Mary Kelly, Face-to-Face, solo exhibition, installation view, Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London (2018)

[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;]M[/dropcap]ary Kelly’s Face-to-Face exhibition engages its audience with work that is at once intellectual and experiential. One enters the Pippy Holdsworth Gallery on Heddon Street in Mayfair to read printed on to the wall,

“To be in relation with the other face-to-face is to be unable to kill. It is also the situation of discourse.” – Emmanuel Levinas

The Search for Freedom

At the conclusion of the second world war, Paris set about re-thinking its freedom and how life might be lived after a state of intolerable repression under occupation by Nazi Germany. Simone de Beauvoir points up a difficulty to be faced by humanity’s search for freedom. Jean-Paul Sartre, her partner and editor of Les Temps Moderne, asked Beauvoir to write an article for the review concerned with the condition of women. Beauvoir responded by writing “Women and Myths”, published in 1946. That piece opened with the sentence, “He is The Absolute, and she is The Other.” The essay was developed by Beauvoir and became the seminal two volume work, The Second Sex, the first volume of which was published in 1949.

Beauvoir is credited with providing the philosophical foundation of second wave feminism. “The Other” has subsequently been used to identify groups of people disenfranchised by patriarchy; and so includes women, people of colour, homosexuals, transgendered people, those persecuted for their religious beliefs, people born with or accruing disabilities, the homeless, and so on – the disenfranchised.

The Turn Against Expression

It is laudable that conceptual art, reacting to the aestheticism of Clement Greenberg, should have sought to give voice to such otherwise silent communities. No longer expressing the angst of the artist as a solitary seer, the artist is engaged in social concerns and does her best to address them in ways that articulate that which is otherwise passed over.

Mary Kelly is such a conceptual artist. Indeed, in turning against the subjectivity of art, she was apart of a movement that licenced artists to adopt and adapt everyday issues as part and parcel of the work they had begun to make. For feminist artists like Kelly, this meant taking the daily routine and turning that social fabric into her narrative art.

She became famous for exhibiting the stuff of motherhood and the clutter of domestic life. Her son’s nappies became the material of her output. Such an adaptation of the everyday also permitted her to take teaching on as an extension of her studio work – rather than as a necessary chore to be borne in order to afford studio time.

Later works used pressed lint as a medium. The lint is discarded fabric and human detritus collected after many thousands of cycles of her washing machine which collects the lint in rectangular pads.

Mary Kelly, Scarcity: Untitled #1, 1966, magazine photographs, various colored drawing papers, mounting board, 64.8 x 63.5 cm, 25.5 x 25 in.

Face-to-Face

The show at Pippy Houldsworth contains work from the sixties as well as new work. The earlier work shows her at a stage anticipating the revolution that convulsed the artworld in the seventies; although, even this work shows an appreciation of social philosophy, a move away from subjectivist expression. The latest work now shows how content has developed since studio project work abandoned the traditional forms of art-making; and how new material forms have become part of that content.

In the 1966 series of collages, Scarcity, Kelly comments,

“I (…) was prompted by my first encounter with the work of Sartre, specifically his concept of scarcity as the foundation of violence and man’s inhumanity to man. Using magazine photographs, colored paper and chinagraph in starkly minimal compositions, the works represent my reflections on the Vietnam War as well as the broader context of poverty, imperialism and resistance. Shown here for the first time, they provide an insight into the very beginning of my career as a project-based artist concerned with themes of social justice.” – Mary Kelly

Perhaps it is the fear of scarcity that has filled many westerners with confusion, muddling up refugees with economic immigrants and demanding national borders closed. Perhaps, that is, we could repel all boarders so that we need not look into the eyes of refugees in flight from scarcity and repression. Such an internalisation of social justice relieves the burden of regarding international social justice as imperative. It funds the idea that a nationalistic “We” is confronted by an alien “Other”.

In any case, the works Kelly made in the sixties look as fresh today – and as relevant – as they would have done back then.

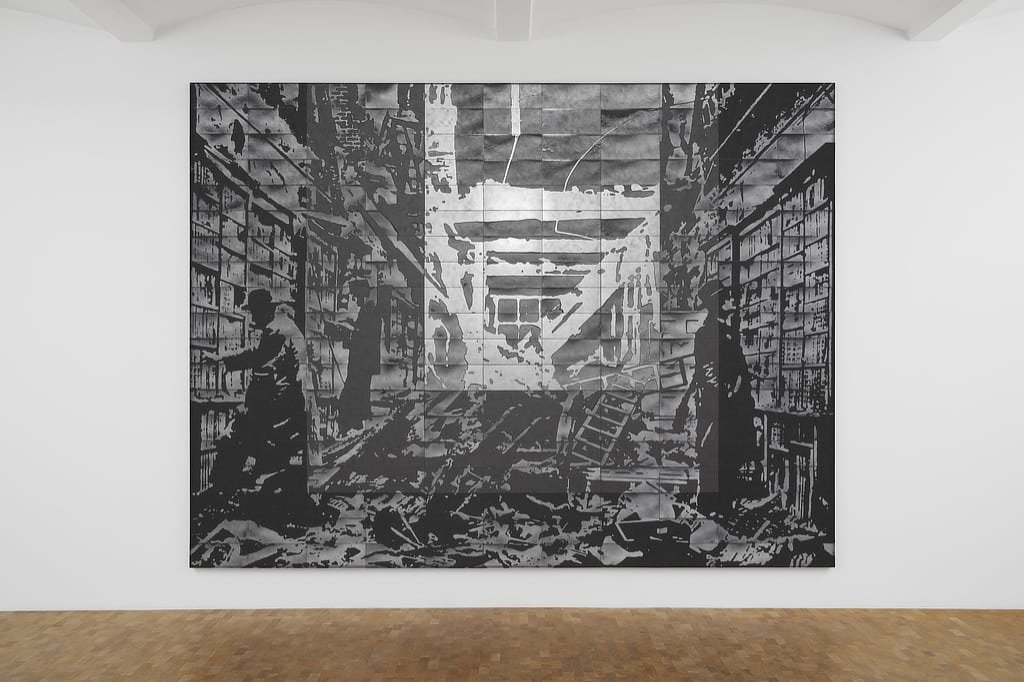

Mary Kelly, Circa 1940, 2016, compressed lint and projected light noise, 242.6 x 322.6 x 3.8 cm, 95.5 x 127 x 1.5 in.

Of Circa 1940 (2015), Kelly tells us,

“[The title] refers to a photograph commissioned by Fox Photo Agency during World War II. Taken on October 23, 1940, one month after the Blitz began, it captures the devastation of Holland House Library in the aftermath of a Luftwaffe raid on London, but the subtext is one of reassurance. The Library, which was part of the private estate of Lord Ilchester, was sold to the London County Council in 1952, during the Labor Govern ment’s post-war construction efforts and at a time of growing opposition to the cultural legacy of colonialism.

I would describe this moment, not long before I was born, as the political primal scene for my generation, which links it to the anti-war protests of the 1960s as well as the Arab Spring.” – Mary Kelly

The image is partially projected onto a composite photograph, leaving a kind of static, familiar to those of us who remember black and white television and the graphic infirmity of newspaper photographs that would have been around at the time. Kelly refers to it, aptly, as “projected light noise.” The work shows the library and the chaos caused by the German bombardment, but, at the same time, contemporary readers in their wartime clothing stand browsing or reading the books in the library.

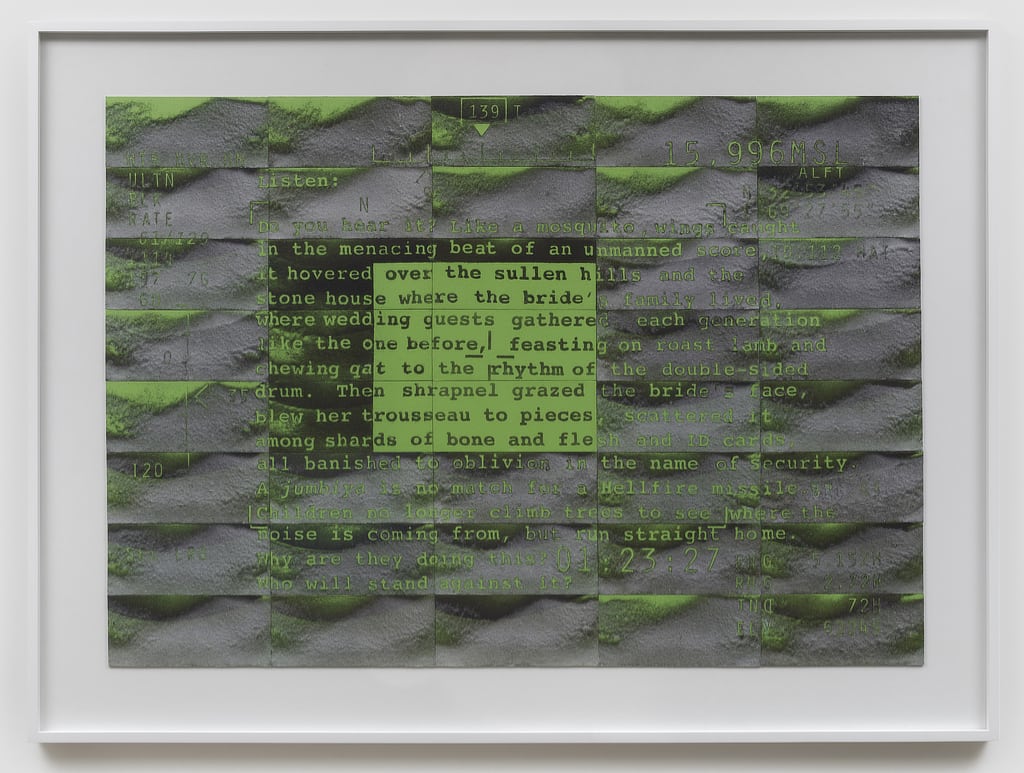

Mary Kelly, Dicere #2, 2018, compressed lint, mounted on card, framed, 101.6 x 146.1 cm, 40 x 57.5 in.

Dicere #2, (2018), is perhaps the most disturbing piece in the show. Possibly because it is grimly remembered by those of us who watched in horror as the television reports came in.

“[The work] combines the satellite transmission of a drone target with a narrative based on accounts by witnesses of a US Hellfire missile attack on a wedding convoy in which they were travelling to celebrate a cousin’s marriage in the Radaa district of central Yemen on December 12, 2015. For me, it was the distance from the scene, the absence of faces, that underscored the violence.” – Mary Kelly

Re-Kindling Difficult “Beauty”

This review essay began by making the (fairly) uncontroversial claim that the works of art comprising the exhibition are both intellectual and experiential. Greenberg’s formalist aesthetics tried to persuade us that an aesthetic experience, unencumbered by conceptual clutter, would give us the purest of unmediated pleasures. In this he failed to grasp the philosophy of art ingrained in Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgement.

Kant did not hold the formalist view of aesthetics Greenberg saddles him with. Rather, in the case of the fine arts, Kant thought of each as a dependent beauty – mediated, that is, by a determinate concept of what a painting, a poem, a sculpture, a work of architecture, and so on, is supposed to be. So, Kant has the concept of what an art kind is regulating the judgement from the start.

Of each work within one of the fine arts, we then have to see how it transports our thinking/feeling over an aesthetic idea that cannot itself be captured in mere conceptual terms. (We cannot transcribe a work of art into a merely linguistic description.)

As far back as Aristotle, philosophers have claimed that the purpose of art is not to replicate reality. Representation distances us from the real world and places us into the realm where that real world can be viewed in parentheses.

“[I]t is (…) natural for all to delight in works of imitation. The truth of this (…) point is shown by experience: though the objects themselves may be painful to see, we delight in the most realistic representations of them in art, the forms for example of the lowest animals and of dead bodies.” (Aristotle 1984)

“Fine Art shows its superiority precisely in this, that it describes things beautifully that in nature we would dislike or find ugly. The Furies, diseases, devastations of war, and so on are all harmful; and yet can be described, or even presented in a painting, very beautifully.” (Kant, 1987)

The success of the conceptualists, and of Mary Kelly in particular, is that difficult and terrible things in the world can be addressed in the art that emerged over and against formalist aesthetics.

It is a mistake, however, to think that works of conceptualism, in having renounced a certain form of aestheticism, are not themselves to be valued as aesthetic objects. It is, just because they are work of fine art, their beauty that makes them so moving and impressive; one would like to say, persuasive.

References:

Aristotle (1984), The Complete Works of Aristotle, ed. J. Barnes, Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 1448.

Kant, I (1987) The Critique of Judgement, trans. Walter S. Pluhar, Indiana: Hackett, §44.

Images are copyright Mary Kelly and courtesy of Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London

Face-to-Face is open until November 3, at Pippy Houldsworth, 6 Heddon Street, London W1B 4BT

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.