The curator Larry Ossei-Mensah has an ongoing mission to represent issue of race and colonialism that pushes the viewer beyond the sanitised paths of what we gloss as history. Controversially, some find his aggregations of colonial history too broad to sufficiently encounter the complexities that the history presents.

Equally, however, it might be argued that sometimes these totalising histories subsume the individual character of syncretic immigrant experiences into a statistical collective without hearing the details in personal stories. In which case, groups shows like Mensah’s allow us to feel the points of individual artists’ stories and to more fully gauge the weight of history’s pressure on current generations. Ideas that drag us, undertows that push us unwilling towards shores, made alien by the subjugations of race, class, time and direction.

Mensah shows us that concepts can time travel. When people think of colonialism, images of power, priviledge and oppression spring to mind; monarchs, manacles and money. Austere portraits, yellowed photos and reams of bureaucratic ephemera, travel and work papers, with names often transliterated into ‘their’ language. People and places transformed mentally and conceptually into an objectified frame of capital, from treasure to commerce to market capitalism ameliorated by the gloss of philanthropy and scientific enquiry. In many cases the method of colonial rule has changed however the rule of logic has not. The reification of colonial rule as ‘right, just, moral, scientific, healthful, beneficial’ and justified by testimonials and exemplary individuals, too often places itself above the idea of self-sufficient, and thus determinate, communities.

The global ties of market and wealth tie former colonies to their former rulers with bonds of education, legal systems, labour and medicine. Systems where global superpowers and their corporate classes have an overwhelming advantage and where the benefit to post-colonies is negligible in terms of growth and sustainability. Colonialism; has many faces but if it can be summarised as the flow of wealth and power from one country to another then it continues. Connected by labour, commerce and wealth most people are powerless within the relationship that defines their socio-economic environment. In a word; multi-nationationals.

Philosopher Timothy Morton describes the anthropocene as a conceptual overlay of the reality that prioritises the human perspective however as he and other proponents of Object Orientated Ontology suggest, this only one reality and that several competing ideas exist. As postcolonial journal darkmatter postulates;

“While [Object Orientated Ontology] can be critically illuminating, it hides as much as it reveals, and those who it hides are people – those subjects who have been treated as objects, or not-quite-subjects, or altogether other, or some combination of the many, all along, who have suffered the plural and particular consequences of the transformations and exclusions that capitalism – and thus the capitalocene – brings.”

Clearly the Thatcherite ideal of possessive individualism devoid of society and community is one where all actors consider themselves equal within the market – suffering is then not a function of the system, but merely the regrettable, and hopefully passing symptom of an actor’s unwillingness to function – rather than the modus operandi of a system endowed to create losers as a function of success. And yet within the cracks, hope forces its way through, and dimly progress prevails.

The voices that Mensah presents have their niche, defying even the curator’s efforts to present them as a contained narrative. Which isn’t to say Mensah’s overarching context is misguided when it works it presents us with the grey text to counterpoise the imperialist thrust of black and white pages. So how did he start to collate these voices?

Larry OM: It started when I was reading Kwasi’s book (Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng, Ghosts of Empire: Britain’s Legacies in the Modern World, 2010), and looking at how colonialism was structured. I read this book when it came out in 2010. And then, thinking about that in relation to the African diaspora and the Asian diaspora, I started seeing all these overlaps. So, to link to one your questions – what are the effects of colonialism? – I’m interested in this residue that’s consciously and unconsciously present. It gets everywhere. You think you’ve cleaned it? But it’s still there. And I think there’s been active work in terms of this, these ideas around decolonization.

You’ve worked with many disparate voices, can you talk about how a voice like Gisela McDaniel’s got to be heard?

We did a talk together for Art Basel last year. So Gisela is an artist, I used to be the senior curator, and located in Detroit, and Gisela was one of a constellation of artists that I met based in Detroit, who I thought were offering us a unique point of view. I had never met anybody from Guam. And to understand what it means that the US has colonies.

Funny enough, I did a show last year that explored this. And so the conversation felt fresh. She’s doing this out of Detroit, at the last place that I would expect this to emerge from, technically it felt different.

It’s been great. And, I guess, one thing that I encouraged her to do when she was in Detroit was to go back [to Guam]. Because a lot of times, depending on if you’re me, a first generation person, and if you’re making work about aspects of your cultural identity, some of it can exist in an imaginary space or some of it’s attached to a memory, and then you go back to the place, and you’re just ‘oh’. It’s like talking about your realities, but the reality is different. It’s a lot more nuanced than your eight-year-old recollection, as it was so for your 16 year old self… etc. And so, for me, I’m excited about using the resources.

I have to create a forum for these conversations and you go to a lot of these historic museums. I just saw the Winslow Homer show at the Met. Beautiful show. But a lot of paintings depicting his time in the Bahamas, but what did those paintings look like if it was a bohemian artist? [Was this really] someone trying to explore their own ideas? So it’s a Western take on history.

It’s okay. There are a lot of stories about these different parts of the world., perceptions and understandings. But what happens when we collaborate, and provide a forum for these artists who tell parts of their story?

That’s the difference with this show, it’s coming from a first person point of view. It was very mindful that we weren’t exoticising these cultures because it’s from a direct perspective. So this show will help me answer a lot of questions about how I see myself. How do I see my culture? How do I navigate myself by cultural identity? What does it mean to be American?

It’s a combination. So when we did the show in Hong Kong, for example, there was a picture of a Sikh amongst local Hong Kong citizens, a beautiful picture, but I had no awareness that the British sent Sikhs to Hong Kong to basically be overseers of the Chinese. Which obviously creates this tension. But it’s indicative of how colonialism functions: you take the minority, put them in power, then you create this natural tension with the majority. But that’s just a little sliver of history that people are going to teach me; unless I seek it out I’ll never know it. It’s so subtle. And it’s in the picture to ask a question, what’s happening in this? Why are these individuals oriented in this way? Take Paula Lael, her work is probably a little bit more confrontational about the Philippines as it confronts the colonial history in particular with the Spanish.

The messages within the show are quite nuanced. Do you want to make it explicit?

You have to be careful to get the balance right. The information definitely will be available if you come to the show and want to learn more. But also the difference between a museum show and a commercial gallery show is that, in the latter, you want to invite the viewer to have their own interpretation. Also normally gallery shows don’t normally have didactics, but there will be materials available for people if they want to learn more and understand what’s happening in the picture.

And then that’s why we’re also just trying to talk to as many of our friends in the press as possible – to share the varying perspectives so that they can begin to think about it. This is of interest to me, I want to see this and experience this. Because someone like Adam DeVore, for example, who’s Eurasian which is a new term to me. But using Batik fabrics, or batick techniques to make paintings – to me this is super innovative.

For me, when I can talk about the Indonesian Malaysian lands, I can also talk about that in this connection to Africa., connection to Dutch trade. And so it adds another layer of nuance that I find interesting. So it’s a balance of how much you spoon feed the viewer, but then allowing them to see things or even see themselves. I did a show in Miami, 2018, and it was artists from Detroit in Miami. One of the artists, who is South Asian, did a window vinyl, featuring someone. You can see it from the street on Lincoln Road. A South Asian woman came to me and said ‘I’ve lived in Miami 13 years, and I’ve never seen myself’.

Similarly, what does it mean to see aspects of your culture highlighted in the gallery setting in Mayfair, which is an upmarket area of London. So there’s still these ideas around visibility, which regardless of what the media is saying, there’s still a lot more work that needs to be done in terms of what museum collections look like and who gets access to this work. When a Giselle blows up, who are the buyers? Are they her people? Are they Micronesian folks? Are they people from Guam? So it creates this interesting tension. My hope is to ask more questions, or settings to ask more questions, because it’s not about nice neatly packaged answers.

You’ve got a thematic umbrella but doesn’t this suggest a hegemony of sorts?

It has to be a combination because that’s what Chris (Ofili) is- a great example of being British Nigerian, so he’s aligned with the Kami people and also British Nigeria. Then he’s also primarily based in Trinidad, so that takes on another interesting layer. Trinidad is obviously influencing the form of the work that he’s making now. This isn’t necessarily reflective in the show but it’s there in him as an artist. My aim was to try to have a broad cross section. So, while I’m focusing on artists from the Philippines and people with heritage from Chinese, Japanese, Korean, as with the book, I’m more interested in these trade routes because that’s the connective tissue that binds to the African continent, South America, the Caribbean and the US and Europe. Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s book, Ghosts of Empires, looked at Nigeria. Iraq, Burma, Hong Kong, etc.

Ghosts of Empires that was written in 2010 and the book explains how British colonialism structurally functions because in America we’re taught the Queen sent out these flotillas. They went and discovered these places, and then took them over. When, in reality, it was the governors who made all the decisions. They might have kept the Queen abreast, but it was the governors who ran things. Particularly if you look at a place like India. So Kwasi Kwarteng, who’s Chancellor in Parliament, wrote the book; it was this fascinating articulation of how it worked. And how it is still working.

The postcolonial ghosts that we live with make us question whether these places are truly free and the way that things are structured that, if they were to sever ties, there’s an economic implication to that. The book, for me, was a framework, I wasn’t necessarily just focused on British colonialism, I wanted Maya and Jeanne to give a Spanish perspective as well. Paul Anthony Smith was talking to me about breezeblock architecture in Jamaica, and how a lot of that is Chinese influenced. This amazed me and (these observations) are an attempt to go one layer deeper, but not in the way a historian would do it. That’s why the artistic perspective is interesting, because it’s the artists highlighting things they lived with, presenting the questions that they had (in context of their lives).

The goal is to show a cross section (of post/colonialism). I knew that I couldn’t represent these spaces in totality but if I could have a cross section, which spoke about the connections to the UK, and knowing that the show would end in London, it could work.

Part one was in Hong Kong from March to May (2022). The feedback was really interesting in that a lot of people said this is not the type of sh0w that typically comes to Hong Kong. And for me, given the climate, it was a way of trying to navigate their relationship with mainland China. It was an interesting way for them to look at themselves and understand their history in a nuanced way. Their push towards this more independent rule has been interesting to learn about. What happens when you have these other examples of thinking about the residue of colonialism? And what has been created in spite of it?

In the case of Paul Antony Smith, there’ll be images in this show from Notting Hill Carnival. There’s one particular image, it’s in the press pack, of people dancing on the bus stop. It’s a powerful image, knowing that these carnivals come out of an act of resistance in general. Also knowing that we still are dealing with the tension around the attempt to return Windrush generation citizens back to a place that is not home for them which is an attempt to deny their citizenship and participation in the rebuilding of the United Kingdom post World War Two.

There are subtleties in the work, which I find (reflect social truths) and the artists are pointing them out. So I wouldn’t say anything in the show was overt, rather it’s allowing space for people to have their own engagement. For example, Miguel Ángel Payano Jr has Afro Caribbean roots and was born in the Dominican Republic, but has lived in China for 15 years, went to grad school in China, speaks Chinese fluently and he’s now married to a Chinese woman. When I found all this out, when I got to know him, it confused me, it seemed so unusual. As in, how the hell are you in China and have managed to adopt Chinese ways and nomenclature? It’s fascinating that he’s able to articulate these Chinese cultural nuances from an Afro Caribbean lens.

Is that art’s ability to allow us to see another reality?

I’m more interested in its capacity to shift our understanding of our reality. In Ghana, there are certain cultural rituals that we observe, and I ask my parents what does that mean? Why do we do what we do? They’ll reply with something like ‘Oh, it’s just culture’. Now, I wouldn’t say there’s a lack of interest in getting into where it comes from, but shows like this one provide a forum to ask those questions: Where did this come from? Why is this normalised behaviour? And is this normalised behaviour appropriate? Is this normalised behaviour inclusive?

But then, yes, art can invite us to imagine other realities.Think about a genre like Afrofuturism, which comes with this idea of a black imaginary, but for me, I’m more interested in what’s the reality? To ask where is the information that has been omitted? The omission of information is a fundamental part of the postcolonial discourse because a lot of these colonial countries are doing a really great job of branding themselves. There’s an article in the New Yorker (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/08/23/britains-idyllic-country-houses-reveal-a-darker-history) that was a catalyst for me taking a wider view because initially I was going to focus on the African diaspora but then I read this article and it was about a lot of the castles in the UK going into disrepair and the illusions of aristocracy. This triggered something for me thinking about the book because at the time of British control of Hong Kong, you had an elite aspiring to these knighted titles. The book talks about this, about trying to increase your proximity to the Queen, and now the King, and what that means. Let’s face it, it’s still a reality now. However, it’s expanded as it doesn’t necessarily need to be ‘Queen’; (the idea of proximity) could be towards influencers of money. Anything that confers status by association. It could be all these different kinds of ideologies that people believe will give them validity as a human being. When,in reality, it’s all an illusion. So how do we question that? How do we construct our identities if not in relation to other people?

Now, my perspective is as a Ghanaian who grew up in America. I’m American but I will always lead saying that I’m Ghanaian first because I know that’s the place I can go back to. It’s interesting to talk to friends who are born in Britain, they’ll lead with ‘I’m British’ before ‘I’m Pakistani’ or whatever. They’re British before they’re Indian, or Nigerian, which I found interesting. It’s obviously everyone’s personal choice how they identify, but I want people to think about why are they not navigating this by cultural identity? Are you suppressing one thing in order for another thing to come to the fore? How can we celebrate both things? Because all of these communities have made a significant contribution to building what is here in the United Kingdom. It’s a win,perhaps with caveats isn’t always properly acknowledged but we know that that’s the reality.

There’s a piece from an artist from Vietnam who did a whole project looking at Senegalese soldiers that were sent to fight in the Indochina War, and then they took partners and moved back to Senegal. So you have a whole community of Senegalese Asian citizens. That’s an omitted history that blew my mind.

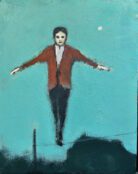

KING LOJHAR (AFTER TILLMANS), 2022

Are paintings the best method to communicate facts? Don’t we need facts now more than interpretations?

My hope is that the paintings invite us to ask important questions. I’m not necessarily interested in presenting answers because this is very complex and an exhibition is not going to answer those questions, but it can get you to ask more questions. Where’s this information coming from? How come I was not taught this in school? Do I agree with this? It’s not necessarily trying to be cookie cutter because that doesn’t make sense.

I made a decision a long time ago, particularly with group shows: not everybody’s gonna get it. But if you connect with something that invites you to ask questions, or ignites this fire in your belly when you see something that important, does this come from? Imagine people seeing this with a friend or a family, and then it starts a dialogue. For me, that’s success.

We can get into facts, but those facts are normally in a newspaper, in a magazine, a podcast, and the everyday Joe is not reading those things. And if they are, they’re looking for specific things around the economy, jobs, inflation. If you want to talk about this historical mission, colonialism, perhaps this is another (not the only way) of not just talking about it but having it talked about.

That’s the beauty of the community I’ve built. Since 2000, when I first came to London, these people live in South London, they live in Croydon, and they live in all these places and will come because I’m doing something in London and it’s inclusive. So my goal is also to attract a community that wouldn’t normally feel this was even for them. Interestingly this framework of my practice is something that I’m starting to articulate more formally.

Ghosts of Empire II – 16 sept – 22 october. Ben Brown Fine Art Gallery

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle