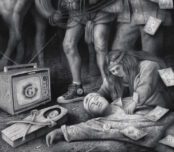

Rankin, the renowned British photographer, film-maker and publisher, has continually pushed the boundaries of visual culture, merging innovative techniques with social commentary, in his photographic work and with magazines like Dazed&Confused, AnOther, and Hunger. His recent exhibition, “FAIK,” held at Annoy Gallery in Kilburn, exemplifies this commitment, exploring the intersection of artificial intelligence and artistic expression. In “FAIK,” Rankin delved into the complexities of AI technologies, investigating how they influence creativity and challenge traditional notions of authorship and authenticity.

The exhibition showcased a range of works that highlight Rankin’s experimentation with AI, generating captivating imagery that questions the role of technology in contemporary art.

Rankin has been confronting the paradox of AI as both a tool for creative expansion and a potential threat to human creativity, inviting viewers to engage in a dialogue about the implications of this rapidly evolving technology.

“FAIK” not only reflects Rankin’s innovative spirit but also serves as a critical commentary on the cultural anxieties surrounding AI. By utilising AI to generate new forms of art, Rankin challenges audiences to reconsider their perceptions of creativity, pushing them to reflect on the future of artistic practice in a world increasingly shaped by technology. The exhibition, merging artistic vision with technological exploration, positions him at the forefront of contemporary discussions on the evolving landscape of creativity in the digital age.

Trebuchet’s Barry Taylor (author and philosophy educator) met with Rankin for a wide-ranging conversation about his experimentations with AI and his views on the challenges and opportunities presented by these technologies for artists and society in general.

Rankin: I feel we’re at a point where, for me anyway, we are on the precipice of something massive. It feels almost like a void—a deep, wide space without a bottom. We are literally at the edge of this thing, and it’s so big that I think no one is ready for it. I’m quite robust in discussing this, yet I find it hard. I did an interview with the actor Jason Isaacs about it, and it felt like end-of-the-world stuff—event horizon stuff. I love the work I’m creating, but I hate that this technology is here. It feels like we’re lemmings, and so few people are even looking. They are going up a hill without realising there’s a massive drop ahead, and we have no idea where it goes. Maybe it does have a bottom, maybe it leads to somewhere else, and optimistically, it could be amazing. But we just don’t know.

If you don’t think about it, you can ignore it. But I think about it every day—I’m writing about it and making work with it. There are extraordinary things that come from this process, but it has this shadow of not being real. It feels ephemeral, like working with ghosts. Yet, I made two magazines about it and an exhibition. Those were real, and I am bringing a reality to it. I find it completely overwhelming daily, but there’s a friction where I love using it and hate it simultaneously. I am always amazed by what it can do. I’ve been generating songs on Suno, and they are pretty good, considering it’s a machine creating them.

The idea that AI isn’t creative is ridiculous to me. I know it is creative because I’m using it creatively, so the potential of what can be made is endless. But at the same time, I wonder what we are making it for. If there is going to be no future, if we are all going to be gone in 20 years, what am I making this for? I end up making things for the sake of making them, trying to understand it in the moment. Yet, I can’t let go of the idea that the future will be okay. I keep thinking that surely the future will be fine because we will figure it out.

But when you have someone like Geoffrey Hinton, the godfather of this stuff, saying there’s a 10 to 20% chance of human extinction, it’s alarming.

That’s interesting because technological innovation has always been accompanied by fears. For instance, when cars and trains first appeared, there were concerns about their impacts. People feared that if you went over 15 miles an hour or something, your soul would bounce out of your body. There was always an aspect of technology that we embraced without fully understanding its potential consequences.

What I find interesting is that with AI, there’s this dual component of creative possibility combined with growing cultural concern about the extinction of humanity. We’ve shifted from apocalypticism to extinction. It’s no longer an apocalypse rebellion; it’s Extinction Rebellion. There’s a sense we might be wiped out, and the fears associated with AI tap into that anxiety because it is an invisible technology that invades the core of our impulse to create. We should think about AI beyond just the technological element.

Yes, absolutely. Currently, the everyday user of ChatGPT or Claude.ai is using it practically for ease, like rewriting emails or drafting presentations. However, anyone who studies it for more than five seconds knows we will soon be using AI agents. They will shift the fabric of society. I meant we are on the precipice of something enormous. Predicting it is almost impossible because the way we interact with each other will completely change. Social media might not even be the main form of interaction in five years.

That’s true. But currently, what’s being prioritised is the utilitarian nature of AI. While this is great on one level, it raises questions about what happens to society when automation displaces people.

Exactly. That’s one conversation. Another is how this technology becomes a part of the fabric of life. Especially when the social contract of society is already fragmented by social media, there’s been no responsibility taken for the people perpetuating these issues.

There seems to be an arrogance in how some leaders, especially in tech, address these issues, as if it’s an inevitability.

Right. It feels like there’s a race to the bottom in some AI companies. They speak as if it will be good for humanity, but it’s hard to see that when we’re living in such vulnerability. The fabric of what we’ve developed over 2000 years has been broken apart by some individuals who took ideas without giving them proper thought.

Yes. There’s a perfect storm of vulnerability and greed.

Exactly. I keep looking at this and wondering why they seem to want to build a war chest of money to live in some godlike Elysium while the rest of society is left behind. You can see the cards they are playing.

Yes, and when people try to rationalise it by comparing it to past technological innovations like the transition from analogue to digital, it’s not the same.

I agree. This isn’t like that at all. There’s a utopian narrative that proclaims a bright future for humanity, but it is also coupled with a calculated capitalist drive.

This drive seems to dismiss our physicality, where people fantasise about uploading their consciousness as if AI represents the pinnacle of what it means to be human. There’s an argument that what makes human art vital is that it comes from our limitations. Art emerges from what we don’t know how to do, while AI has limitless possibilities. Your exhibition seemed to reflect this dynamic—wrestling between human limitations and the potential of a new technology.

It’s extraordinary. I can hardly believe that with very basic prompts, especially using my work as source material, I can create so much. I’m trying to figure out my next project around AI. I’m writing about how I feel and using it to create work that pushes the limits of what I can do.

Currently, I’m working on a project titled “The Absurdity.” I’m generating my work as various styles and genres. For example, I made some Japanese pottery based on my photographs over the weekend. I’m attempting to tell stories through my work and re- examine them through the lens of me and the machine creating new forms.

I’m always remixing my work with the machine while exploring art history, from Bernini sculptures to Japanese manga art. This process allows me to reframe my work as a more artistic endeavour than just photography. My work is diverse, so I’m using apps that mythologise images and creating bronze sculptures from them.

I made sculptures of dandelions on fire and displayed them in a traditional form at the British Museum. It’s nuts because it helps me understand why I made those works in the first place. It’s not soulless; my original thought is there. It allows for play, and I could make all these things in reality based on what I’m doing.

I used to spend around £30,000 to create a bronze piece through photogrammetry and now I can generate it in about 30 seconds with AI. When I look at work through these new methods of making, it starts to make more sense. It’s not just about photographic realism; it’s surrealism.

Your engagement with this technology is starting with your own work and your recent exhibition reflects your own artistic journey while exploring how AI changes the creative landscape.

Yes, and that’s the difference. Many people can use these technologies without their own artistic context. In the exhibition “FAIK,” I posed philosophical questions about the technology’s output, like why all the gods are male.

What drew you to these questions?

It was fear—the fear of being replaced. It’s not just imposter syndrome; it’s replacement syndrome. I watched people use AI interestingly, like photographer Phil Toledano, who created images of Trump in a McDonald’s setting. He was using AI to create art that was questioning and innovative. I thought I needed to test this technology and see what it could do.The first thing I did was try to create photographs of famous people who had died, and it was very successful. I was struck by how critical people were of the final results, and I thought we should focus on the success rather than the failures. The process felt similar to dealing with death—anger, sadness, reflection. Initially, I felt dirty, like I was letting my medium down. But I realised I was becoming an author of something encompassing. I even wrote, “Imagine if I hadn’t told anyone this was AI.” People seem to have a specific perspective on AI-generated work, and if they don’t know, they aren’t burdened by that.

There are some universities are now discussing this idea. There will come a point where we won’t even ask if something is AI-generated or not, and I think we are closer to that than we realise.

That’s true, especially with the rapid advancements in technology. What’s interesting is the negativity around AI and what you called replacement syndrome. There is genuine concern and fear, especially in certain sectors of society.

Right. There’s a positive and a negative side, but I think the anxiety around technology stems from a lack of understanding. There’s always an initial wave of dismissal rooted in unconscious anxiety about change. And that anxiety is present now. If you have nothing but leisure and don’t have a job, your purpose shifts dramatically. Society isn’t ready for that shift.

Without a framework to support people through this, we risk creating more discontent.

Yes, and I don’t think the current form of capitalism has any desire to create that framework. There’s a Disneyland dream of a society where everyone works four hours a week while robots take care of everything.

Yes, the utopian possibility of technology always seems built on a false premise.

Yes, I think coming to terms with the absurdity of life is crucial. It’s about wrestling with complications. We’ve been conditioned to seek simplistic solutions, and that’s where people can be taken advantage of. I want to engage with that complexity. I’ve been thinking more about the self and how we need to question it. That’s the central question for me: how do we see our subjectivity in a world with AI?

–

FAIK & FAIK OFF by Rankin

May – June 2025

Annroy Gallery

110-114 Grafton Road

London

NW5 4BA

Main image from FAIK by Rankin

Barry Taylor writes and speaks about the intersections of philosophy, theology and contemporary culture. In past, he was the road manager for AC/DC during the Bon Scott era before becoming a Los Angeles theologian.