Rafael Pérez Evans is best known for creating temporary sculptures from basic food stuffs, interrogating our relationship to food and exploring the complex relationship between the urban and the rural.

Last summer, Pérez Evans dumped 29 tonnes of carrots in the courtyard of Goldsmiths art school for his installation Grounding and for his current exhibition Handful at the Henry Moore Institute, he has flooded one of the museum’s rooms with milk and installed two giant grain silos at its entrance.

Here, Millie Walton speaks to the artist about working with perishable materials, fetishisation and visual disturbances

How do you think your upbringing in a farming community in Spain has informed your artistic practice?

My mother was Welsh. She came to Spain, and became a translator, and I was born in 1983. Then, my father and Spanish side of the family are part of a farming community that has been directly affected by accelerated modernisation. My dad had lemons and then avocados, and that way of living was no longer sustainable due to market devaluation of products. Seeing him have to negotiate that was an integral aspect of my childhood, and the wider changes in southern Spain have been a pivotal aspect of my understanding of how progress erases ways of being that are less profitable.

On a more personal level, I always wanted to run from the farming culture as a teenager because I thought that way of living belonged to the past, to the Franco era and a backwards mode of existing in the world. I wanted the glossy, Wolfgang Tillmans, urban, slick lifestyle. It has taken many years to do a full circle and return to less “shiny” things.

What inspired that change of perspective?

I guess it was a disappointment with the gloss of the city. As a queer person I had this idea that I had to migrate to the city to become free. I thought the city was the solution to all the shame I had from being the son of a person (my Dad) who left school at fourteen, and also the shame of being part of the “backwardness” of the farming community. But the city wasn’t the solution to my freedom, and now I’m questioning: what does freedom look like today? I left the UK in 2010 due to a lot of disappointment in my life, and I returned two or three years ago to work even though I said I never would. My whole experience of the city and the countryside is conflicting and my work explores that relationship.

What drew you to start incorporating food stuffs into your work? And what are some of the challenges of working with perishable materials?

I was making video and photographic works and around 2010, I started to feel a disconnect between my body and mind. I was only thinking through my eyes and I had cut out my hands. I felt very lost in my life in London at the time and I needed to reconnect to something beyond the concrete of the city. So, I started working more with my hands. I went to markets and saw the various foods that were lying around. They have a blunt kind of immediacy to them, which appealed to me on an instinctual level. I got attached to things that had a certain patina of dirt, things that could possibly counter the shiny gloss of the city.

I often lean into sites of hopelessness. I started thinking about things that are more difficult to articulate, and how people find ways of expressing those things. I think perishable objects act as a kind of immediate memento mori, they remind us that we’re also going to disappear.

In terms of the challenges of working with these materials, my sculptures are time-based, they have a certain time frame in which they exist. This creates questions around physical space: how do museums and galleries present these works? How long do we let the fruit or vegetables exist? There’s also the issue of archiving and collecting. To negotiate this, I make a contract with specific instructions in a similar way to Felix Gonzales Torres’ sweets. Then, there’s also the issue of food waste. I’ve been thinking a lot about how, as an artist, I might be contributing to, or can avoid contributing to this issue.

In displaying food, in its raw form, as artworks in a gallery “white wall” setting is there a risk of fetishisation?

I understand fetishisation as a way of control so if I fetishise something I have a certain power over it. I guess we have power over food in that we, as consumers, usually have very little awareness of the chains of productions. With my piece Grounding that power structure, in my opinion, was temporarily removed because the piece was so large that it offered a different viewpoint of the material, which in that case was carrots.

Back in the day, I spent a lot of time looking at land works by artists such as [Robert] Smithson who trusted the possibility of working at a very large scale, but also people like Gabriel Orozco who went from the monumental carcass of a whale to a shoebox at the biennale years ago. I think, for me, it’s about trusting that different scales can have different powers and it’s also about engaging different bodily sensations.

Consumption and farming is inextricably tied up with conversations around the environment and climate change. How do you see your work contributing to these dialogues?

In a material sense, some of my works around agricultural protest attempt to observe more voices in the struggle of central policies that devaluate workers, and their livelihoods. I am trying to see the complexity of the crises from the perspective of the people who are getting their hands and feet dirty producing and collecting our food in the fields. In my opinion, it is important to bring those voices into the rewriting of new ecologies, which are often written by an academic, urban class leaving very little space for other communities to contribute to the conversation.

Tell us about your current exhibition.

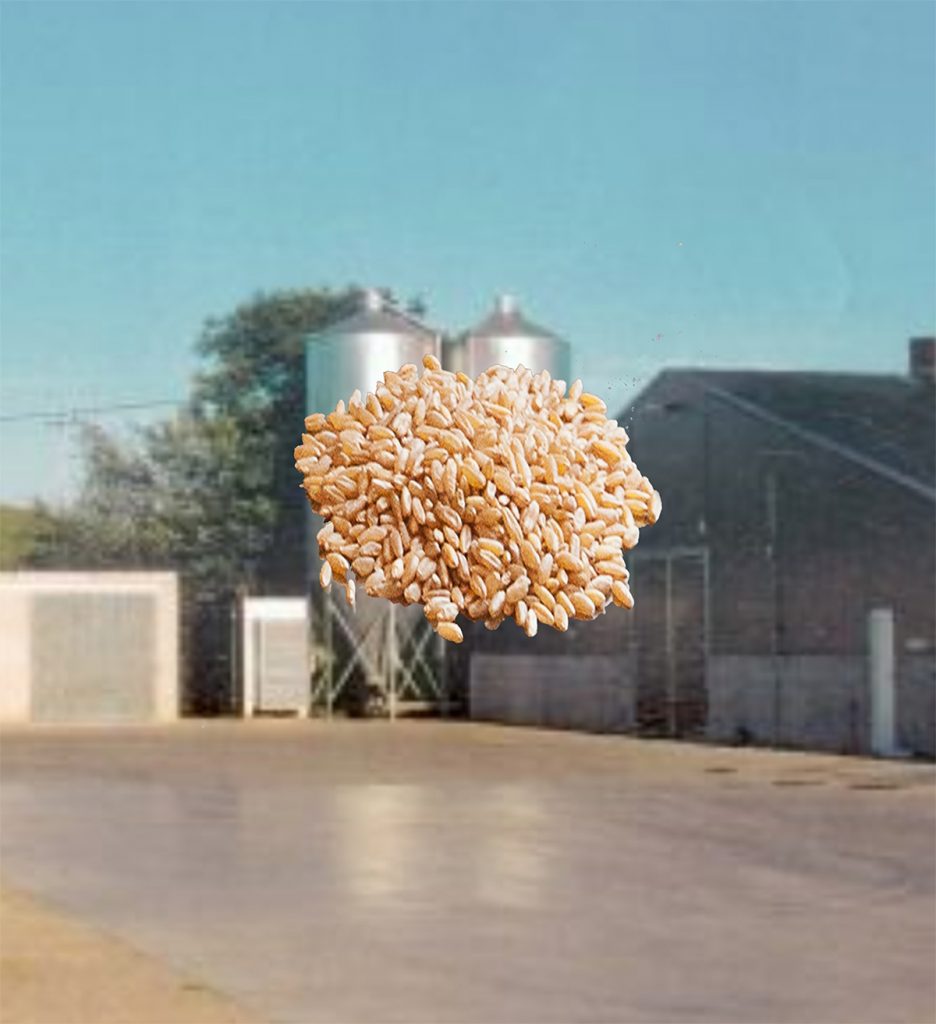

I worked closely with Laurence Sillars, the curator and director of the Henry Moore Institute, to build up the show and the works came about after thinking about monumental scales of European food protectionism (monstrous mountains of grain, for example) and how this is tied to the devaluation of produce. In response to the devaluation, many farmers dump their devalued products in areas of the city as an act of protest. I’m interested in how people that don’t have a voice, or whose voice has been erased, find a way to speak; in this case, it is by creating visual disturbances in the city, which I find very powerful. So with all of this in mind, I created a work entitled Mountain which is two, very large grain metal silos which stand outside the museum. They are empty and to me, they look like metal carcasses. Their scale touches upon a sense of alienness, of a lack of control, which relates to the unsustainable collecting of tones and tones of food.

In opposition to that, I have one handful of grain inside the museum, which is what’s needed for our immediate bodily survival. I also have a piece called Lake which is a room flooded with a milk solution, which follows the gesture of farming protesters that voice their helplessness through material. The work also looks at how visual languages are born from this very difficult place of devaluation, which is a devaluation that devalues the very bodies that produce our foods and in turn, uproots their relationship to the lands that make these foods.

The title of the show Handful, alludes to the hand, but also to the idea of being a handful or a nuisance. For me, a certain amount of trouble or disruption is important. I like seeing the smile on the protestors’ faces after they have done their gestures.

Over the past year or so (partly due to the pandemic) there seems to have been an increasing focus on nature. Many people are choosing to move out of cities and there are projects to develop rural spaces within the urban environment. Is this a step in the right direction?

I think any movement towards creating proximity between the city and rural is a plus. However, for me, the interesting idea here is how can we move beyond an edenic perspective of the rural? How do we stop fetishising the outskirts of the city as places of pleasure and become connected to something more layered and dirty which is making foods, chains of production and consumption.

I would say we need a complete re-development of what a future city could look like and that’s were the idea of an Agropolitan city comes in. As Spanish writer and essayist Jaime Izquierdo explains, “The city is the place where man cultivated abstract thought, where religion and politics were born. From its foundation until the Industrial Revolution, maintained a symbiotic relationship with the countryside through a round trip that linked the lands of the peasants with the food market. Today, that relationship is broken and it is necessary to rebuild it. The Agropolitan city is the one that recovers, rehabilitates and updates the city’s relationship with the countryside through new objectives and innovative management instruments.”

Many of your works echo the language of agricultural demonstrations. Do you view your work as a form of protest?

I think protesters have a lot more at stake than my art does, so I wouldn’t be able to place myself in that same place and it would be silly of me to do so. I think art has a lot of power to change things but also it has many limitations – the important thing for me is to try and enter the dialogue between those two positions

Are there any artists who have been particularly influential on your work?

I have a kind of imaginary compass of artists that help me navigate where to go when I’m making work. Robert Smithson is someone I go back to very often. I also look a lot at the 90s art scene in Mexico, people like Orozco, Melanie Smith and Francis Alÿs amongst other artists who were thinking about ways of creating a new ecosystem of art. David Hammonds is also a master at re-orientating our gaze to important places through simple materials and gestures. Also people like Derek Jarman and Pepe Espaliu whose anger guided them until their deaths during the earlier days of the AIDS crisis.

I also read a lot of biographies of artists, the lives of Leonora Carrington and Jean Genet, for example, were so incredible. It’s often difficult for me to find a way to navigate the world now that most of us live in pixelated rooms inside our phones and so, more and more, I find myself looking at books and stories for inspiration.

What’s next for you?

I’m currently developing a new installation work with Jesus Alcaide, a great Spanish curator. We are looking at where queer communities and southern, working class, land workers meet within the barbaric and by barbaric, I mean stereotypes of being backwards or non-human, closer to animals. In other words, I’m looking at how these two worlds and communities are connected in a place of being shamed. I’m in the process of creating some large-scale pieces as well as a new sound work, which is very new for me as I never work with sound. I am also developing a new large installation that will involve the whole production process from seed to distribution of a certain food.

“Rafael Pérez Evans: Handful” at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds runs until 29th August 2021. For more information, visit: henry-moore.org/visit/henry-moore-institute

Featured Image: Detail of Lake, Rafael Pérez Evans.

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.