[dropcap style=”font-size:100px;color:#992211;”]A[/dropcap]t the turn of the century (19th 20th) intellectuals artists and scientists were beginning to become interested in the subtitles of the mind and the self in general. This represented what is sometimes called ‘modernist optimism’ (mass production, scientific progress, and emancipatory politics) the forming of the Modernist mind set (see here for more information)

This culminated in, among other things; psychoanalysis and modern psychiatry, in the arts the Surrealist movement probed the unconscious and similarly in literature existential themes abounded exploring freedom and autonomy.

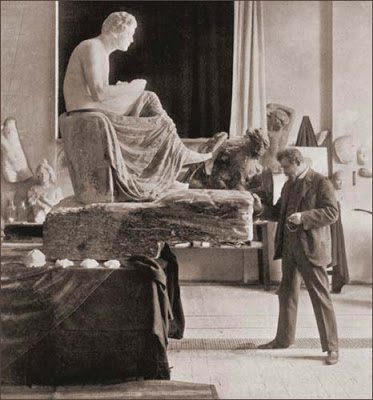

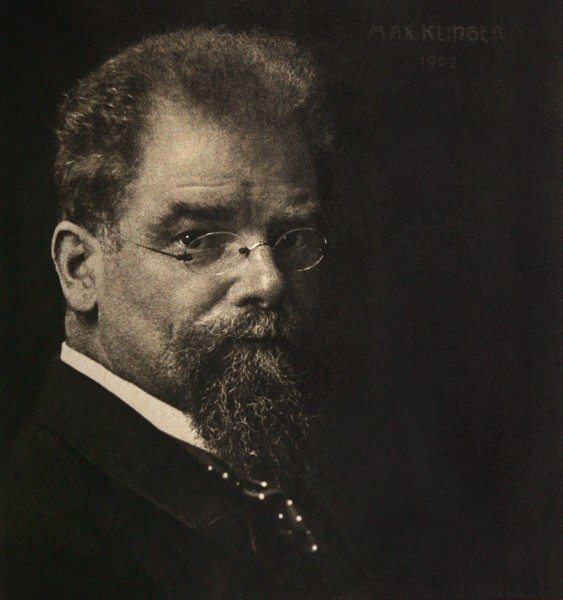

Max Klinger 1902

These are weighty themes not least because they often broach subjects which we may not wish to think about (death, violence, subjection, agency or lack of it). It can also be difficult to simply dive into Nietzsche, Melville or Poe, popular reading at the time. Psychoanalysis too can be difficult to penetrate without references and any depth of understanding needs connections across fields and media.

With this in mind the celebration and exploration of an often overlooked proto-modern artist, at least overlooked in the UK, Max Klinger, (born February 18, 1857, Leipzig, Germany—died July 5, 1920, near Naumburg) is the subject of this article.

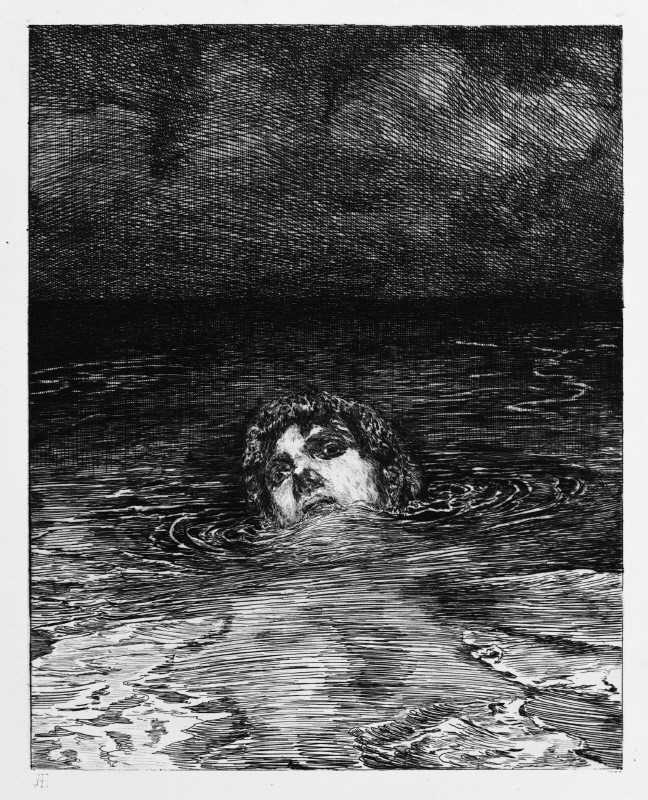

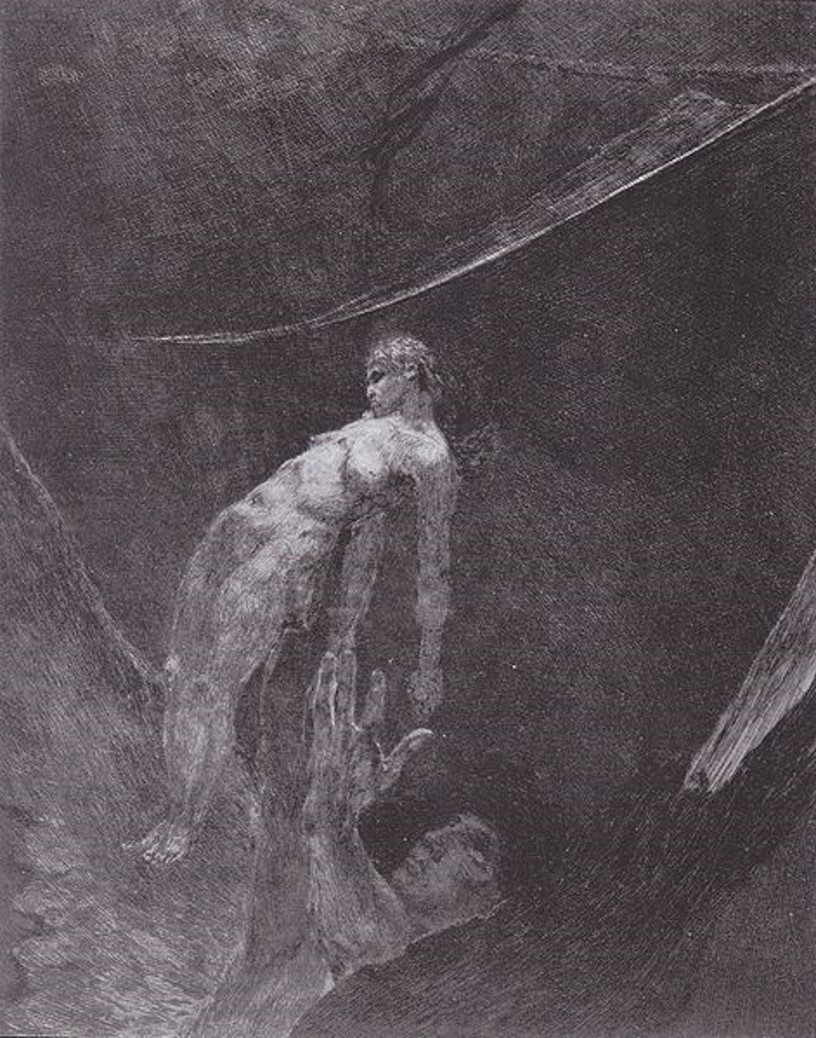

‘Drowning’ etching, 26.2 x 21.5cm, Max Klinger.

The above image is an etching by the German born symbolist painter Max Klinger who lived in Germany at the same time as Sigmund Freud (they were the same age, 1856-Freud, 1857-Klinger, and enjoyed successful careers in Germany/Austria simultaneously). Klinger had an interest in the work of the philosopher Nietzsche (as did Freud although he described Nietzsche as a distant/remote figure) and it is possible the work, ‘Drowning’ was inspired by Nietzsche’s writing on the ‘down going’, where people were encouraged to explore the dark recesses of their inner world and return to a shared reality, changed and stronger.

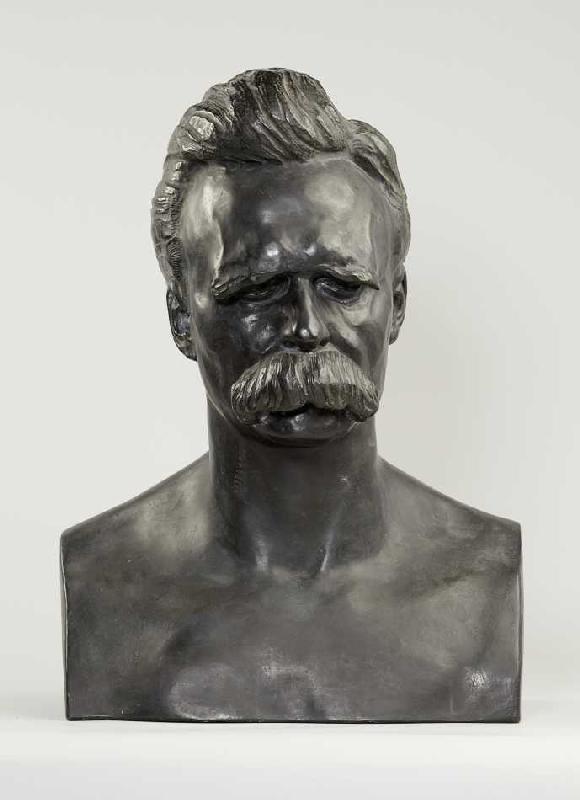

Friedrich Nietzsche (1904) Max Klinger

This was the teaching that Nietzsche put into the mouth of Zarathustra, the principle character of ‘Thus Spake Zarathustra’ – a Christ -like figure who preaches radical ideas throughout the text encouraging people to overcome themselves and transcend local/national particularities. A proto-Analyst perhaps?

“Following a lengthy struggle with mental illness, the German philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (b. 1844) died in 1900. In his honour, his sister established the Nietzsche-Archiv in Weimar and turned to Max Klinger, a leading sculptor, to execute a bust. Working from a death mask and photographs, Klinger produced several alternate versions, of which a monumental marble was chosen for the archive,” National Gallery of Canada

Klinger had a sustained interest in Nietzsche and shared the great philosophers love of brooding classical music. He was a part of the influential Secession movement displaying art in Vienna where Freud was publishing his first works.

Klinger and fetishism

Klinger produced a series of works Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove (published 1881) which explored the obsession of attaining the aforementioned object and acts as pre-fetishism (theory; Freud 1927) visual exploration of the strange associations that arise where by an object or ‘non genital body part’ becomes the focus of the subjects attention or desire,

“Sexual fetishism or erotic fetishism is a sexual fixation on a non-living object or non-genital body part,” American Psychiatric Association, ed. (2013). “Fetishistic Disorder

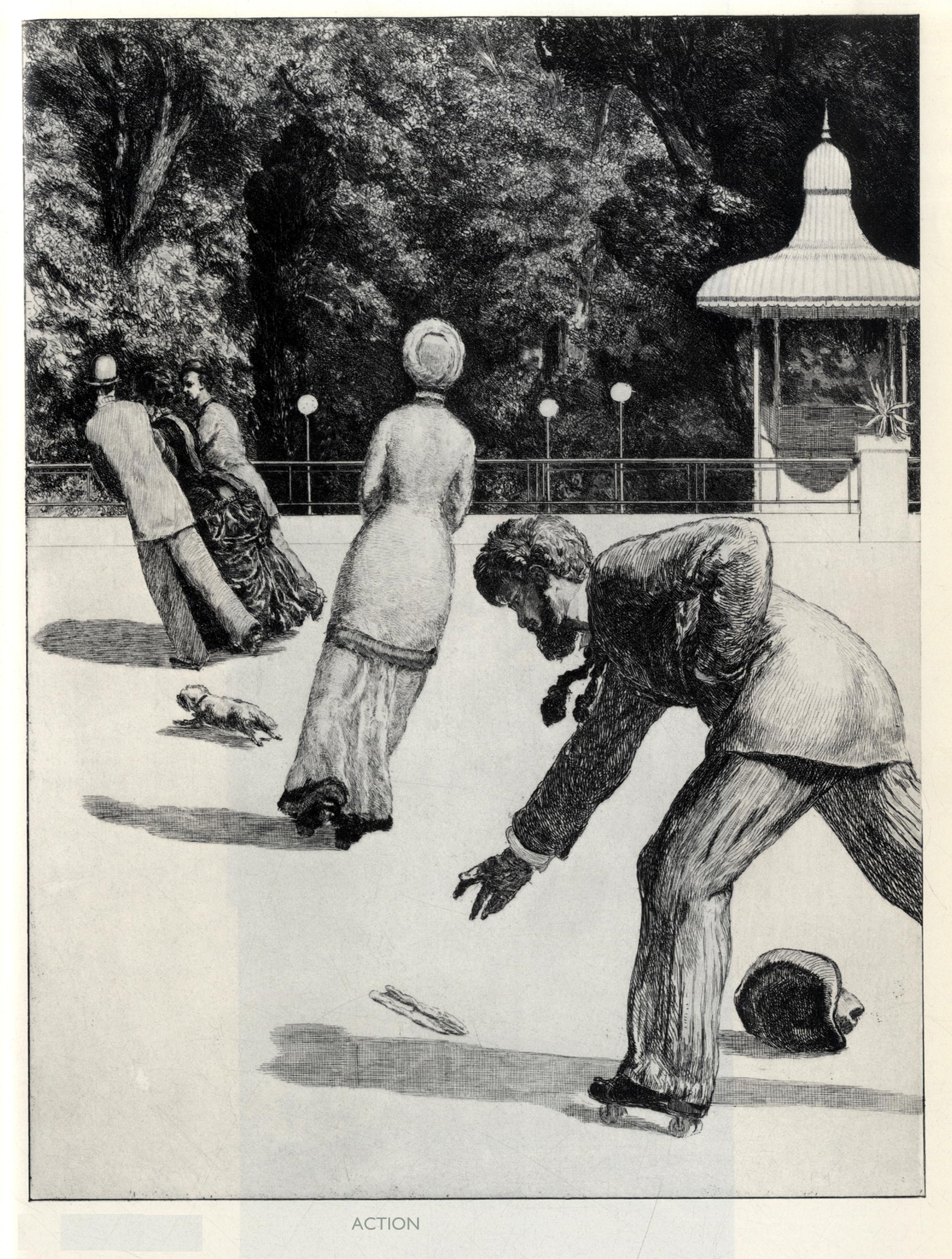

Image from Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove (published 1881). Printed in five editions

The two examples here (above and below) show hands desperately reaching for the garment. The glove, in this case a woman’s glove, covers the hand a tool of action and agency it acts as a kind of amplifier to the phallic power of the hand, in the same way that high heels (another fetishistic fashion item) amplifies the curve of the calf and thigh.

We might understand, if find a little coarse the function of high heels or say shoulder-pads in the obvious way they alter the stance or shape, whats interesting though is this effect is secondary and the fetish moves away from the exaggerated thigh or calf to the shoe its self which in its self comes to stand for something intrinsically sexual,

“In all the cases the meaning and purpose of the fetish turned out under analysis to be the same… the fetish is a penis-substitute… for a particular quite special penis that had been extremely important in early childhood but was afterwards lost… the woman’s (mother’s) phallus which the little boy [sic] once believed in and does not wish to forego” Sigmund Freud, ‘On Fetishism’1927

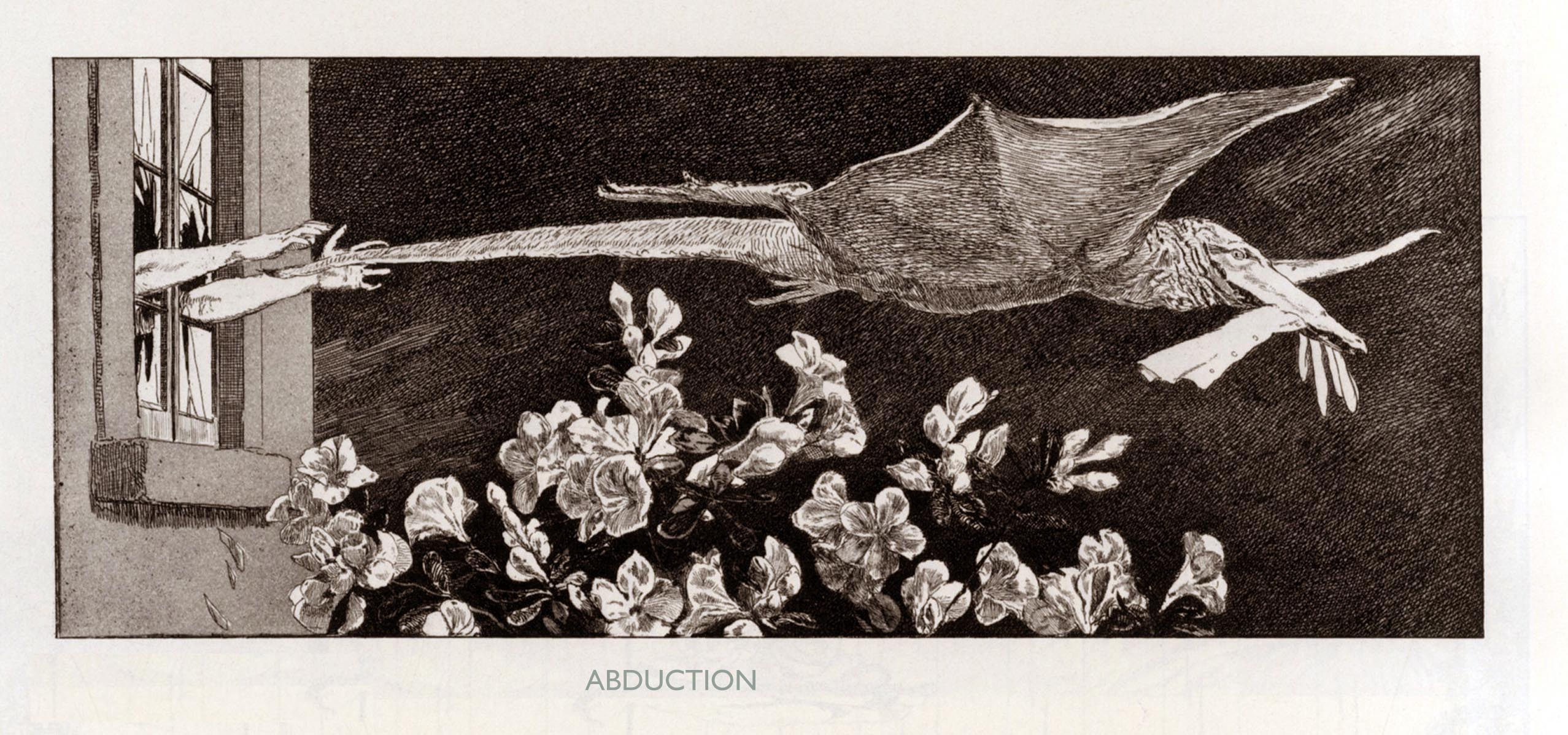

Image from Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove (published 1881). Printed in five editions

Klinger’s choice of the glove is more romantic in the classic sense but no less fetishistic, the token is a constant in the series and his masterful composition feels oddly modern. In first image shown here ‘Action’ Klinger displays his expertise in ambiguity and composition, we see a young man reaching down to retrieve the garment but he is positioned in such a way as to suggest he has cast a puck or stone (actually a little dog) across the ground toppling the people ahead who are falling like bowling pins rather than like bodies, giving the scene a dynamic feel which contrasts with the ordinary background and perfunctory task of picking something up from the ground. The fallen hat helps this illusion as it has the shape of a large bowling ball and overall the image is imbued with energy.

“After the success of A Glove, the print cycle soon became Klinger’s signature genre. Over the next several years, he explored the social issues that characterised life in modern Berlin. Generally regarded as the first German visual artist to address the social problem of prostitution, Klinger highlighted the hypocrisy of bourgeois morality and the injustices that often befell women in the city,”Salsbury, Britany. “The Graphic Art of Max Klinger.” 2016

Klinger’s symbolist foundation was significantly updated in his practice he was able to give the genre a characteristically modern and again proto-psychoanalytic feel.

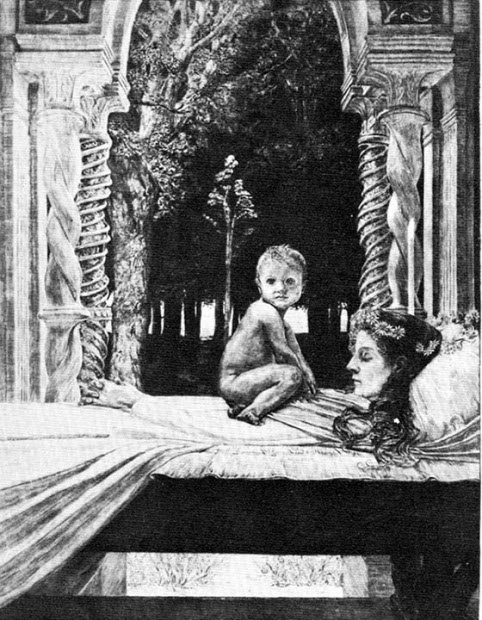

‘The Dead Mother,’ Max Klinger 1842

‘The Dead Mother,’ (1842) is just such an updating based on Fuseli’s ‘The Nightmare’ (below) it swaps religious superstition for psycho-drama and trauma. A dead mother is certainly a nightmare but the oddly positioned child is disconcerting giving the image a less obvious message, we cant say this is a melancholy piece concerned with the loss of a parent something much more ‘unheimlich’ [1] is in play the child is also a monster as well as a victim, perhaps even responsible for draining the life from the pallid corpse.

‘The Nightmare,’ Henry Fuseli 1781

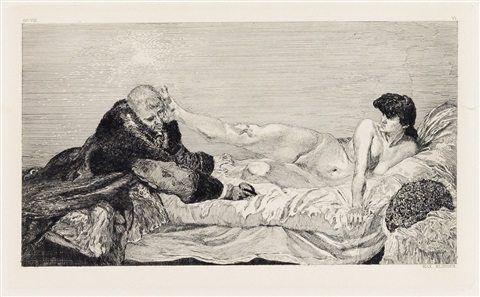

Klinger’s artistic skills, his contemporary and modern outlook and his activism (Klinger highlighted the hypocrisy of bourgeois morality and the injustices that often befell women in the city, ibid) ‘A Life’ shows a woman (a prostitute) receiving a proposition from a wealthy man wrapped in expensive furs, she in contrast is naked but her disdain expressed by her thrusting away of his head gives her a little dignity and makes him look grubby, perhaps his offer is too little or his persistence is boring her.

‘A Life’ Max Klinger (German, 1857–1920)

These qualities made Klinger an ideal influence on Surrealism and those who would be claimed by Breton as Surrealist. Led by Breton the Surrealists would also take Freud as their primary theoretical reference,

“SURREALISM: Pure psychic automatism, by which it is intended to express, verbally, in writing, or by other means, the real process of thought. Thought’s dictation, in the absence of all control exercised by the reason and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations,” André Breton, What is Surrealism? 1936

Breton had entered the first world war as a medical intern having been involved with Dadaism, he was absorbing and experimenting with psychoanalyitic ideas and had resolved to combine Dada with psychoanallysis to form his new movement which would seek as stated above to acess the unconcious (real process of thought).

Influence on Surrealism

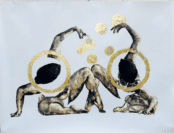

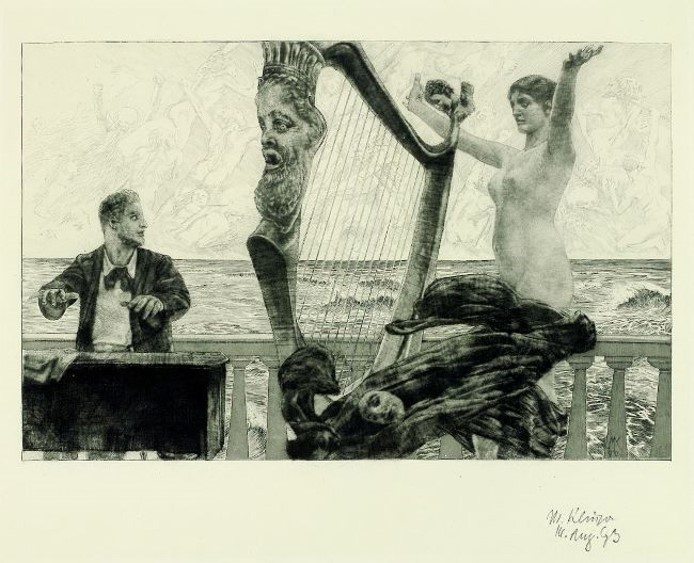

‘Invocation’ Max Klinger

“By the early twentieth century, Klinger’s combination of dark themes and the stylistic aspects inherent to print would be taken up by the Surrealists, who praised his exploration of the uncanny,” Salsbury, Britany. “The Graphic Art of Max Klinger.” 2016

Many of Klinger’s works contatined the combinations of incongruous elements and dislocations of scale that would become staples of Surrealism, perhaps most obviously influencing Max Ernst in his work ‘A Hundred Headless Women’ from 1929 where Ernst adopted the narrative style Klinger had used in ‘Paraphrase on the Finding of a Glove’ 1881.

Max Ernst, La femme 100 tête (or A Hundred Headless Women), 1929

“Max Ernst’s collage novel La Femme 100 têtes is seen here as a radical demonstration of Surrealistic technique, representing a dream world parodying and fetishizing the same cultural heritage as Klinger’s Glove Cycle,” Christiane Hertel, ‘Irony, Dream, and Kitsch: Max Klinger’s Paraphrase of the Finding of a Glove and German Modernism’ 2014.

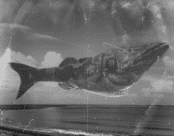

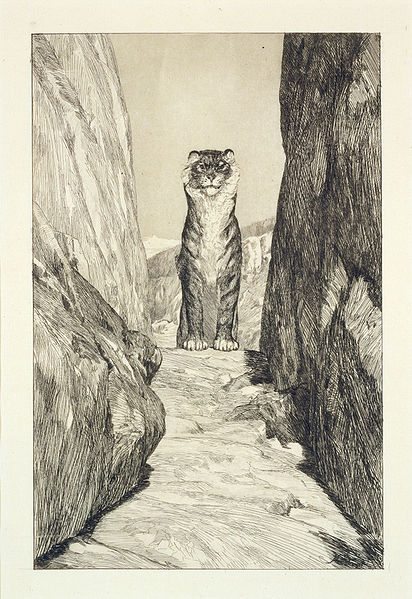

Dream like imagery was also hinted at in Klingers work as below (First Future) Pure anxiety, who hasent dreamt of a similar animal catching us out and awoken with a start! The Surrealists would emphsize sexuality and anxiety, freedom and the fear of death all subjects that Klinger had provided a wonderful foundation for.

First Future. Etching with aquatint, print 2 of the second edition.

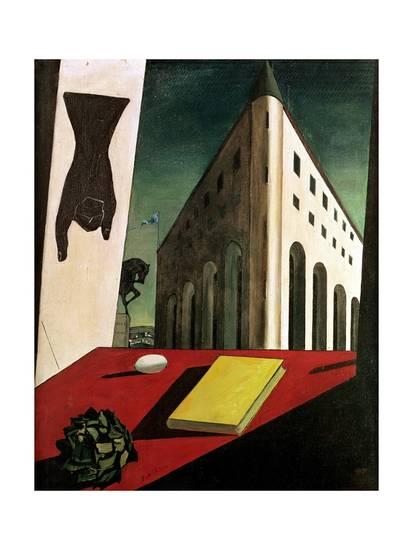

Klinger was also a notable influence on Giorgio de Chirico who brought a great deal of gravitas with his metaphysical works to the Surrealist movement. Klinger actually acting as his tutor at the acedemy in Munich.

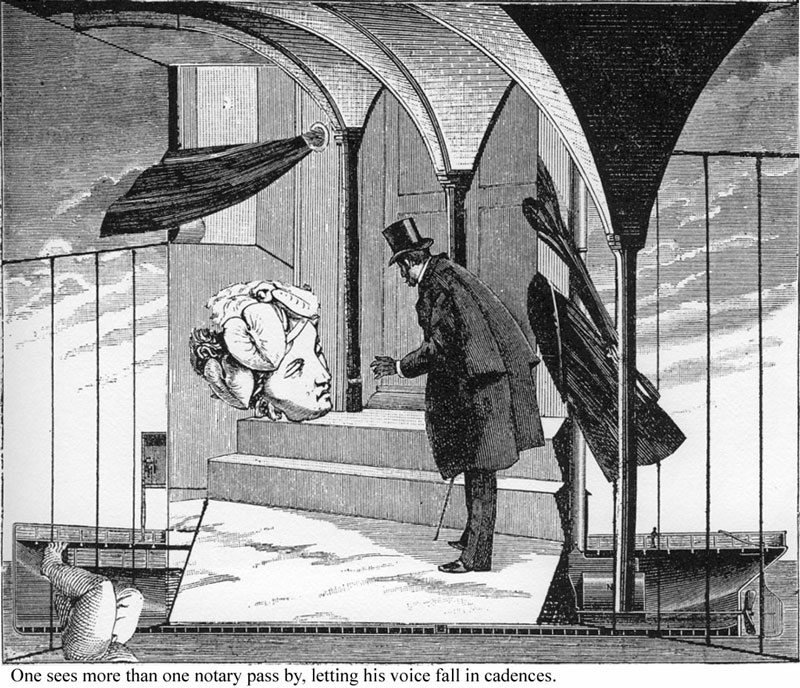

The Song of Love, 1914 Giorgio de Chirico

“he (de Chirico) moved to Germany in 1906, following his father’s death in 1905. He entered the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, where he studied under Max Klinger and read the writings of the philosophers Nietzsche,” “Propyläen Kunstgeschichte, Die Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts 1880–1940”, by Giulio Carlo Argan, 1990

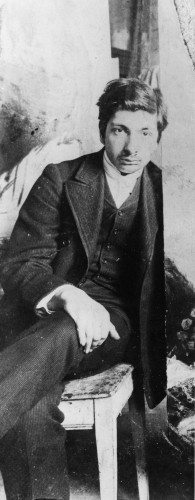

Giorgio de Chirico, Munich, 1907 where he was taught by Klinger

De Chirico was fond of tradition and poetry imbibing from Klinger his asthetic qualities (composition, striking incongruety, symbolist referrance) and mixed this with his own frank painting style,

“In autumn, 1919, de Chirico published an article in Valori plastici entitled “The Return of Craftsmanship”, in which he advocated a return to traditional methods and iconography,”Holzhey, Magdalena. Giorgio de Chirico. Cologne: Taschen, 2005,

This chimed well with Breton who was keen for a return to traditional skill after his stint with the anti-tradition Dada movement, their techniques (Dada) would be combined with metaphysical painting and underpinned and informed by the then new psychoanalytic theories of Freud.

Metaphysical gave way to oneiric (dreamlike) in Surrealism in the practices of Dali, Tangy and Magritte. De Chirico always retained his link to the term metaphysical and his interest in Nietzsche, De Chirico painted secenes of Turin many times the city that Nietzsche loved and eventually where he collapsed into madness.

Turin Spring, 1914 Giorgio de Chirico

The Freudian Unconscious

However, it is Freud’s work and his terminology which would come to dominate and define thinking around this inner world and its constant influence over ones life,

“The unconscious is the larger circle which includes within itself the smaller circle of the conscious; everything conscious has its preliminary step in the unconscious, whereas the unconscious may stop with this step and still claim full value as a psychic activity. Properly speaking, the unconscious is the real psychic; its inner nature is just as unknown to us as the reality of the external world, and it is just as imperfectly reported to us through the data of consciousness as is the external world through the indications of our sensory organs,” Freud, Dream Psychology: Psychoanalysis for Beginners

The image ‘Drowning’ certainly tempts the viewer into a psychoanalytic reading, is the subject/ego emerging from the unconscious flux or being consumed and dissolved into it? Is this not the risk when we deny the power of the unconscious? We risk the disintegration of our functional ego and yet the same is true when we engage it too eagerly this ocean of what’s impossible and repressed, should we stay too long in its corrosive waters.

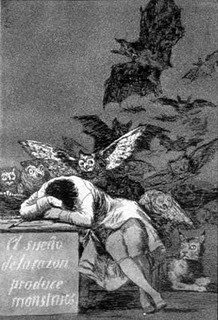

The image below from the work of Goya brings to mind Freudian logic that, dreams are for those who cant handle reality and reality is for those who cant handle their dreams!

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters’ Etching, Goya, 1797.

We see enlightenment man hunched and haunted by superstitions and monsters from his dreams, as if the grand project of the enlightenment was not the concurring of barbarian impulses and deep seated fears but rather a retreat from the field of this inner world, with Freud we have a wilful and sustained confrontation with this anxiety.

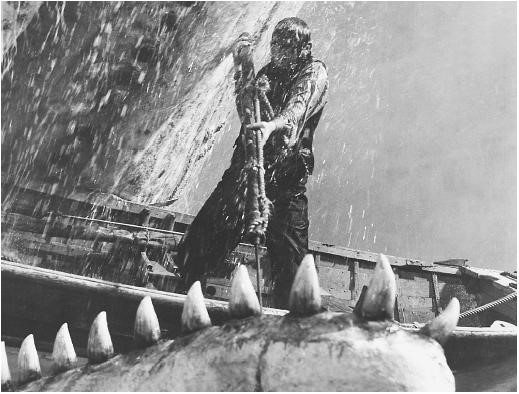

It is the fate of Melville’s Ahab from ‘Moby Dick’ to be destructive in his pursuit of the, ‘unknown but still reasoning thing’ like the sea that contains the great whale so too the unconscious is in flux, the space of primal drives and repressed thoughts and memories and like an ocean we might drown in it overwhelmed by this tension with our steady, functional whole self, the ego,

Ahab: ‘All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event-in the living act, the undoubted deed-there, some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask. If man will strike, strike through the mask!’ (Melville, Moby Dick, pg108)

Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (1851) was published five years before Freud was born and some scholars have pointed out that Melville is a kind of proto-Freudian figure, like Klinger he was fascinated by human psychology and Ahab is an interesting point in question.

Ahab recognises that there is a force beyond appearance’s the ‘pasteboard mask’ he identifies is ego in striking through this mask we arrive at the unconscious self. This great ocean is not mute, it has its own language and it sends messages, glimpsed in dreams hinted at in impulsive behaviour and symptoms. It is a ‘reasoning thing’ Turning from its voice we tempt the emergence of a monster/symptom, the unconscious message par excellence.

Still from film ‘Moby Dick’ directed by John Huston 1956.

Of course the great whale is this message for Ahab, it emerges like a repressed truth returning to wreck havoc on the ego. Ahab is the ego jaded and fragmented, by courting this truth to his destruction. In a sense does this not happen at significant moments of change in our personality’s one self must die for another to emerge?

”Can there be any doubt of Melville’s superb understanding of the presence and the power of unconscious motivation?” he asks. ”May it not be more accurate to say that Freud was a post-Melvillean than to say that Melville was a pre-Freudian?” Professor Edwin S. Schneidman, quoted in NewYork Times

Death Drive

In the context of the book (Moby Dick) Ahab of course has a much darker psychoanalytic parallel that of the ‘death drive’ the impulse inert in all of us to want for our own annihilation,

“In classical Freudian psychoanalytic theory, the death drive (German: Todestrieb) is the drive toward death and self-destruction. It was originally proposed by Sabina Spielrein in her paper “Destruction as the Cause of Coming Into Being” Spielrein, Sabina (April 1994). “Destruction as the Cause of Coming Into Being”. Journal of Analytical Psychology.

Back to Nothingness, Max Klinger

Again Klinger’s work expresses a parallel in his image ‘Back to Nothingness’ the limp body is not ascending to another life but is being reclaimed by a personification of the void, something like falling asleep but more like falling away. Clearly there was something in zeitgeist which prompted Sabina Spielrein and both men to explore these notions,

“The death drive opposes Eros, the tendency toward survival, propagation, sex, and other creative, life-producing drives. The death drive is sometimes referred to as “Thanatos” in post-Freudian thought, complementing “Eros”, although this term was not used in Freud’s own work, being rather introduced by one of Freud’s followers, Wilhelm Stekel,” Freud and His Followers. Paul Roazen. NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975,

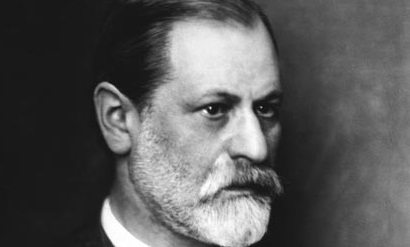

Following the barbarism of World War One and the rising antisemitism and general tensions leading to the second world war, it must seemed deeply disappointing to Freud that the idea of the death drive was so resisted,

“For the twenty-first century, “the death drive today […] remains a highly controversial theory for many psychoanalysts […] [almost] as many opinions as there are psychoanalysts”Jean-Michel Quinodoz, Reading Freud (London, 2005), p. 193.

Freud 1900 Vienna

What better proof than all the self destructive calamities of history? and, the then present context of nationalistic violence and war mongering,

“The assumption of the existence of an instinct of death or destruction has met with resistance even in analytic circles” Freud, Civilization, p. 310.

A better understanding of the function of our unconscious minds can help us to withstand destructive tendencies and recognise the traits of repression which lead us away from it. By looking at the work of Klinger we have an often neglected insight into the ideas forming in the late 19th and early 20th century which Freud would describe so persuasively in his work.

Klinger is of course a subject in his own right and cannot be reduced to, or explained away via psychoanallysis but also it would be faluse to seperate him from the forming of these ideas and his part in bringing them into culture through his potent works.

Notes/references

[1] unheimlich: or Uncanny was later elaborated on and developed by Sigmund Freud in his 1919 essay “The Uncanny”, which also draws on the work of Hoffmann (whom Freud refers to as the “unrivalled master of the uncanny in literature”). However, he criticizes Jentsch’s belief that Olympia is the central uncanny element in the story (“The Sandman”): I cannot think – and I hope most readers of the story will agree with me – that the theme of the doll Olympia, who is to all appearances a living being, is by any means the only, or indeed the most important, element that must be held responsible for the quite unparalleled atmosphere of uncanniness evoked by the story. Freud, Sigmund (1919). “Das Unheimliche”

Header Image: Detail of ‘Night, from the portfolio On Death, Part One, Opus XI’, Max Klinger, 1897

______________________________________________

Salsbury, Britany. “The Graphic Art of Max Klinger.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/maxk/hd_maxk.htm (March 2016)

Biography: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Max-Klinger

American Psychiatric Association, ed. (2013). “Fetishistic Disorder, 302.81 (F65.0)”. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Publishing.

Michael Eden is an artist and researcher working in London and the south east, his artistic practice is concentrated on painting and he divides his time between this and lecturing in art history and contextual studies.