[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]A[/dropcap]rt and authenticity.

With the advent of mass-produced art, for some buyers the idea of having an original has less draw than you’d imagine. An original work is worth more, and it probably should be worth more. But if the message, meaning, intentionality and impact of a work on our eyes is unchanged, does it actually matter?

If a work has been reproduced to such an extent that it is not obvious to us that it is any different, should we care? If the copying of an artwork diminishes the value of the original by undercutting its availability as supply then perhaps we shouldn’t reproduce artwork in any fashion, however it is commonplace to have reproductions of work in almost any medium from coffee cups to calendars.

Of course, if someone is sold something as being of a certain providence and it turns out it isn’t then it’s a fair cop. However if a gallery is presented with an artwork by an ignorant seller and suspecting they might have a bargain in front of them offer a nominal sum, then who is to blame?

There is a delicious frisson in the idea of forgeries. The idea that someone can create a work that gets one past the gatekeepers of a private industry has a sort of Robin Hood appeal. Great artworks are usually owned by the rich and powerful, and the production of these works is largely done by ascended artists who are themselves rich and powerful, or famously dead. It also attacks the idea that it is only right that the rich and powerful own such works. There is a possessive symbolism to the production and consumption of art that is marked by a seemingly innate judgement which few possess and even fewer are able to exercise, with the exception of a few plucky brigands and the law.

Speaking to the BBC, Vernon Rapley, former detective sergeant head at the art and antiques unit of the Metropolitan Police and now at the V&A said of forger Shaun Greenhalgh:

“[Greenhalgh and his accomplices] had a resentment of the art market and wanted to prove they could deceive it.

Shaun Greenhalgh felt he was a better artist than he would ever get recognition for and developed a general hatred of the art market and the art establishment.

I think with all of these things it was the provenances that sold them. Looking at them now I’m not sure the items would fool anyone, it was the credibility of the provenances that went with them.

There are far better artists in this world than Shaun Greenhalgh and far better forgers but I’ve never come across a forger able to do that many disciplines, that’s what made him so exceptional and accomplished.” (Kelly, 2007)

The key thing to note from this description is that it at once praises the resourcefulness of the forger and yet denigrates his talent. Greenhalgh is painted as a bitter artist angry at his betters who managed to get away with it for only as long as his work was supported by canonical references. The provenance of artworks being an authority at the core of the art class, great works like aristocrats relying on birthright rather than their actual merits. Whether or not the artworks Greenhalgh copied were actually any good is up for debate. James Cuno of the Art Institute of Chicago maintains that Greenhalgh’s (via Gauguin) Faun is “both a good sculpture and a crafty concept” having been compiled from artist sketches and exhibition notes (Vogel, 2007). In all cases it is the production of truth and value that is put on trial, the discovered forger in Greenhalgh’s case merely the punishable body.

In 2010 the V&A displayed a collection of forged work by Greenhalgh, John Myatt, Robert Thwaites, John Andrews and Peter Ashley-Russell, including the shed where Greenhalgh created many of his forgeries. The works shown would have at one time been worth over £4m.

“This display demonstrates that art crime is not just a topic for historic consideration.

“We hope that by highlighting some of the new techniques criminals use, we can educate people in what to look out for and encourage greater reporting of these crimes to police.” (Rapley in BBC, 2010)

However the story is far from over for Greenhalgh.

Between 1989 and his discovery in 2006 Greenhalgh produced a large number of forgeries successfully selling his work internationally to museums, galleries and private collections. In a reversal from the normal trajectory of creative producers in his case one of his most intricate pieces—The Amarna Princess, bought by Bolton Council for £440,000—was revealed as a fake resulting in his arrest. Since then he’s been the subject of a BBC drama in 2009 titled The Antiques Rogue Show and has published A Forger’s Tale: Confessions of the Bolton Forger (Allen & Unwin, 2017) to sett his story straight, from his perspective at least. Do we believe he’s reformed? Does it matter?

After being hidden away for a long time, how are you finding your celebrity status?

It’s been more or less positive. I’m rather surprised; I expected a bit of flack for what I’ve actually done, you know, committing a crime.

I’ve had quite a few letters. They’ve all been positive which I’m surprised by. I’m not proud of what I’ve done, I’m not a boasting kind of person, and I never set out to do it. It’s very hard to explain. It kind of just happened without any plans towards it. I think it’s strange myself when I look back on it.

You’ve claimed, and it’s been disputed, that you did La Bella Principessa by Leonardo da Vinci in your twenties.

Yeah, in my teens actually. I’ve had quite a lot of doubt and disbelievers, and that’s fair enough. It was strange at first; someone started sending art books to my current address, and this particular thing, I opened it and saw the picture and thought that looks familiar, but I’d done so much stuff I wasn’t sure. The clincher for it was the old back, the butterfly braces. I knew then it was absolutely mine. I even went to Milan, it was on display there. I just went out of curiosity and there it was. It’s been quite restored from what I did, there’s been a very good hand that’s improved it, but the basics of it are my work, that’s just the way it is.

How many works do you think you’ve done?

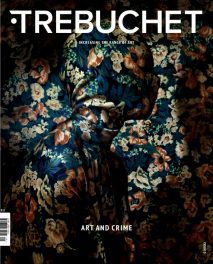

Read this article in full in Trebuchet 5 – Art and Crime

Trebuchet Issue 5 Art and Crime

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle