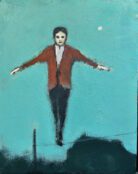

That’s the crux. In an era of personality painters, we have a painter who connects on a personal level without imposing his personality, and yet whose painting is wholly about his perspective. We are indeed party to that artists’ mode of thought, beyond just what he saw. The idea isn’t that we see exactly what he saw, now framed, but that he’s giving us a real experience of being. A glib appeal when written down but what happens on the canvas is remarkable, we are compelled towards the bellies of space in his paintings, pregnant perspectives that gives us weight in the scenes. Something impossible to convey in the flat voyeurism common to bad art and regular photography.

What is the difference between figurative painting and photography? Isn’t it all about representing what you see? The question of how and what the artist’s eye renders in their mind and transmits to the canvas is a deep and personal one. The basic answer is that the inspiration of the artist is more encompassing than the visual experience of photographic representation. And more to the point isn’t art less about visual representation as it is about the conveyance of meaning through artifice?

This is the defining characteristic of the perceptual painters school who investigate the relationship between figurative, realistic painting, what the eyes, and techniques that aim to break the painter away from traditional modes of working. Somewhat ironically painter Peter Van Dyck might be the strongest example of the movement and yet perhaps the loosest adherent. His work is resolutely his own and in it’s purity feels at once quaint and then truly apart. The curve ball in his work is that given the suburban subject it comes across as definitely unique. How did an artist working through a movement, from a classical background manage to capture a live essence? But it’s the case. Van Dyck’s work has power and allowing us to feel his work on its own terms, without his history, counts.

Born in Philadelphia in 1978 Van Dyck studied painting and drawing at the Florence Academy of Art in Florence, Italy from 1998-2002. Returning to Philadelphia in 2002 he began exhibiting in Philadelphia, New York and San Francisco. He has had solo shows at John Pence Gallery, San Francisco in 2004; Eleanor Ettinger Gallery, New York, 2006; John Pence Gallery, 2008 and The Grenning Gallery, Sag Harbor, 2010. In 2003 he began teaching at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts where, in 2011 he became an Assistant Professor in the Certificate/BFA program. In 2012 he was named one of 25 Important Artists of Tomorrow by American Artist Magazine. In 2013 his work was included in the book Painted Landscapes, Contemporary Views by Lauren P. della Monica. His work has also been reproduced in periodicals including, American Artist Magazine, American Arts Quarterly, Art News, American Art Collector, International Artist Magazine and Art and Antiques.

What is your relationship to perspective?

Most people think that perspective has to do with drawing straight lines as in architecture, which means that you are seeing any set of forms from a particular viewpoint. Now, when we talk about linear perspective, what most people take for granted or maybe don’t understand is the way in which linear perspective corresponds to vision. It doesn’t really but when Brunelleschi (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filippo_Brunelleschi#Linear_perspective), did his little experiment, in front of the baptistry, he was doing a little piece of virtual reality. He was isolating that tiny little part of the visual field where the rules of perspective are so close to optics that you could almost trade it out, but that’s because what he had done was taken the curve of the eyeball, he had taken such a small section of the curve of the eyeball that was so close to being flat, that it almost didn’t matter.

It is called the cone of vision and the arbiters of taste say that it’s 60 degrees. But you can take a little piece of tube and isolate 60 degrees of your vision and you couldn’t get up the stairs with that much vision. I have this experience of how something is when you look over there, even without moving your head, but just moving your eyes around, 60 degrees of vision is nothing. It doesn’t touch what it is to be somewhere. And so what I’m trying to do is to stitch together the elements of a macro picture. A wider, realer perspective of space which is a macro picture of the space. Whenever you see the world you’re creating this macro picture of the space and then you’re constantly forming these sort of sub pictures in a way that allows you to perceive it as this whole solid entity. But it might change the perspective of one thing compared to another thing, or the scale of it.

Is it playing with the telescopic nature of attention?

Yes, that’s exactly what it is. Exactly. And it’s a sort of gradual, incremental logic, things that are this big, then these things are this big, and things are this big, because every attentional moment creates its own picture your attention creates a different relation between things. I can look at my printer and I can swear to you, I can see my whole printer from here. And I can experience its solidity and all that stuff. But then when I look at just a part of the printer my perception is shifting to all these different areas. The phenomena of what you see creates a different space.

I’m looking at this just double storey space that just seems to be exploding, I can feel its bigness. And there’s a way to paint that bigness. Then there’s also all of these other subplots, big and small happening. There’s practically no end to how you might perceive all of that, and then how do you orchestrate that? And how do all these big pictures and small pictures weave into each other and all that.

So for me if the ordinary is a single shot perspective, which to me has no gesture, it goes in one direction? It keeps your head static essentially. And when you start to move that picture plane through which you envisioned, whatever it was that you were initially looking at, is now tracking with your attention. So basically, every time you’re moving, you’re creating this internal sphere, or the inside of the sphere. And so now if you to really simplify it, you could say there are these different sets of separate perspective pictures. Except that some of them are huge and some of them overlap in this way. Some of them are a little tiny ones, some of them stitch up something much bigger. And that’s how I conceive of it, but there’s no straight through logic to it.

The difference between what I’m doing and Cubism is that the artists were moving in their case. I’ve kept myself in the same place. I’m trying to use a macro spatial integrity, a space frame that everything sits in. If you picture a three dimensional coordinate grid basically, do an X so the static regular perspective just has things sit in some relationship to that grid, it’s okay. But my feeling is that once you start to move your head, you’re actually taking that grid and you’re sculpting it, you’re sculpting that grid, you can bend it here and tighten it there and stretch it in order to get it right. That’s why it ends up a weird trippy thing because I don’t know how else to do it.

The last thing I’ll say about that is that though I paint things that people don’t consider to have a gesture in them, people don’t think about perspective as gesture, gesture is the thing that’s happening. The viewer is implied in those gestures, and so the paintings have movement. The movement is that of the person painting or doing the looking as opposed to the movement of any particular thing depicted.

Thinking about bay window goggles (2020), like many of my paintings I start them from the small drawing. Because if I’m going to set up and really control what I’m doing, what happens is that the drawing will get very regularised because in order to translate this big experience to this canvas, I have to set up some sort of system of translation. And that system, any system, is automatically not interesting, because it’s a system. What I find is that if I walk around with a sketchbook and react to the space with little drawing, then what happens is, I get something very different as a seed. It plants a different seed than if I were to start with this big canvas. And so that’s where the weirdest stuff comes from. I get the most surprising stuff from this little drawing that is unencumbered by the constraints of having to set up the canvas or having to remember if this was here or there. But I take that seed very seriously. And it’s as important an (to observe that drawing) observation as anything else that I might observe because it’s an honest reaction to what I’m seeing unencumbered by other practical concerns. And so that’s where I find the gestural life gets discovered and then I will do my best to hang on to that oddness because over time what happens is that things will tend to calm down. I want to keep the benefit of it really stewing over a long time but maintaining the surprise of the process spontaneously responding to forms.

The light sources in your paintings would suggest early morning or late afternoon. Is it the shadows cast at that time that interests you?

That’s funny. It’s more practical than that I’m afraid. Though I love painting in the winter because you always get that nice cut. I would love to paint earlier in the day or later in the day, but it just can’t fit it in my schedule. Maybe when my kid is older, and I’m not doing stuff like teaching. I’d love to be able to start at four in the morning, and then sleep for part of the day, but that just doesn’t fit right now. I could make my painting seem to be done at other times but there are qualities of light that you have see. The light always is the motivator for painting.

Would you say that over time you’re building up a really deep vocabulary of these local places you’ve painted?

No, that’s the thing.

Because every slight shift of framing or every different sequencing is a whole new thing. I could isolate my whole career to this one little table that I have there. If you’re playful enough and curious enough with how you perceive things, or how you could perceive them, or how you could paint them, then it’s really never ending, there’s no end to the number of games that you could play. It’s a little bit like how somehow people still make pop music. Hasn’t it all been said already? Is there anything left to say? Apparently a lot.

Read more in Trebuchet 11: Process

Featuring: Samuel Andreyev / Ed Atkins/ Nairy Baghramian / Phyllida Barlow / Peter Van Dyck / Oli Kellett / Tae Kim / Chris Levine / Gisela McDaniel / Paul Sietsema / Jeff Muhs

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle