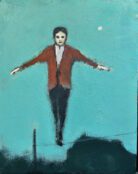

Brooding, tranquil, balancing between stillness and gesture, Gavin Turk’s Kerze reimagines a series of paintings by Gerhard Richter with an existential twist, at the same time as continuing Turk’s lifelong project to vanquish the myth of authorship.

In usual Turk fashion, the paintings in his latest solo show at Ben Brown Fine Arts look innocuous enough on the surface: simple, elegant still lifes of recently extinguished candles copied, but not really copied at all, from Richter. He certainly entertained the idea of making outright copies, but reality kicked in and creativity took over: “I started by really looking hard and…I think my original idea was I was going to try and copy them but, quite quickly, I just started making it up”. Turk’s candles are not exact copies, they rather replicate the form, style and motif of Richter’s original Kerze series, so they are copies without originals, ending up with a richer, more innovative simulacrum of Richter. It de-mythologises Richter as the uber-artist by demonstrating that his work can be replicated without loss of affect and without any trace of his hand.

Turk’s work interrogates the notions of identity and authorship, especially in the sense of how the idea of ‘the artist’ adds to, or even constitutes, the character of an artwork. The theme is exemplified in works where he portrays himself as Elvis in diamond dust prints in the style of Warhol in Diamond Yellow Elvis (2005) or as a waxwork Sid Vicious in Pop (1993), where the point is that identity (of artist and subject alike) is less important than aesthetic form. For his degree show, he produced Cave (1991), in which he cast himself as a revered artist, painting his empty studio white and placing on the wall a blue plaque proclaiming ‘Gavin Turk, sculptor, worked here 1989-1991’, for which the Royal College of Art famously refused to award him a degree. In all these works, the skewing of the identity of the artist and the continual reframing of art historical motifs begs the question: does value really reside in authorship or does the author, as Roland Barthes said, die at the moment of creation?

It certainly looks like the latter, especially when Turk creates the most mesmerising Jackson Pollock painting by signing his own name, layer upon layer on the canvas. The Nubians of Plutonia (2009) certainly looks like Pollock, but in so doing it sublimely demonstrates that there is nothing special about Pollock the artist (even if there is something special about his work). In the act of binding together the threads of art history through copying, emulating and simulating others, originality is inevitable. As Turk says, “It’s impossible for me to make something and for it not to be original in some sense”, so there is a wonderful paradox here: for all the talk of the death of the author, originality is birthed every time with the author. And so it is with Kerze, where something strikingly original emerges from the act of attempting to simulate something else as closely as possible without copying.

Turk says he did not grow up with art and only really came to it through music. Prior to the days of streaming, he says, CDs and LPs had “the square bits of artwork…And quite often you’d be listening to music and looking at art”. The turning point came during his foundation year, in 1985, when he “had gotten hold of this Sonic Youth album and…there was this picture on the front of Daydream Nation”, which captivated the teenage Turk and cast a spell that lasted for thirty years or more. Richter’s Kerze, glowing and flickering along with the sound of Sonic Youth, haunted Turk until one day he decided to finally snuff out the memory by taking a rare foray into painting.

He calls painting “a game that moves as you play”. It is certainly something of a departure, since he is best known for sculpture, not least for pioneering painted bronze, which has been commandeered by contemporaries such as Damien Hirst. Think of Gavin Turk and you think of those majestic, lifelike bin bags, or the chip fork and polystyrene cup, all rendered in immaculate reality. So this move towards painting is a remarkable turn of events. “One of the things about paintings”, he says, almost wistfully, “is that they change overnight. You spend a day painting and then, in maybe two or three days…the colours change, the texture changes, the brushstrokes – some of them come out, some of them go away”. That which looks effortless, pristine and so very haunting on the gallery wall turns out to be a daily battle: “Sometimes, you get the little brush out and you put that little brush stroke in, it can be really satisfying…sometimes I go through phases of infuriation when it doesn’t really work…and sometimes it comes out really easily”.

The solution is to introspect on his training, to return to what he knows by treating painting as the composition of distinct parts, pieces of a puzzle that need to be fused together in just the right way: “The way I approach art is very much a physical thing…I would say the paintings are kind of sculpted… and they needed to come out in a certain sort of way”. This explains the ominous righty of the candles, whose fire has been extinguished but who stand tall and proud regardless. The result is, in a sense, still life, of course, but it is more than that for Turk. One of things that drew him to Richter’s pictures, which looms large in his own Kerze, is the solid blocks of colour that frame the candles – panes of almost colourfield intensity that border the candle – which are intensified by the repetition of the motif throughout the series.

The frame is the painterly grounding of the pictures in which different candles are contained by the ubiquitous background that occupies the vast majority of the picture. It is that frame, as a swatch of solid colour which needs to be flat and pristine every time, that unleashed the demons of painting for Turk: “The frame is almost like trying to paint the glitch in the matrix, sort of like trying to repeat something that shifted around just slightly so that you can see things like the more obvious modernist references”. The fluidity of oil paint and its propensity to change as it dries renders painting, for Turk, an act of constantly composing and recomposing slippery, unstable elements that are at once familiar and new. The result, in Kerze, is that the history of art – stark modernist planes of colour and the innocent still life of the everyday – is then laid bare in a surprising way.

The departure from Richter comes in the fact that Turk’s candles have their glowing flames replaced by a meandering plume of smoke, locating them just at the edge of their utility, transforming them from something life-giving to a something in the throes of death. But this is more than a device to distinguish the Richter Kerze from the Turk Kerze; it is an existential comment on the smoke itself, which Turk sees as “an unwanted element. It reminds you that this candle is putting lots of wax vapour into the air that you’re breathing, that it’s actually contaminating the air”. He is searching for the other side of the candle, the dark underside that we normally do not consider when bathed in its warmth and light. “It’s romantic in a strange way”, he says of the whirling, curling smoke, “but it’s probably romantic because it’s a bit deadly”.

There is an interesting continuity between these paintings and Turk’s sculpture: his famous bin bags – painted bronze renderings of black bags full of rubbish in strikingly lifelike form – search for the beauty in the quotidian rubbish bag as a sculptural object. Similarly, the Pollock paintings are on a quest to turn a well-known icon of modern art on its head, to touch it with a hammer as with a tuning fork to see if it sounds of bloated entrails, as Nietzsche said. Pollock’s paintings, whatever incisive and florid things we can say about them, do not really mean anything or have any formal content to them, but Turk is asking the question, what if it did contain something meaningful – the signature of a real person – as the very fabric of its composition?

The idea behind Kerze is to reframe the candles, reform them, sculpt them into something else so that we see the yearning underside. When the candle burns, all is well and nobody really thinks about it, but it is only when it is snuffed out that we contemplate the candle in itself because without the fame it transforms from something beautiful to something stark, almost ghostly, a cipher of itself. This viewpoint is alluring precisely because it is existentially uglier, more portent with the ordinary anxiety of being human, and ultimately gives access to something more truthful than the swish, gleaming surface of contemporary art normally allows.

Gavin Turk: Kerze, Ben Brown Fine Arts, London, 03 November 2022 – 14 January 2023.

I have worked as a lecturer, teacher, bookshop manager, gallery invigilator, curator and freelance writer, for the most part simultaneously, which exemplifies a lifelong passion for art, culture and ideas. I was born on the Isle of Wight in the very year that both Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation and Arthur Danto’s The Transfiguration of the Commonplace were published.