Marcus Rees Roberts is an intaglio print artist, a painter, a film-maker and a writer. He studied English at Cambridge, where his dissertation was written on Elias Canetti’s Auto-da-Fé. After graduating he studied film at the Slade School of Fine Art, writing his thesis on German Expressionist cinema. He subsequently pursued a second post-graduate degree in printmaking at the Slade. He has since taught at the Slade, at West Dean College, and at Edinburgh College of Art as Head of Printmaking.

His work is held in the collections of The British Museum, The Ashmolean Museum, The Victoria & Albert Museum, University College London, Blackburn City Museum, The Scottish Arts Council, The Sackner Archive, Florida, Pallant House, The Muzeul Florean, Romania.

I

This exhibition ― This Dark Shore ― at Julian Page Projects brings together various strands of his work. The gallery is a large airy space and the show is very well put together, accessible, engaging and beautiful; not despite but precisely because the themes are darkly poetic, even mythic. ‘The hang’ of the prints is particularly apt. Uncovered by glass, the prints are pinned to the wall and this gives their physicality pronouncement. It is difficult to resist feeling their surfaces; and it accentuates their diurnal character ―as if the glamour of fine art has climbed down from its pedestal.

Recent work in aesthetics has led in two opposing directions. On the one hand, everyday aesthetics encourages the view that the ordinariness of experience can be bracketed out to reveal the sheer beauty of the quotidian – the way in which a torn edge might be more lovely than a scissor cut, or an edge mark on a rough print might enhance the beauty of a print. It’s the ‘everyday-ness’, the roughness, that makes it beautiful in face of the professionalism of the paper-cut or the obsessively neat wiping of the edge of the plate.

Here is Rees Roberts writing in Printmaking Today, on Otto Dix’ print series Der Kreig, now 100 years old and worked up from experiences and sketches undergone in the trenches of World War I:

“As I opened the solander box and saw the first prints, I thought of Bakhmut. I was also surprised at the somewhat rough editioning: the uneven plate tone; unfiled bite-marks at the plate edge and smudges of ink where one expects a seamless transition from plate to paper; the ink from deep lines smeared. It looked as if the making of the plates and their printing were done in a hurry. And probably they were.” (Printmaking Today, Vol. 32, Issue 128, Winter 2023, p. 10)

He ends that piece writing,

“The fighting in Bakhmut is relentless and attritional, often in trenches reminiscent of the First World War. A Russian or Ukrainian soldier fighting in Bakhmut would recognize [Otto Dix’s] images as chillingly contemporary.” (p. 13)

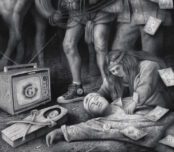

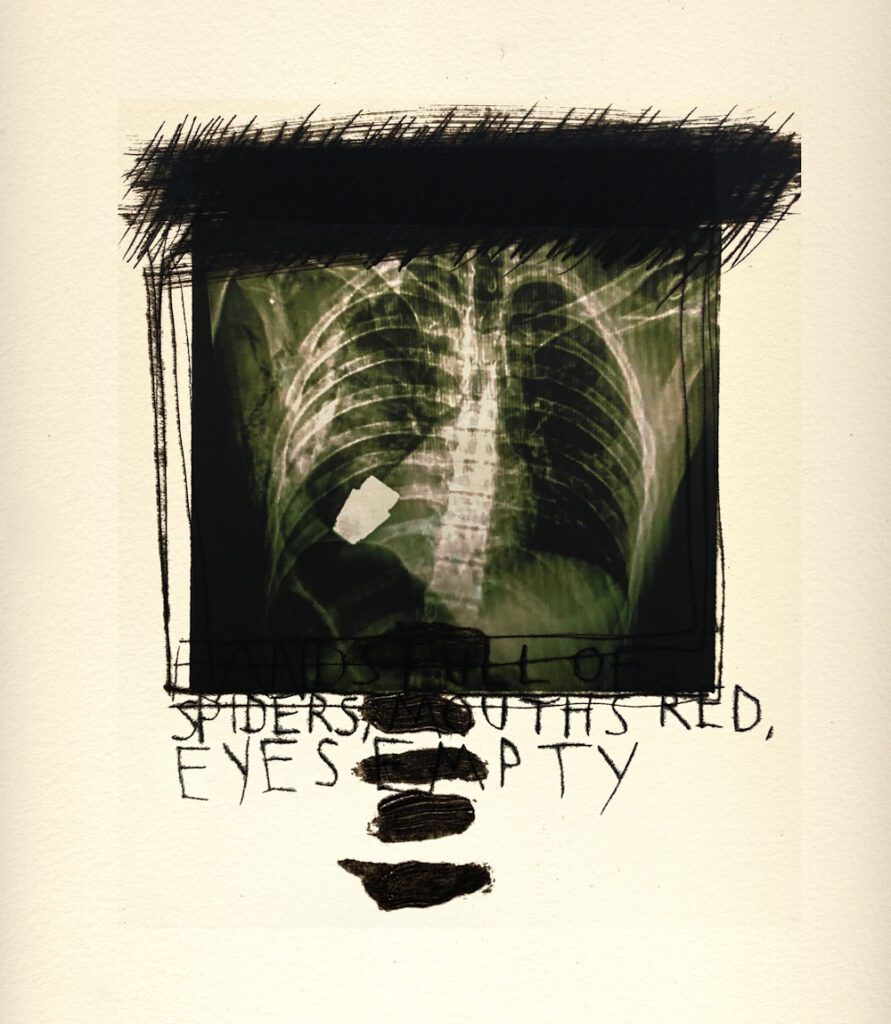

The realism is what startles us. For those fighting in the manifold theatres of the present world, these are ‘everyday’ experiences. It is something to make such beautiful work out of such desperate, dismal, delinquent hardship. But is this not what the great religious images of old were there to illuminate: our wretched condition?

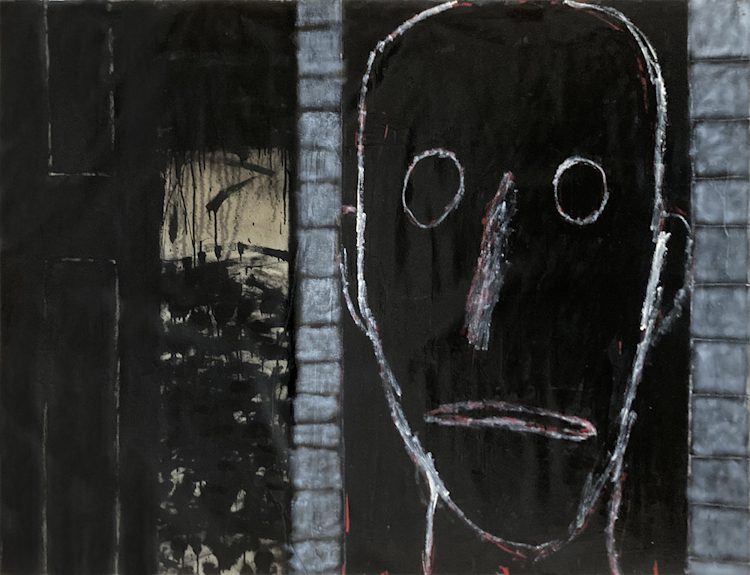

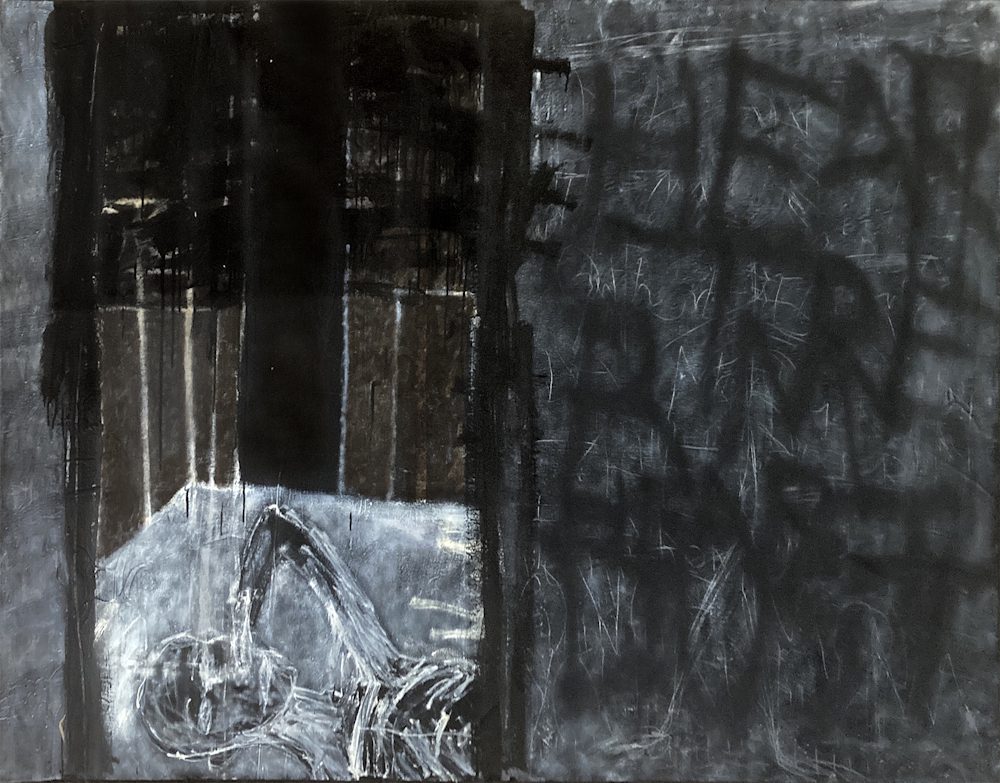

The work has matured over the years. Early on, Rees Roberts’ work was commentary upon the state of narrative, with references to narrative and its opposition, Brechtian ‘anti-narrative’. He brought to the Slade a wealth of literary theory from Cambridge. To his dismay, it was striking how such theory was beginning to be introduced to the visual arts at the time. Increasingly his work has come to focus on the solemnities of this life for those less fortunate. It has become a non-religious mythical narrative, even as some of the images use religious references. One set of prints, A Stabat Mater, is narrated around images of the deposition of Christ (He is privately collected by a Roman Catholic priest). Nevertheless, these prints contain images of the pliers or pincers that would have been used to prise the nails from His hands and feet; and another has the ladder that would be climbed to release His corpse. One thinks of Martin Heidegger’s distinction between the ‘ready-to-hand’ and the ‘ready-at-hand’. The former is the normal use of something like a tool (Heidegger uses the example of a hammer). The latter is used when a tool is broken so that the carpenter, for instance, considers the tool he cannot use. In the case of the ‘ready-at-hand’ the thing becomes estranged to him ― a thing to cause puzzlement.

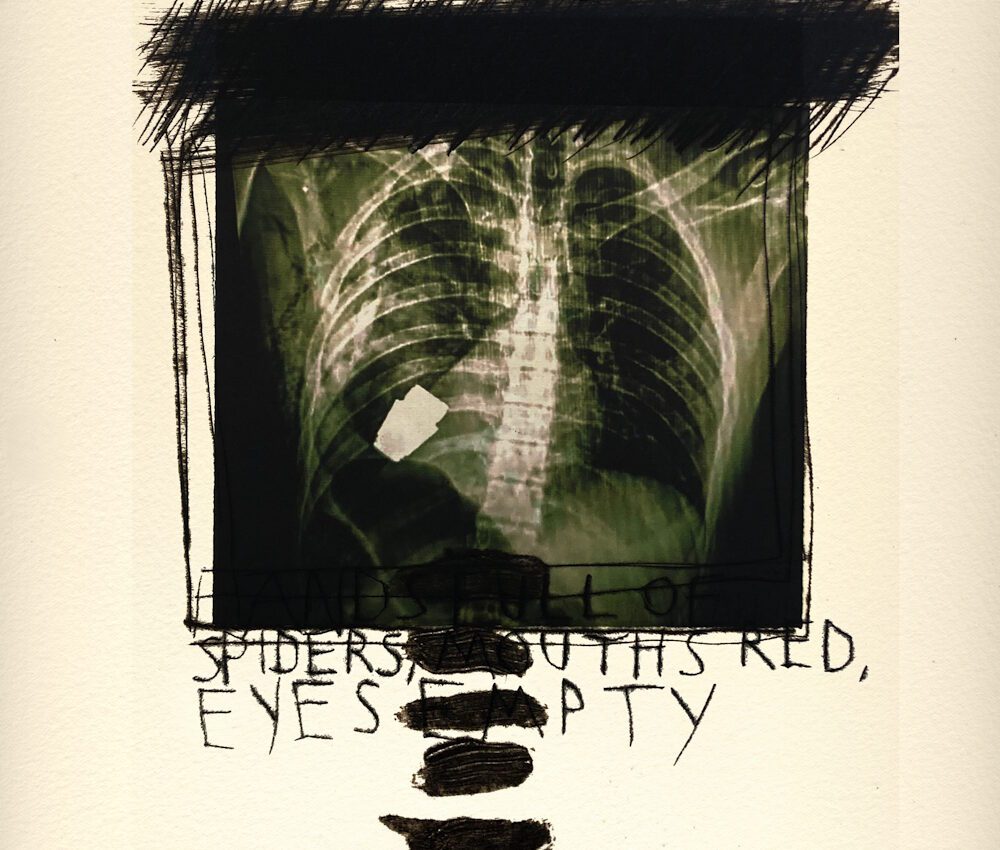

Thus, the sinister image of pliers, of scissors and of a knife; of a hand-grenade floating in a space with its shadow beneath; of two faces in confrontation. Enduring throughout the oeuvre is a sense of removal or alienation. We look from this world into another. Again this reminds us of the religiosity of art’s history ― its use of art to illuminate texts; or the use of myth to educate and to explain what is, in essence, ethereal ―beyond our understanding but yet brought into our imaginative lives. That brings us to a second directional tendency in contemporary aesthetics.

II

Almost, as if in contradiction to the everyday aesthetics tendency, is that of a recommitment to the medium specificity of the fine arts. Dominic Lopes has argued against those who see the avant-garde as free agents, unrestricted in terms of any medium specification. Instead, he argues for what he calls the buck passing theory. It is this theory that he reckons best explains all art-kinds. Asked if Robert Barry’s Inert Gas Series, 1969, is a work of art, Lopes argues that we must ask to what art-kind it belongs. He goes on to argue that it belongs to the art-kind, Conceptualism ― hence the buck is passed from art in general, to that particular art-kind. In his book, Beyond Art, O.U.P. (2014) he attempts to formulate the medium specificity for conceptualism. Whether or not that is successful, he reopens the possibility of thinking through art-kinds as a way into understanding their examples.

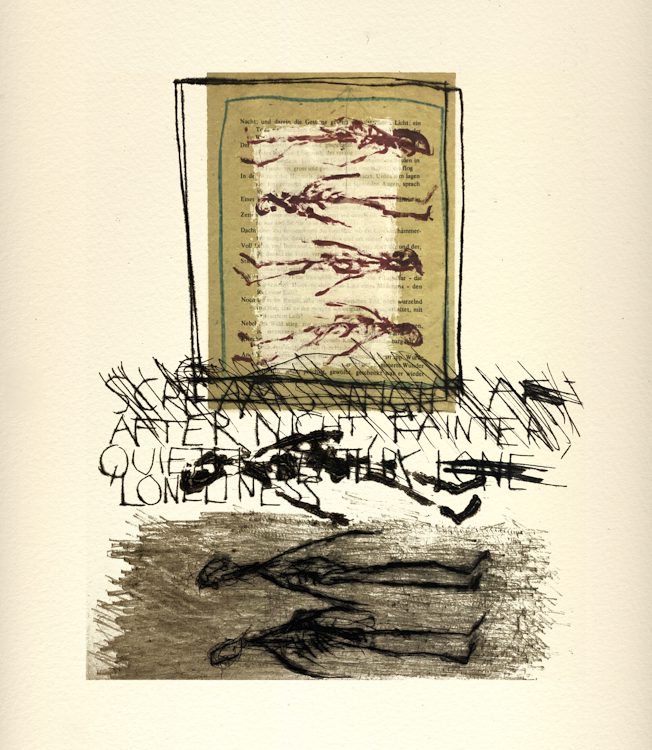

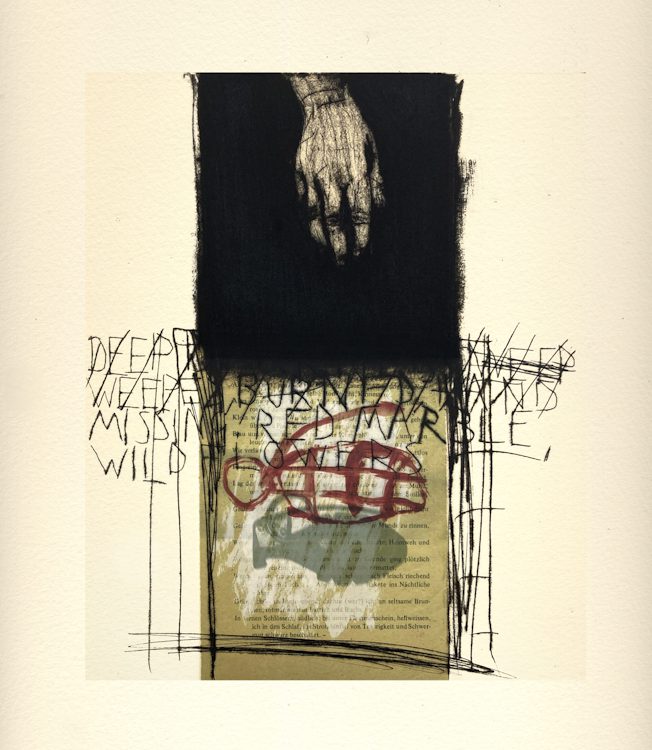

Some art-kinds have shared specificities as well as individuating specificities. So, Painting, etching, sculpture and architecture all share the specificity of drawing. Whereas each has further individuating specificities. Rees Roberts is a master intaglio printer and painter. His prints, as well as etched, include drypoints, papier collé, chine collé, aquatint, sugarlift, photo-etching and collage. He also works, in print and in collage and painting with inserted materials, such as the pages of books or with written text in a childish scrawl as might be found upon graffitied walls. This, too, harks back to modernist tendencies. As Christopher Green notes in his Art in France 1900-1940, Yale (2000)

“Apollinaire made the following observation. The object in such works ‘constitutes the internal frame of the painting, marking the limits of its depth just as the frame marks its interior limits’ (…) At that moment in March 1913, the poet-critic pinpointed two factors newly introduced into painting which were to have devastating effects: the object and the word.” (p. 128)

Notwithstanding the range of media used by Rees Roberts, it is easy to see how this effects not only painting but also other media in which the introduction of material objects and of the written word can limit the internal space of the pictorial. His extensive knowledge of intaglio print permits the use of textures too, adding another layer to the print as an object. The picture has literal depth – that between the face of the plate and the bitten areas, where the blackness opens a cavernous space into which a sparse light gives a muffled edge to the shapes of things.

Hence, we read words, or even partial words which limit the depth of his pictures and we find ourselves with internal poetic, almost Beckett-like, minimalist murmurings which act like shadows playing across the picture plane:

CAW, CAW, CAW (…); ECHO. DUST. THE DUST; SNOW YOU SLEPT

These shadowy meanings are interspersed with overshadowed shapes of letters that lie just beyond legibility. It is a simply excellent exhibition in a beautiful new gallery space.

There are two paintings which relate to Portbou, the small Spanish town on the foothills of the Pyrenees, where, holed up in a small hotel, being chased by Nazis, the Jewish thinker Walter Benjamin knew he would be denied passage to proceed across Spain to Portugal, from whence he might take a ship to the USA. Benjamin took his own life in that hotel. Rees Roberts remembers, as a boy, making the journey, by car, down through France and then to Cadaqués. Portbou must have seemed heavy with redolence to a young man falling in love with Catalunya. The paintings are dark reminders of the days in which Benjamin tried but failed to escape.

This Dark Shore is at Julian Page Projects, 12 Northgate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 1BA

11 Sep – 1 Nov 2025

Images courtesy of the artist and Julian Page Projects

Monday to Wednesday: by appointment; Thursday to Friday: 11am – 4pm; Saturday: 11am – 2pm; Sunday: Closed

Bibliography

Apollinaire, Guillaume. Quoted in Green, Christopher. Art in France 1900-1940. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000.

Green, Christopher. Art in France 1900-1940. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. [Original work published 1927]

Lopes, Dominic McIver. Beyond Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Rees Roberts, Marcus. “Otto Dix: Der Krieg.” Printmaking Today, Vol. 32, Issue 128 (Winter 2023): 10-13.

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.