2017, Mamamilk IV, 2017, Mamamilk I, 2017.

Pace Abbott’s Flatland musings, lines have neither breadth nor depth. They have only length; and so, they are invisible. The best we can do is abut two colours and describe the line as their junction.

Hunt’s work carves out positive shapes and then, painstakingly, carves out the same negative shape into which she places the positive – making for a flat plane overall with no overlaps. The carving of the positive and negatives is an intricate process made necessary by her commitment to the abuttal of shape in the solid plane. In one of her works, a series consisting of four pieces, Mamamilk IV, the titles beneath the two images have been removed and replaced by a positive cut out the same shape as the removed title. Beneath the two images, more than half the sheet remains unoccupied. It makes for a beautiful extended sigh of calm; and its flesh colour makes it like flat skin, upon which has been added modelled flesh.

In the four pieces in that series the images are cut from breast cancer illustrations and from pornographic magazines. The resulting images are fleshy obloids, not unlike a stem cell grown, if left unfettered, in some futuristic sci-fi laboratory.

Unlike Tatlin, these works are distinctly, if sometimes uncomfortably, human. Whilst Tatlin was more architectural, developing the kind of environment in which the new man might take up his accommodation, Hunt’s work is more about the new human herself, who shall inhabit that space.

The Flatness of the Image As Seen From Spaceland

As the title of this exhibition suggests, the artists here are thoughtful about the nature of depiction and the world of objects into which depictions are placed. Abbott’s metaphorical story is a good place to start thinking about the world of two dimensions in relation to the three-dimensional world in which we live out our days.

However, the metaphors soon break down. Women are lines in his story; and so, being difficult to see end-on, they are bound by law to wag their tails, which is amusing. Workers are isoscelese triangles and are likely to cause severe injury if run into, such are their sharp ends. Abbott has a good laugh at our hopes of social mobility, which is upward generationally. Squares beget pentagons, who in their turn beget hexagons, and so on; but in the end the characters of Flatland lack depth.

The work in this show creates a conduit between the perceived flatness of images and the three-dimensional worlds into which those images are portals.

An interview with Hannah Hughes is published with The Bakery.

References:

Abbott E. A., (2010) Flatland: A Romance in many directions, Cambridge University Press

Kulvicki J., (2018) Lectures and seminars contributed to the graduate seminar at Institut Jean-Nicod, Ecole Normale Superior, Paris.

Walton K. L., (2008) Marvelous Images: On Values and the Arts, Oxford University Press

Wittgenstein L., (1978) Remarks on Colour, Berkeley: University of California Press

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.