[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]T[/dropcap]he exhibition ‘AMERICA’S COOL MODERNISM’ is showing at the Ashmolean from 23 March – 22 July 2018 again placing that epoch which we are apparently long since over back into the spotlight,

“The Ashmolean’s fascinating survey of American art in the era of Gatsby is full of images of emptiness and nothingness shot through with sudden moments of revelation. The artists are all trying to make sense of the modern world. Are human hopes vanishing in a bleak new landscape of factories and skyscrapers? Or is there hope of redemption on the mean streets?”

There is a kind of nostalgia for Modernism especially in America since in coincided with American early 20th century and post war domination, the reference to Gatsby from the Guardian’s Jonathon Jones also reminds us of the opulence and self regard associated with that time. Having explored modernist architecture in ‘Do We Understand Modernism? We Better!’ we asked Natalie Andrews to re-visit the subject in anticipation and coinciding with the Ashmolean’s show.

________________________________________________________

Modernism’s Inception in the 19th Century

Modernism is a broad term which refers to changes in attitude, intention and method across a range of disciplines in the arts and also in other areas such as philosophy and social organisation. The term then is really referring to a period of time and the tendencies, fashions and impetus driving western society at that time. The origins of Modernism are in the 19th century, ‘modern life’ as we know it today was coming into being as the great shifts in the way people lived and what people expected from their lives began to alter dramatically.

Notably this included the onset and development of the industrial revolution which not only saw a total change in how things were produced but also greatly increased the population of cities which became the destination of ordinary working people seeking a more prosperous life in the new factories and businesses emerging there,

‘Who among us has not dreamt, in moments of ambition, of the miracle of a poetic prose, musical without rhythm and rhyme, supple and staccato enough to adapt to the lyrical stirrings of the soul, the undulations of dreams, and sudden leaps of consciousness. This obsessive idea is above all a child of giant cities, of the intersecting of their myriad relations,’ Charles Baudelaire, 1869 ‘Dedication of ‘Le Spleen de Paris’

Baudelaire’s description is extremely optimistic he conflates the creative process of composing poetry to the architecture of the major industrialized city, it’s not that Baudelaire is not aware of grime or suffering in the slums, or of the crimes that big cities of his time bore witness to, but simply that he sees these new environments as being places where people could live and perhaps more importantly think in a modern way since he sees these environments as giving birth to modern thinking. People mix and are exposed to new phenomena in this context the modern subject is developing.

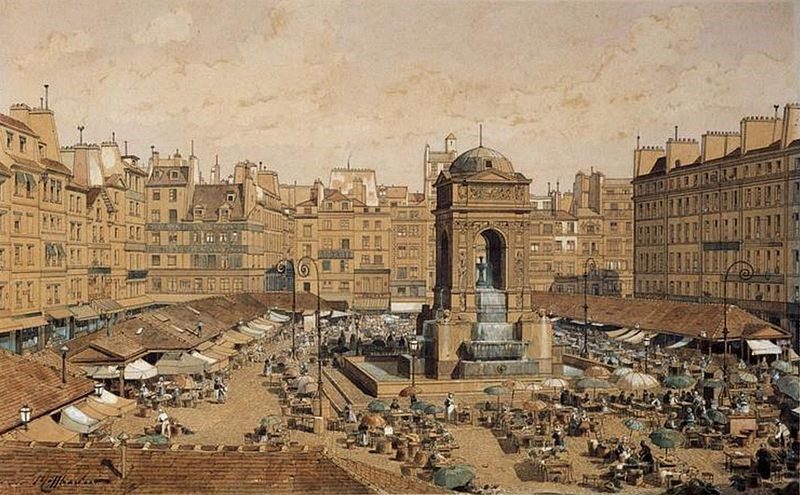

Saints Innocents in Paris, 1850. Engraving by Hoffbauer.

We see depictions of this world with the Impressionists, taking their inspiration from the Realists and from Manet they rejected the accepted subject matter, myth, history or aristocrats and instead painted everyday life capturing people and places in a new and fresh way.

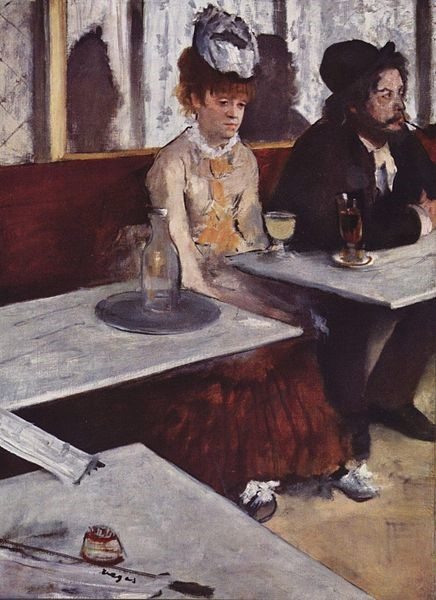

Edgar Degas, L’Absinthe, 1876, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

In Degas, ‘L’Absinthe’ a modern couple are seated in a café, the distant forlorn expression on the woman’s face is another very modern phenomena, boredom. People experienced a huge increase in free time and while many individuals must have succumbed to the same fate as Degas young woman this increase was giving rise to a new audience seeking ways to amuse themselves and, key for Baudelaire, with the time to consider abstract ideas that art and poetry could offer.

‘For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world—impartial natures which the tongue can but clumsily define. The spectator is a prince who everywhere rejoices in his incognito. The lover of life makes the whole world his family, just like the lover of the fair sex who builds up his family from all the beautiful women that he has ever found, or that are or are not—to be found; or the lover of pictures who lives in a magical society of dreams painted on canvas. Thus the lover of universal life enters into the crowd as though it were an immense reservoir of electrical energy. Or we might liken him to a mirror as vast as the crowd itself; or to a kaleidoscope gifted with consciousness, responding to each one of its movements and reproducing the multiplicity of life and the flickering grace of all the elements of life,’ Charles Baudelaire, “The Painter of Modern Life”, (New York: Da Capo Press, 1964). Orig. published in Le Figaro, in 1863.

Gustave Caillebotte, (1848–1894), Paris Street, Rainy Day, 1877.

The scene above in Caillebotte’s painting is immediately recognisable the couple depicted could be Baudelaire’s ‘flaneurs’ experiencing the city, we can see ourselves in these early moderns, we can imagine stopping for coffee talking about the events of the week and perhaps taking in an exhibition.

The idea of taste and sophistication is also important the notion that, familiar to us, that one’s free time activities are as important for developing identity as work or religion. The people depicted are surely the patrons, supporters and intended recipients of Impressionism for example, like the little cluster of people behind Courbet (hero of the Impressionists) in his earlier painting ‘The Painters Studio’ these moderns are lined up opposing the old order a cluster which included not only the anarchist Proudhon and wealthy businessmen but also Baudelaire himself.

The Painter’s Studio, L’Atelier du peintre A real allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life 1855 oil on canvas painting by Gustave Courbet

Baudelaire is on the far right looking down at his book. The opening created by the modern city for ‘modern’ thinking and the onset of new technologies which grew this opening by pulling more and more people to work and live in these environments had created the circumstances which would give rise to modernisms early champions, people like Baudelaire or the Impressionists, the idea of Avant-garde experimental work which is not restricted by habit or tradition is born and an audience with the time and inclination to pay attention, a modern ‘subject’ is also developing.

The next instalment: The Avant-garde (20th century)

Natalie Andrews is an artist working with a range of mediums, she has shown her work at the Hoxton Arches in London and is currently working on a number of 3d works alongside painting exploring the links between painting and sculpture;

“I am interested in the way that we relate to one another and with space, how the environments we inhabit structure and dictate these relationships and create both opportunities for emancipation but also the deep alienation and separateness.”