The fun part is having relationships with friends, building something real between people, celebrating people, and seeing the paintings go out into the world and be further celebrated and experienced is exciting. It depends on the person and the situation. It’s different every time. Everybody comes wanting to get something else, something a little bit different out of it.”

Continued from last week Gisela McDaniel spoke to Trebuchet for our process issue she describes the history of her relationship with painting and what it’s taught her as well as what it’s allowed her to present to others.

Does this mean that all your paintings are dealing with the connection of people to their trauma? Would you say there’s a dangerous line about defining people in this way?

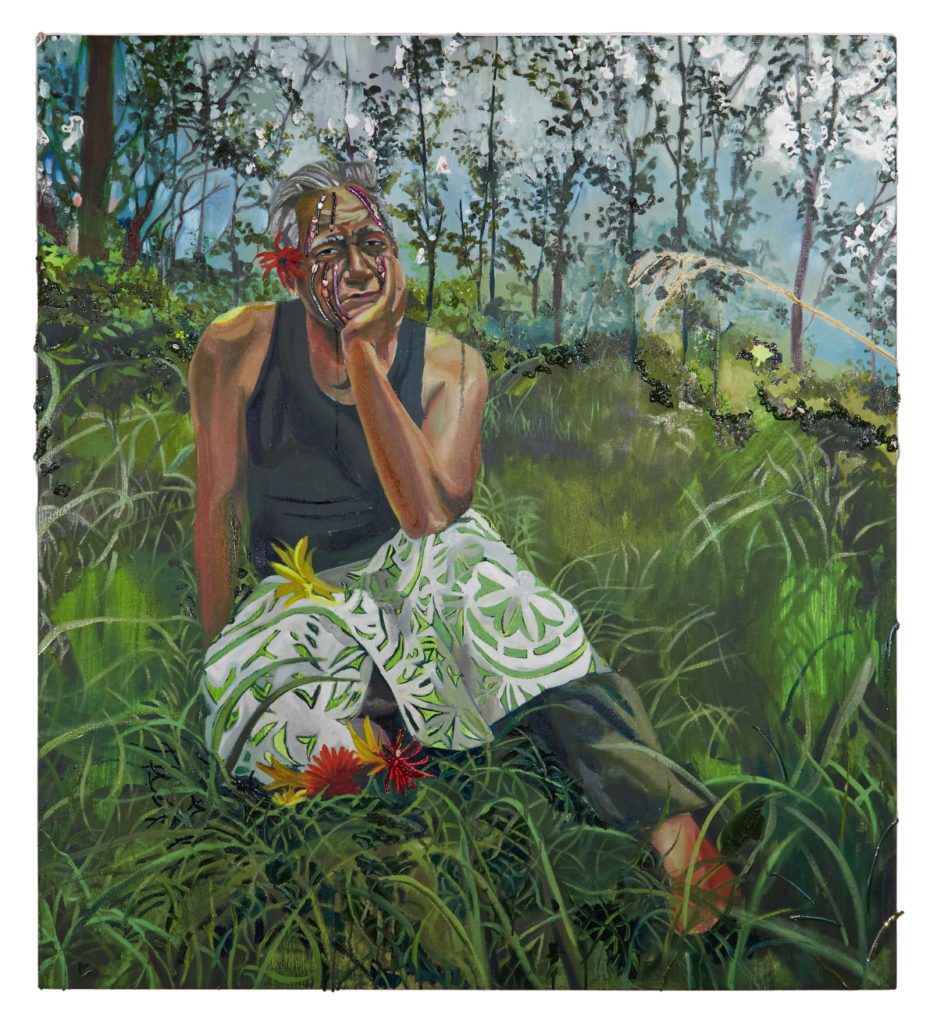

Well, quite honestly, not all my paintings are about sexual trauma. I have people come to me and want to talk about that. I’m always willing to do those interviews, but actually I talk to people about all sorts of things. In the past I’ve talked to people about being indigenous, about their relationship to food sovereignty. I talk to people about their identities. All of which is about storytelling and history more than anything. [Originally] remembering that the totality of [experiences] was for me that was something I needed [when I first got started]. As a survivor, I needed to tell my story. That’s a space I’m gonna [continue to] hold for people. When I first got started, that was just something that I needed to do. And it was something that helped me heal. And my view was: ‘Okay, if this is helping me, then maybe I should try to do this with other people and see if that helps them’.

It’s been overwhelming for it to be something that’s being consumed globally because I never, never, expected that – it wasn’t the goal. The goal was that this is a practice that was necessary for my own healing journey. And that I was in a community, what I was doing with a lot of these paintings was amongst that community. I never did this because I wanted to be “famous”. It’s not about me. It’s about the act of setting something down. And a lot of art students go through this period where they’re ‘Okay, what do I want to make my work about’? And while I think I’ve come to a place where I’ve got a perspective, an answer to that question, it’s not been in the easiest way. Because art can be decorative, flashy and something that’s consumed and that’s never been something that’s been easy for me, because when you put artwork in the world, we put any work on the world, people are gonna take what they want from it. People are going to have their own ideas about it. But for me, I’m more focused on making sure I’m in right relationship with the people that I’m painting, making sure that I’m checking in and that they’re pleased. There’s a lot of [emotional] work that goes into staying in communication and staying in a relationship with them. [My paintings] are not about anything specifically but focusing on that singular celebratory moment, or making sure somebody feels loved. Because that’s what a painting has the power to do.

It’s surreal to see yourself in an artwork. I remember when I went to museums and I saw a person in a painting, I always wondered who they were and what their story was. And oftentimes you only know the artist’s story, you don’t know the relationship they had [to the subject], and it’s not always [been] the best [relationship]. And so, thinking about the history of relationships between painter and subjects, I’ve been very intentional about making sure there’s care through every step.

When I incorporate objects, like jewellery, in my paintings, I’m thinking about the things we wear, the things we adorn ourselves with on a daily basis. It’s something you put on, lace, jewellery, clothing, it’s something to make yourself feel good or protected. A lot of my jewellery are gifts from loved ones. I feel that wearable objects have stories [although] it’s optional if the subjects want to give me things. Some people will give me broken things, some people give me rocks, some people will give me an old dress. It’s exciting to put physical objects in pieces, because as somebody who is partially indigenous, I go into museums and see all these artefacts that are stolen objects. And who got to decide whether those objects made their way into that museu, that exhibit? I turn it around and ask [subjects] what do you want to be remembered with? I ask them what they want to contribute [to their piece].

[And] it’s not that I ask them to give me their most prized possession. If anything, I give them the option to be painted with anything at all. They could send me a photo. It could be a photo of their grandparents. It could be an object that they keep around the house that’s sentimental. Those are the things I physically paint in[to the work]. Because those things are all the things I don’t explain in the write ups, because that’s for them, that’s for their loved ones. The people will go up to the painting and say ‘Oh, I know the story behind this earring’, or ‘I know the story behind this book’, a message they want to send out in the painting. All the parts of my practice and the painting don’t need to be for the world. They’re between the person in the painting and the people who love them and care about them. And, it’s almost these fun little secrets, these moments. And they’re their context, clues to this person’s story, but you’re never going to get the whole story.

How do you know when a painting is done?

I don’t think anybody ever knows. Usually, I’ll be painting and then I know something’s almost done when I hate it. Everything’s awful. I don’t know why I do this. I don’t know how to paint. And then I have to push for a couple more days through it. And then I’m okay, sometimes good. There’s a lot of in-between stages in oil painting and every piece is different. There’s a little bit of a battle between the push and pull of every live edge and coloured stroke.

One of the main challenges is making sure that the person looks like themselves and it’s something that they’re, they’re gonna come to the studio and be okay, yes, that’s me. It’s more than physical resemblance too. That’s the biggest pressure I put on myself is to make sure each painting is something that they’re gonna walk into and be right with.

Super realistic paintings can be technically beautiful and amazing but not always the most exciting thing to me. Being able to see brushstrokes and being able to see where a painter was and had moments [in creating]. That’s exciting. I love it when looking at a work and being able to see texture. You can see [an actual] moment at work.

Can you name a couple of works that have done that for you, that have been important for you?

I could do this forever. I saw a retrospective of Niki de Saint Phalle six or seven years ago, and looking at her body of work, throughout her lifetime, was incredibly inspiring to me. Because, it starts with all these heavy things, it starts dark and then it gets happier and happier. And I was inspired by that because you can see her processing her life and processing all these events. It gave me hope, even in the darker pieces, because I could find myself within those. I could also find myself in the happy ones and finding that balance has been something that I’ve been chasing forever. A lot of beautiful stories start with something that’s difficult. And then you move through it, celebrate it. I love her sculptures. Towards the end of her life the sculptures were so happy and large and colourful. And then thinking about these almost monstrous sculptures she started with resonated with me. I love looking at a lifetime of work, because it’s a journey, and I empathise with an artist that is always changing, always growing, always transforming.

I get to learn from every single person [I paint] so I need to handle everything with care because these are precious stories. I often think about the things that my aunties or my grandparents told me. The stories they shared were to make sure that I had a better or safer life. I feel that with younger people today there’s a lot of experiences that I’ve had that I hope that they don’t have to live through. If I can share my story in a way that can help somebody else that’s incredible, but perhaps to do that, my process has to keep changing as well. We’ll see what happens.

Read more in Trebuchet 11: Process

Featuring: Samuel Andreyev / Ed Atkins/ Nairy Baghramian / Phyllida Barlow / Peter Van Dyck / Oli Kellett / Tae Kim / Chris Levine / Gisela McDaniel / Paul Sietsema / Jeff Muhs

Gisela McDaniel is represented by Pilar Corrias

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle