Rune Christensen (b. 1980) emerges as yet another artist claiming the world as his canvas. His work, ostensibly inspired by “the process of living,” presents what has become a familiar trope in contemporary art: the artist-as-nomad, collecting cultural souvenirs.

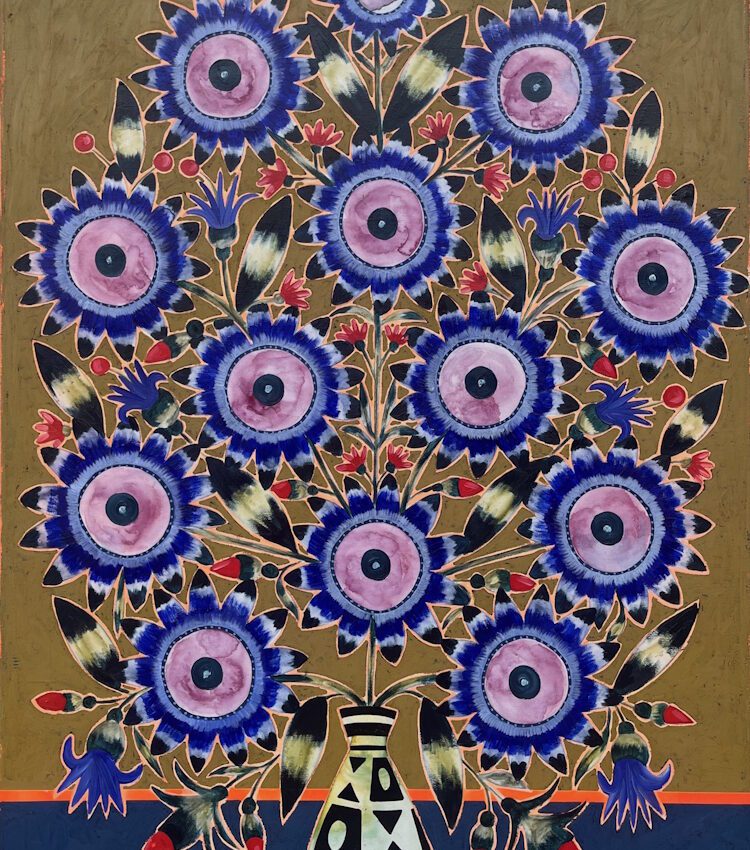

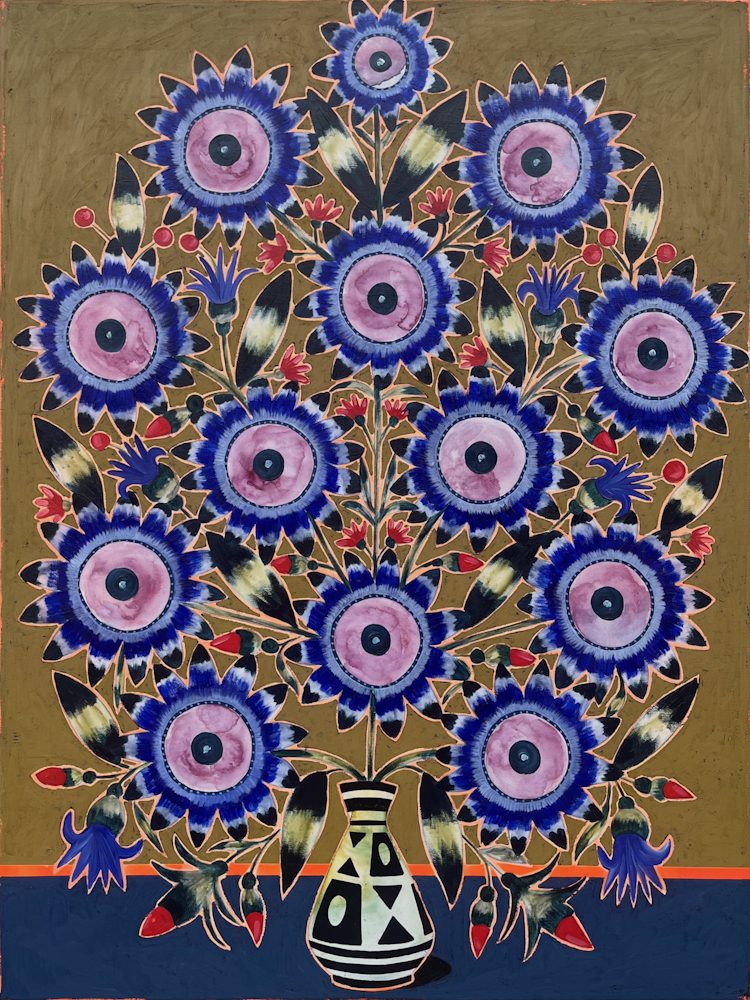

Christensen’s art offers viewers what a hotchpotch of global impressions—raising questions about the line between cultural appreciation and appropriation. His paintings, described as “intensely overwhelming” and “excited,” risk prioritizing aesthetic spectacle over substantive engagement with the diverse contexts they purport to represent.

Yet perhaps this is precisely where Christensen’s potential lies. As his work shows an evolution beyond mere collection of visual experiences toward a more reflexive practice—one that acknowledges the complexities and power dynamics of patterns underlying all our lives—his rich life is translates into rich art. The melting pot he creates becoming not just a spectacle of difference, but a thoughtful meditation on connection in our fragmented world. One rooted in an appreciation of our surroundings, the foreign experience of us witnessing the domestic.

In this interview with Trebuchet talks to Christensen to understand why his process is touching the universal and from where those cardinal points emerge.

Your work has a strong geometric composition. Can you talk about that?

Rune Christensen: That’s a good question, because it’s something that I don’t really consider much. I just do it because it satisfies my understanding of how things should be in the chaotic world of my mind.

Most kids start painting and drawing early on, and then most people stop. A few of us are fortunate enough to continue having this as a hobby or profession later in life. I was lucky to find graffiti in the mid-90s. Graffiti is very much about repetition of pattern and color. If you’re doing a piece of graffiti, you’re putting an arrow over here, and then you repeat this arrow over there to create movement. That’s part of why I paint the way I do.

I was listening to this podcast from Headley Roberts, a British artist and professor, and what it left me with was the idea of finding your inner child—why are you doing what you’re doing? When I was doodling as a kid, and later as an adult when you’d sit and doodle next to the phone, it was always patterns, triangles and circles. I’ve always been very intrigued by patterns.

During my travels, a lot of the inspiration from past shows has been about moving around the world, seeing and absorbing. I bought textiles—I’m just very drawn to them. So that’s how I end up with these compositions. If I put something over here, I should put it over there to balance it out. It becomes this repetition of things.

I’m very interested in tapestries and weavings from medieval times in Europe, and from all over the world. There’s often a story in the middle, and then there’s a flower here, and a flower there, and a flower here, and a flower there. And somehow it satisfies my mind. I don’t know why it ends up like that, but it’s hard to explain.

So it’s a textile/craft influence?

Very textile, very inspired by textiles, especially from my travels. It was very interesting—I was in Xinjiang province in China, and the Uyghurs there all wore these special hats. They were green and had patterns on them. The hat would tell a story of who your family was, what your profession was, what your dad’s story was. I found that fascinating—communication through pattern.

We’ve been doing it here in Europe as well for hundreds of years. The Vikings were tattooed, that’s what we think. We don’t fully know because we don’t have a tattoo from a Viking, but all research points toward them being heavily tattooed. One of the oldest finds we have is Ötzi from Austria, a 3000-year-old shaman who was found frozen in a glacier. He was tattooed, so we know some of the oldest tattoos are 3000 years old. He had different tattoos that probably communicated something, again, through patterns.

I find it really interesting that we can wear something that tells who we are, and we still do it nowadays. You can see if somebody’s from Scandinavia—we have a certain way of dressing. We have a certain look. The same goes for Germany, Holland, and so on. We’re part of a tribe based on what we wear.

That’s a cultural, symbolic dialogue, I suppose.

I was really fortunate that as a young man, when a lot of kids—especially boys—stop drawing and painting around the age of 12-14 because they worry about looking cool, graffiti came along for me. This was before internet and magazines. I watched “Wild Style” on TV somehow, and I was listening to KRS-One who talked about graffiti on the CDs I bought.

I started tagging, and then an older boy from my small town approached me. He’d been at a boarding school where he met some graffiti guys from Copenhagen, and he brought graffiti to me. Then we started painting together. That allowed me to continue being a mark maker, because that’s essentially what art is—you have some kind of color, a brush or pencil or spray can, and you attach it to something.

For ten years, graffiti allowed me to continue painting instead of being a young man who lost his creativity. For me, it was graffiti because it was macho and cool—if I was doing my flower paintings at that time, I probably wouldn’t have been considered as cool.

So I was wondering, is there actually any connection between graffiti and the flower paintings you’re currently doing?

I don’t think I have any direct connection to it, but anything you’ve done in your entire life becomes part of your habitus, part of the backpack that you carry. It will always be there.

When people talk about inspiration, especially when you’re making a solo show as I’m doing right now, it can change from day to day. I ate a burger, I listened to some music, there was something on TV, somebody said something, I read a book, I saw something in a magazine—it all changes. Inspiration is such a poor choice of word for what it is. Everything is inspiration. Everything that happened to me in the last week will go into a painting. Maybe just 0.1%, but it’s there.

It can sometimes be one-to-one, but the other tricks in the bag, or the other lifetime that you lived, will always be in there. Even if you’re looking directly at a David Lynch film or a political problem, I will never be one of those painters who can say, “Oh, this is from this specific thing.” It will always be what’s around me and what I’m experiencing, and what I can draw on from other experiences. It’s going to be a big mix of what’s going on in my life.

I always work in series—I’ll never just make one painting of something. I always continue because I feel you need to make a certain amount of similar imagery to get to know what you’re actually doing. If it’s a one-time experience, you’ll never get to know it properly.

Broadly speaking, your paintings settle in to a few distinct categories: flowers, interior still lifes, and forests, plus some amalgamations of people’s faces. Can you talk about this evolution?

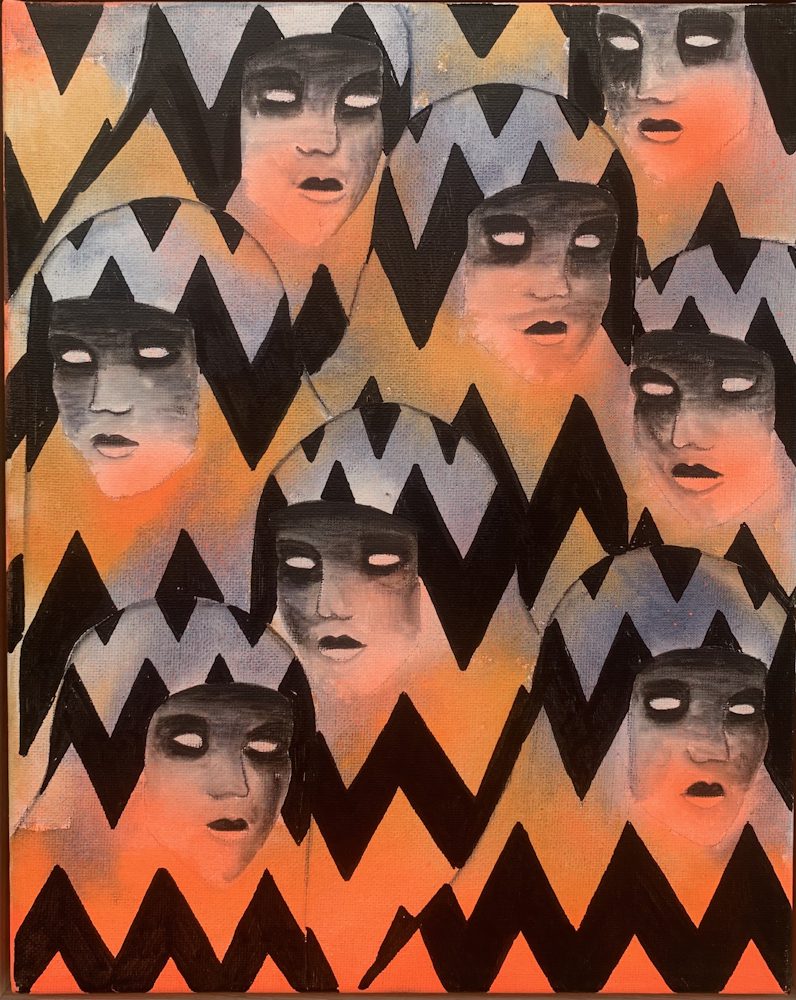

The multiple faces—I have one hanging right there—that doesn’t really happen anymore. That was a two-year period when I was working in that kind of style. I did a show with Kristin (Hjellegjerde) in London with those paintings. Then I worked and changed them up a little bit, and I was done with that story.

That was part of me moving away from the city. Those paintings were about moving through multiple people, multiple cultures. I lived in a very multicultural area in Copenhagen, and I was also traveling and seeing all these people. They became almost like a carpet of information that you can’t really fully fathom—what you saw, who you met—but you remember that they were there.

Then those disappeared, and I went into tigers and snakes and tiger fights. That was about balance—I moved from Copenhagen to here, and it was about figuring out how to be a new me in a new setting, a father again and a provider for now two children. How do I balance that out? That drew on my travels in India, Nepal, Tibet, and other Asian countries, where the tiger and the snake are very mystic and sacred animals.

Then came the flowers, because I’ve always been very interested in vases and flowers and what they represent in both human history and art history.

And this is in your ‘still life’ pictures, I’m referring to pieces like “Collected Memories” and “Anecdotes and Keepsakes.”

Those paintings, especially what I’d call the shelf paintings, came about similar to the paintings with multiple people. I enjoyed this idea of a carpet of information that I gathered by living. Before it was humans, and now my life is more about going into the forest and picking up pine cones with my children, or bird feathers, or plants. We do mushroom picking in season.

It’s essentially going into this environment and collecting memories and physical objects and taking them home. My daughters have these little collections of seashells and things in their rooms. My house is essentially full of things that I’ve collected.

The painting “Late September” is so named because we grew sunflowers with my kids. We would start nurturing them on the windowsill, and then plant them in the garden where they’d grow up. By late September, they’re amazing, and then they start falling apart.

So I thought about the art historical still life—a bouquet in a vase. But then I considered: what if I zoom out? What’s around it? Oh, it’s on a shelf system. On that shelf system, I have markers over here, a picture of my daughter there, and so on. So it’s about zooming out and thinking, when I pick up a flower and put it in a vase, where does that come from? It comes from the forest, which connects to the forest theme I’m working with now for my show.

It’s like seeing a carpet that has that same feeling as the painting. That’s what I was searching for—the weaving. It has that same feel, but it’s not humans. You have a flower, then you zoom out and that flower is in a vase, then you zoom out and that flower is on a shelf, then you zoom out and that flower is on multiple shelves. You can view your life a little bit that way—here’s a problem, where does that problem come from? If you zoom out, maybe you can see it originated somewhere else.

You’ve got three-dimensional aspects, like the perspective on chairs and tables, but things still have a flatness to them. What’s the importance of that flatness?

I’m not relating to any technical light painting or realism. It’s just the way that I express myself. It’s like asking Bob Dylan, “Why does your guitar sound like that?” And he’d say, “When I pick it up, that’s just what comes out of it.”

I’ve always been drawn to color, pattern, and repetition. When I see paintings, that’s what I look at—multiple mediums, multiple stories, lots of color, lots of interaction with the canvas. That’s what I go for.

If I really go back to when I started understanding art, it was through Asger Jorn, a Danish abstract painter who’s now deceased. He used multiple colors, thick layers—that was my first interaction with art that I remember. My dad taught me about him. Then some years later came graffiti, which is essentially what Jorn was doing—multiple colors—but in graffiti, we frame it off and organize it.

That’s what I still do—my paintings will have a lot of colours going around, compositions and shapes and things everywhere. Then I start breaking it down, controlling it. That’s what my life is and has been—lots of chaos, and then I’ve got to sort it out. Pay that bill, call that friend, make the meal, go for a run.

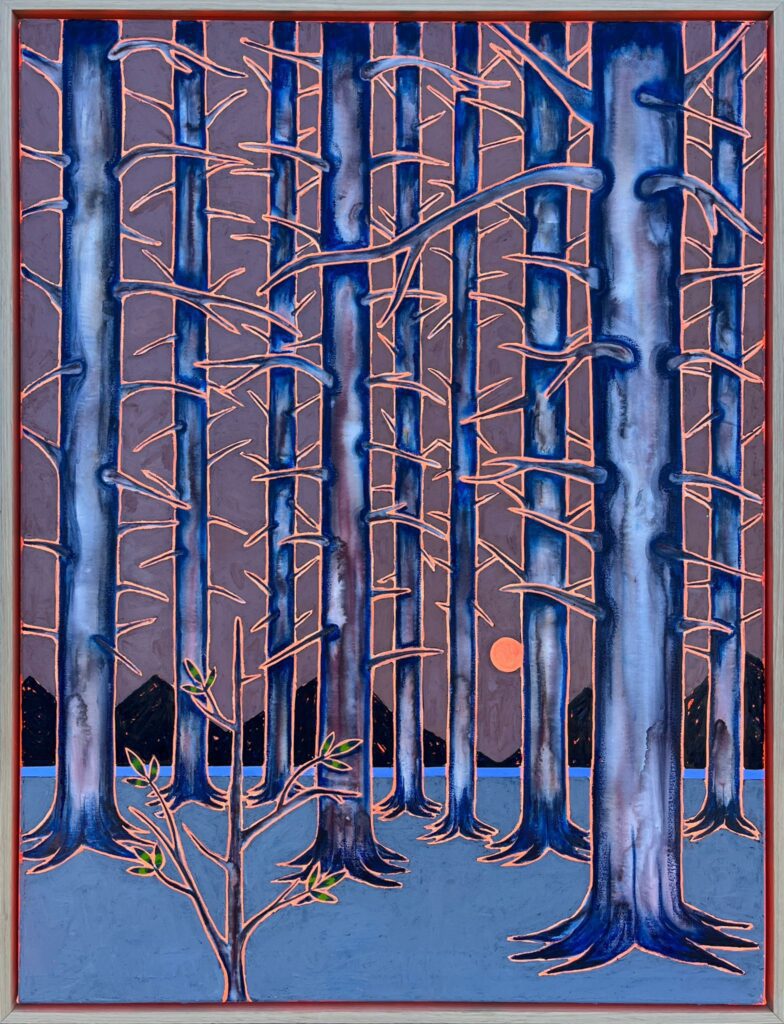

There’s quite a contrast between the simplicity of something like “Alberta,” the wealth of information in “Anecdotes and Keepsakes,” and then “Beneath the Canopy,” which has almost a moiré effect with tree trunks slicing down. Is that your barometer—knowing when something is working based on how the triangles on the vases create energy, or how the distinction in “Beneath the Canopy” gives it that Rousseau flavor, but with heavy Scandinavian trunks instead of jungle wildness?

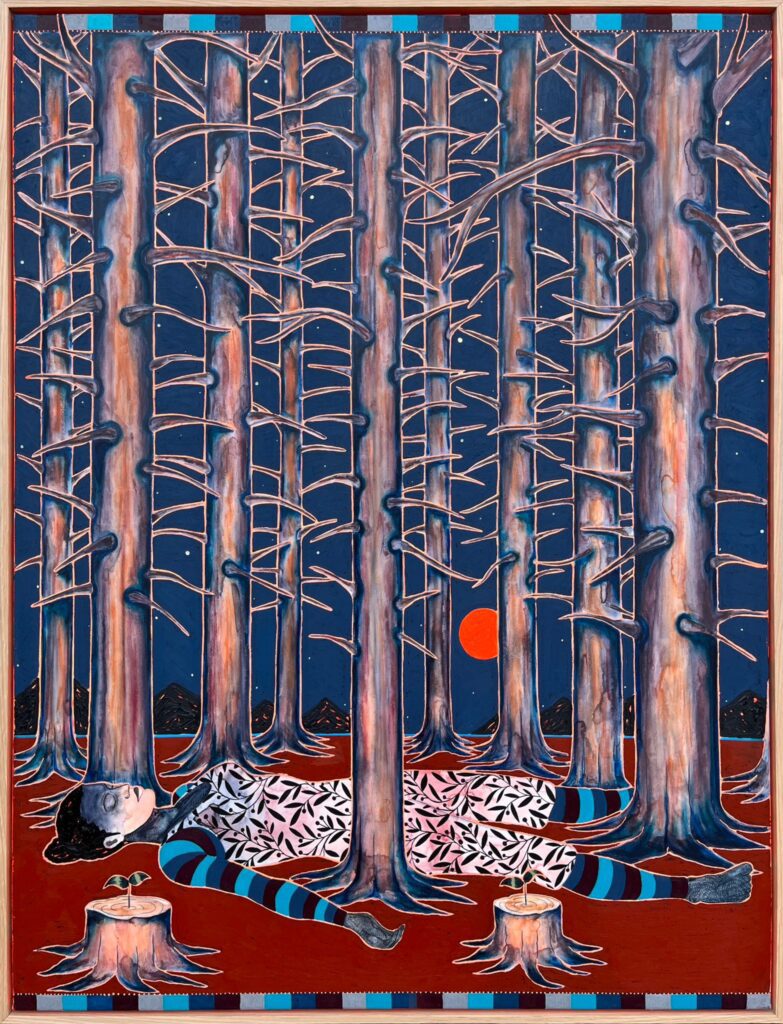

Yes, that’s exactly what it is. If you take it from the paintings we’ve been talking about from the last show, “Amass,” then “Beneath the Canopy” is moving toward my new show.

[At this point, Rune shows several paintings of forests]

These are clearly not done yet, but these are pine forests that I visited on a trip with my kids. We went out to see these trolls that have been built—you can go hunting for these big, massive wooden trolls in Denmark, and they often have a swing or something. It’s really cool. It’s in the same forest where we go mushroom picking.

“Keepsakes and Anecdotes” represents the collection of objects, and now I’m zooming out again. Where do these emotions and memories come from? They come from me rediscovering the magic of the forest, which is where I grew up playing. When I was a kid, I grew up close to the forest. We would always go there with my friends. We would make bows and arrows and whatever else. It would be magical—I remember hunting for whatever we were hunting for down this creek, with spears that we made.

Now I return to the forest as a dad, and I get to see my daughters venture into this amazing space. If a parent is fast and good enough at it, within two minutes of entering, we are on this great adventure of magic. That’s what this new show is about—me rediscovering the magic of the forest.

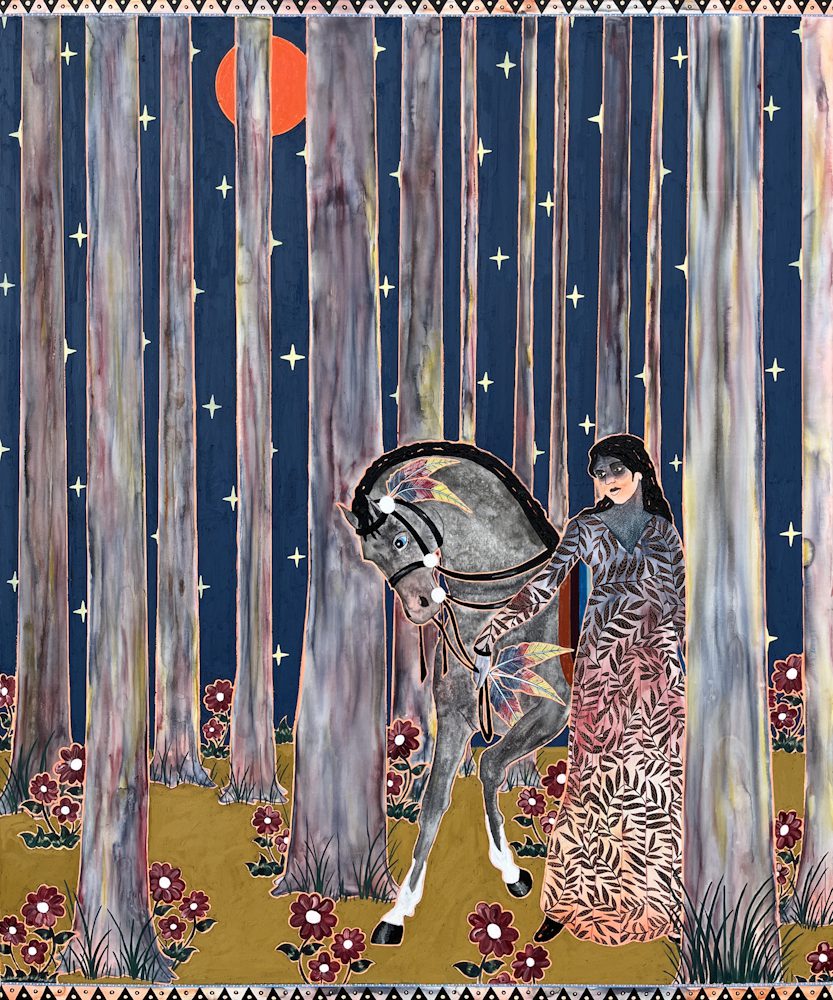

Some of the little motifs in those paintings remind me of medieval or quasi-medieval fairytale paintings—the shape of the horse’s head and those sorts of things.

That’s what I’m doing right now. Every night, I read to my kids for about 40 minutes. I’m looking at very naive approaches to illustration. Then the next day, I’ll bake some buns and take them into the forests, go to this creek and throw some rocks in, or collect moss or mushrooms.

That’s my life now. Before it was tigers and snakes and Asia and traveling all over. Now it’s becoming a very small life with fewer destinations. Before, my life was, “Let’s go to India or Canada,” flying around, doing things. It’s very sheltered now, with fewer destinations, but as my friend said, “You get to rediscover the magic of a worm.”

When your child finds a worm and says, “Dad, look at this worm!”—you’ve seen a million worms since you were a kid and normally wouldn’t care, but suddenly it’s cool again. That’s what fatherhood and motherhood give you—your inner child comes out again. There’s a lot to gain from that as a painter, because you get to play again, which is what we’re doing when we paint. We’re essentially just playing.

Reading children’s books brings a lot of magic—they are essentially magic. That’s where the inspiration is really coming from, observing these little humans growing. When we go into magical spaces like a forest or a beach, it’s amazing how many hours kids can spend digging holes in sand or tunnels in snow, or searching for mushrooms in a forest. Children who might normally ask, “Can I watch some Netflix?” at home—that doesn’t exist in those spaces, because it’s magic to be there.

Rune Christensen, Beneath the Canopy

19 September – 25 October 2025 Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, West Palm Beach

Read more in Trebuchet 17: Destinations

Yang Fudong – China’s Foremost Artist?

Manifesta 15 – Message received?

Sandra Knecht – Redefining home

Art in the Margate – Escape or reality?

Art in Copenhagen – What to witness

Aesthetics now – After theory, now what?

Rune Christensen – Fairytales and tradition

Tarek Atoui – Improvised Sound Installations

Outsider art and the new devolved

Chris Levine

Profile: Sarah Hilliam (National Portrait Gallery)

Rune Christensen is represented by Kristin Hellegjerde Gallery

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle