Annegret Soltau’s practice is an exploration of identity and more specifically, the female body. Since the 1970s, she has challenged conventional notions of representation through performance, photography and collage.

Here, Soltau discusses finding artistic freedom through her own body, and why her earlier work was marginalised and ridiculed for its depiction of pregnancy and childbirth.

You’ve said before that you use yourself as a model in your art because you can go ‘farthest with me’. Can you explain what you mean by that?

If I use myself as a model, I don’t have to be considerate, I can do anything with myself: “use” my portrait or my body as material. It doesn’t mean that I just want to portray myself, but that I see myself as a person, as a woman especially.

Looking back on your career, how do you think your work has changed in terms of output and approach?

The 1970s was a decisive period. Women emancipated themselves from old ideas and role models. As was said at the time: “the private is political!” That really impacted me, too. After studying painting and graphics at the art academy in Hamburg, I broke away from traditional techniques. I eventually found performance and worked with my own body. For me, the body became a kind of “battlefield,” and I gained a new freedom through it. Through this commitment to using my body, I was also able to include various life processes in my pictures, like pregnancy and ageing.

As many of your works deal with constraint and brutality in relation to the body, there’s an aspect of horror to the imagery. Is this a genre that interests you?

I wasn’t thinking about horror or brutality at first. It was more about making the picture physically, feeling it on the skin. I started using thread as a material. The thread developed into a kind of drawing, like a line on a sheet of paper or etching, in which the line is engraved on a metal plate. The thread became a haptic line, a trace on the skin. For me, it was really about touch. The threads that create the drawing are very visible yet they can be perceived as restricting.

Do you think it’s important for your audience to situate and understand your work biographically? And if so, would it be true to say that your practice is one of exposure and vulnerability?

Yes, I want to show vulnerability. My own personal background has shown me that as a person you are just thrown into life without being able to determine where you come from or know where life is going. But then comes the determination, it shows you what is possible, and that is biographically driven. You have to accept that and can work with it as an opportunity.

Can you tell me about the works you have included in the upcoming show Mother! at Louisiana Modern Museum of Art? How do you see them interacting with the other works and the wider theme of the show?

For years I have worked with my own life processes and with my own physicality. It was the same with pregnancies. I gave birth to a daughter in 1978 and a son in 1980. At that time, it was not a matter of course for female artists to deal artistically with pregnancy and childbirth. On the contrary, it was frowned upon and didn’t help one’s career. There was even a quarrel among women artists, with one side taking the view that you couldn’t be a good artist with children. That left a feeling of uncertainty, and I became afraid of losing my dream of becoming an artist.

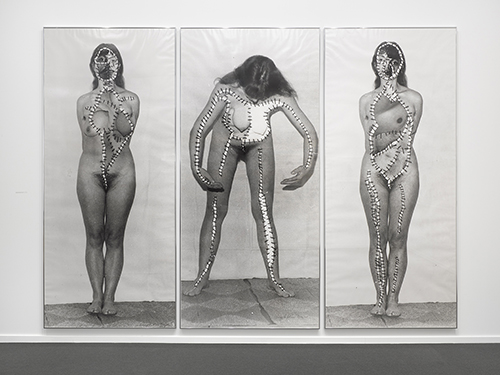

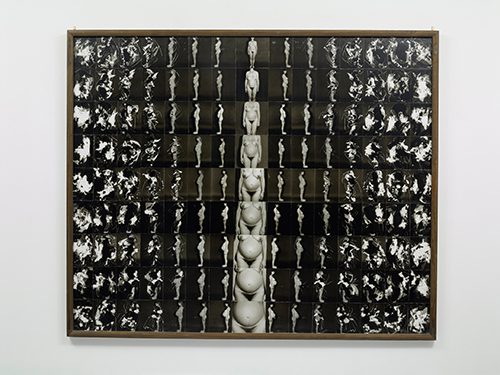

It is against this ambiguous background that my work on the subject of pregnancy and childbirth must be seen. I have incorporated these fears and doubts into my artistic work. Works from this series are included in the Mother! exhibition at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art exhibition. In the three pictures on display, I present myself as a pregnant artist. The works can be considered an affront to the traditional role of the mother with its marketable clichés.

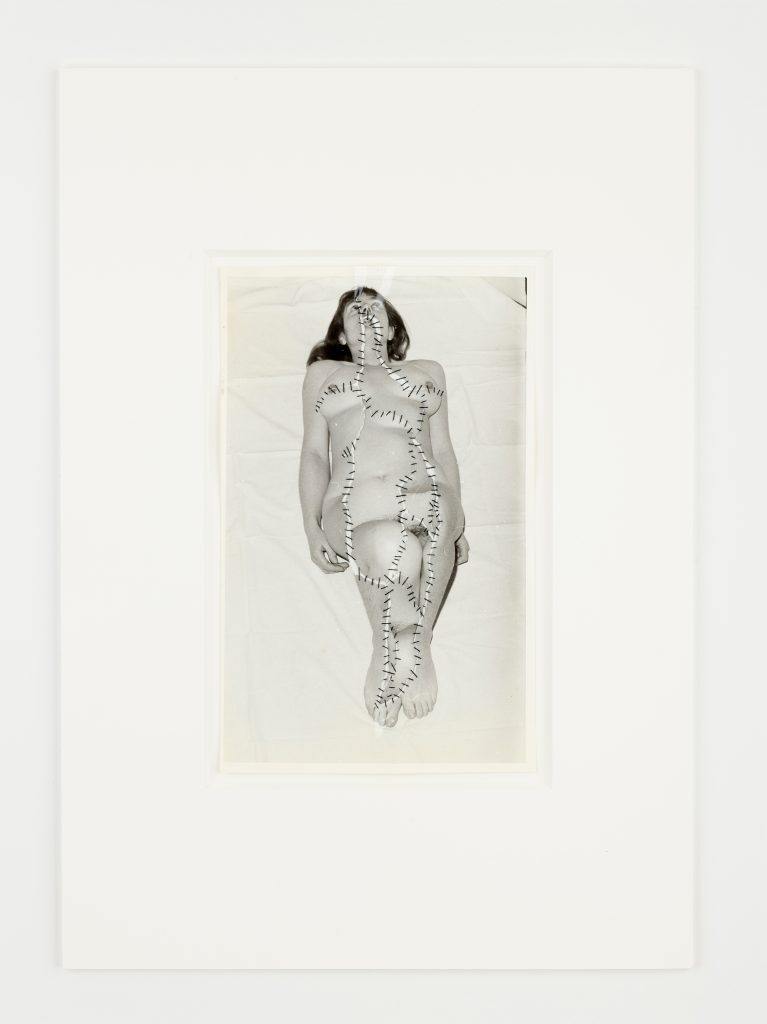

In the first picture I am lying on a white sheet on the floor. I am two months pregnant. The pregnancy is not yet visible on the outside, but my inner state is torn. So I ripped out body parts and sewed them back together again with a black thread.

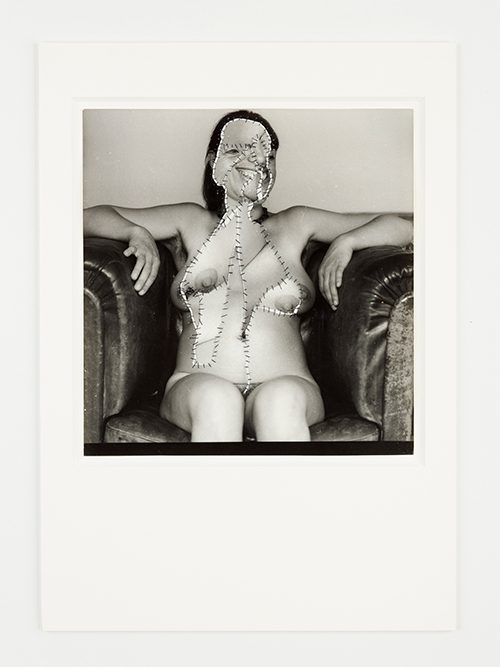

In the second representation, I am sitting as a pregnant woman in an old leather armchair, the expression is challenging and grotesque with an exaggerated laugh, the breasts displaced and the pregnant belly as if slashed and sewn up.

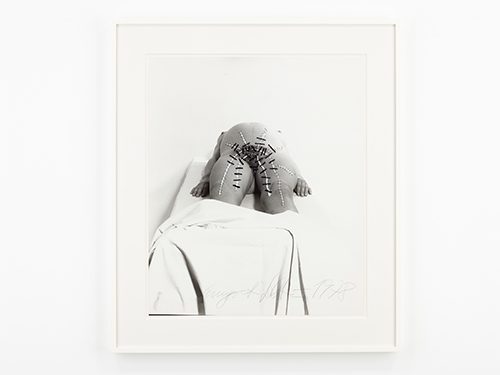

In the third picture On the birthing table, I am lying heavily pregnant on a table with a furrowed and sewn vagina. This representation indicates the fears of being at the mercy of death; every birth is also an experience of death, symbolic of one’s own death as an artist.

How did your own experiences of having children affect your practice?

My situation wasn’t particularly stable: an artist’s existence with little financial means. But I wanted children very much. I imagined my two children had always been inside of me. I couldn’t explain the desire to have children in any other way. Colleagues did warn me, however: “Don’t have children, it will destroy your artistic creativity!” But I didn’t listen, I just wanted to experience it myself, even if I should fail.

This dichotomy is what drove me and maybe my own origins as well. I was a child myself who wasn’t meant to be born. It was shortly before the end of World War II when my mother became pregnant with me. She was without training and completely penniless and lived and worked for a farmer as an agricultural assistant in a small village in northern Germany. She had a casual acquaintance with a soldier who never showed up. She didn’t want the child, so she tried to find a doctor to have an abortion. Unfortunately (or fortunately for me), no doctor was found who could help her. I was raised by my grandmother, and we initially lived in a horse stable because her house had been hit by a bomb splinter, burnt to the ground, and there was no other place to stay. As a child I felt very lonely and abandoned. In the village I was called a changeling, and the peasant children were not allowed to play with me. You can read more about my story in my autobiography.

Why do you think the art world has been so squeamish about the idea of artists being mothers, and also about honest portrayals of motherhood?

While it was difficult to be both a mother and an artist, it challenged me and brought this complex notion to my work. I worked at nine months’ pregnant. It was sometimes like a race, where I was working simultaneously against my changing body, and I couldn’t put it off until later, even if I didn’t have the time or strength.

There were also hardly any examples of this type of work at the time. This subject was not of interest to the art world then and was rejected by galleries and museums. But that didn’t bother me, there was nothing else I could do. It was predetermined for me. The attacks and judgments from other artists or the art world ricocheted off me. While it was often hurtful, there was no other way. I wanted children and wanted to be an artist, too.

This conflict resulted in an abundance of video and photographic works, all centred on the subject of pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood. My work then was marginalised and ridiculed – even by feminists, which was particularly painful.

I find great satisfaction that this topic has now found acceptance in the art world and is no longer ridiculed or viewed as retrograde. To combine life and art, body and mind was like a revelation for me.

There has been an incredible change in the perception of motherhood that was not found in my generation. Young artists no longer want to bow to the dictates of standing for or against motherhood.

What are you currently working on?

I am currently working on my “personal identity” series. It is a job that started with my birth certificate and is supposed to end with my death certificate. I insert personal documents in my passport photo portrait in which my data is digitally stored, as well as MasterCard, Passport or other documents from my everyday life.

Annegret Soltau’s work will be included in “Mother!” at Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, opening on 6 April 2021. For more information visit: louisiana.dk/en

Featured image: Annegret Soltau, Körper-Eingriffe (schwanger) [Body intervention (pregnant)], 1977/78. Set of 3 gelatin silver prints.

All images courtesy the artist and Richard Saltoun Gallery

Millie Walton is a London-based art writer and editor. She has contributed a broad range of arts and culture features and interviews to numerous international publications, and collaborated with artists and galleries globally. She also writes fiction and poetry.