Conceptual artist. Photographer. Painter. Matt Saunders (born 1975, Tacoma, Washington) lives between New York City, Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he currently teaches at Harvard University, and Berlin, Germany. His challenging work pushes the boundaries of artistic media by enacting painting as a time-based and transitive medium.

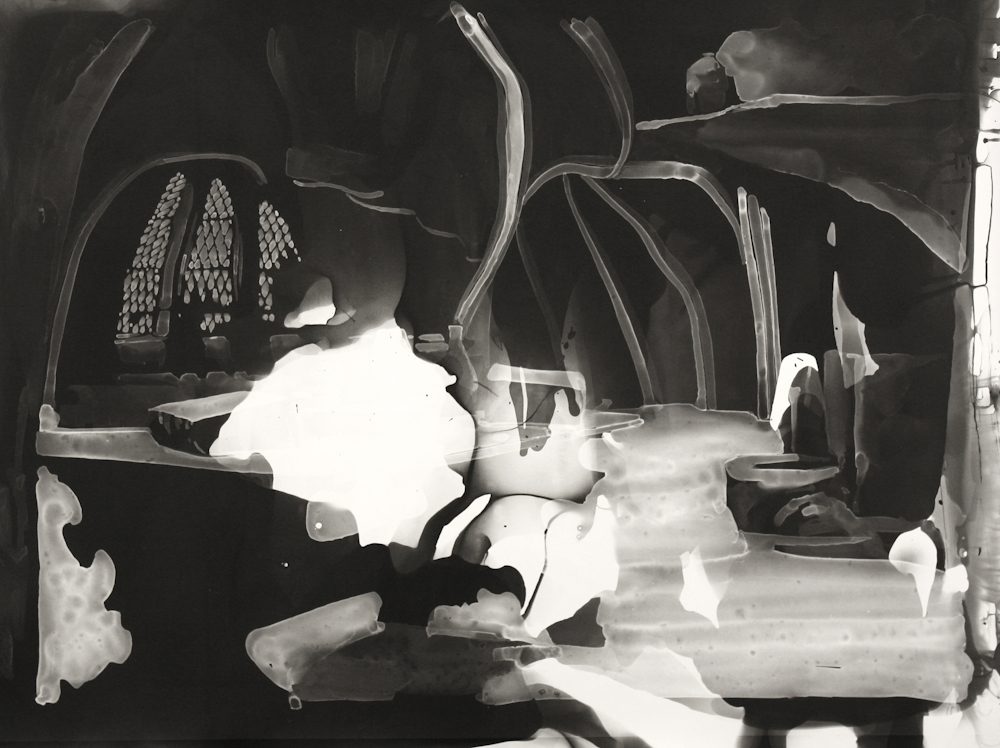

Saunders’ camera-less photography, multi-screen animation and innovative painting and printmaking processes create haunting portraits and landscapes (the imagery culled from a myriad of sources including avant-garde cinema and found photographs) and moving-image works, explores the fleetingness, mobility and affective power of images.

In researching Trebuchet’s article on his work Saunders’ gave us an insightful interview into his process.

You’ve once described photography as speculative, can you expand on what that means to you? At first glance, your photographs seem factual/the opposite of speculative?

My intimate relationship with photography is based in the photochemical darkroom. I think of it in terms of a series of procedures: setting up paper, dealing with the “negative”, the settings on the enlarger, the moment of exposure, the steps of development, the weeks and months outside of the darkroom in which I pin up dozens — if not hundreds — of prints and see what’s there and make up my mind. Each of the processes is a little open-ended. This gets into my relationship with painting and what felt so exciting about starting to work with the two mediums in tandem.

As I often say, when I finish working on a painting, it’s still only the potential for a work. I take it to the darkroom and see what I can make with it. Often, I’m wrong. Canvases I expect to be interesting turn out to be dead, while at other times, weird things come to life. For me, the photographic darkroom is the space where I bring all these things together and see how they interact and where they can arrive; and the photographs I make are the speculative objects that result from that search. It is like looking into possible future pictures.

Why do you use existing photographic material over recreating it?

Do you mean why do I work almost always from films and photographs and not directly from life? The truth is that I almost never have a camera negative in my work, so essentially, every image has been remade by hand-drawing. But it’s true that it’s almost always from a photographic source.

My answers to this may seem overly simple. I’m fascinated by photography and film, which is essentially a four-dimensional photograph, because some of the uncanny and emotionally evocative qualities of repetition, distance (from the source), surface and projection become apparent in this way. My imagination lives in this space. And photographs are a way of looking out at the world, whether they’re found images or whether I made them myself.

You use photography less as a technique than as a meta-narrative in itself. What are some of the assumptions about photography that you use in your work? Claims like the one that photography is a realist depiction of an event; or that altered photographs are no longer ‘photography’, good photography creates icons, etc.

A meta-narrative is a good way of putting it. Very early in my career I would say that I used films as a through-line for thinking and experience in the way that stories and books and published ideas functioned for previous generations. That seemed like the inheritance of the 20th century. Let me back up and clarify that every time I say film, I’m thinking of it as a kind of photograph.). There is also the narrative of the medium itself, which is very important for me. I am clearly interested in early photographic techniques, the odd infancy of the form before the materials became more fixed. You could also say that a lot of my work is empowered by the end of the analogue era. Photographic paper is outdated technology. I can buy it and misuse it “”as a painter”” and don’t have to work correctly “”as a photographer”. So there are meta-narratives of invention and obsolescence that book-end the history of analogue photography.

Photography is caught up with conversations about indexicality and truth. I’m young enough to have never really had much traction with the belief in the “truth” of photography, but I am very moved by the “space” of photography. It is such a powerful cultural form and still carries all that evidentiary promise, even if we know it’s corruptible. The impulse to pick up these materials in the first place was about getting into that space, making marks that could live beneath that smooth surface.

In the Hertha Thiele series you seem interested in the construction of icons and celebrity? Is that still the case? How did that period inform where you are now?

Movies have been a constant in my work, and I guess some variations of how performance intersects with image recur. I like to look at paintings that way too — the painter’s performance and also the subject’s.

My earliest paintings looked at passages of performance (e.g. Joe Dalessandro shaving, or Holly Woodlawn fussing with her face, or Udo Kier applying makeup) as images caught in the moment, endlessly repeatable and full of aura. From there I got into thinking about the performance of life and how a life registers or doesn’t register in the world of images. This moment you’re talking about — Hertha Thiele and Asta Nielsen among others, but especially Thiele — is about the image life cycle of icons and the idea of celebrity. I was thinking about the way their image lived, what it meant, how it was formed. There was an intense focus on those topics for a few years. I don’t think they left my practice. I can certainly point to examples of both performance and celebrity up to the current day — but I think they’ve played out in more abstract and interwoven ways.

My work about the flooding of Paris, for instance, thinks about the construction of that event as an image. Since Hertha Thiele, my work has gone into abstraction and landscape, and I’ve been thinking more in terms of emergence (as per Bracha Ettinger). I’ve also gone a lot deeper into the possibilities of the darkroom and the interplay between painting and photography, so the mediums in my work have come forward more and more as subjects, or meta-narratives. I don’t think this is unrelated to icons.

You’ve said “Reverdy/King Hu is about giving the spectator a visual experience”. Can you talk us through your process/plan for how to hone the transmission of experience?

I liken the process of working on the videos to building a solar system with no plan. As in, things start to coalesce and then get into different orbits with each other. Unlike a normal animator I never have a storyboard. In fact, I almost never have anything but the broadest editing scheme when I start. It’s really a drawing project for much of the work. Of course, I do have determined sequences which I approach like found objects, fragments of moving images that I redraw, frame by frame, to make the more “narrative” or figurative passages. These form associations and start to talk to each other in various ways in my head as I’m working, and so I start the editing process, by assembling some of these orbiting bodies into passages of animation. The process is a lot of putting things together, watching them, reacting, changing. Once I’ve set up the installation (which is often also finalised on site) I usually spend days in there taking notes and continuing to refine and change the piece to hone the experience.

You use so many processes, how does the term ‘photographer’ resonate with you? Is it a title you still aspire to, to perfect, or is it simply a hat you wear for specific occasions?

I never really aspired to it and I’m not sure I’d use it. All these distinctions are a bit arbitrary, but in my mind a photographer is someone who works with a lens. Everything I do starts with a mark on a page or canvas (and usually a mark with a brush) so I could call myself a “painter.” But I work with photography. So you might say that I’m an artist who works with photographic materials? Something like that.

You’ve spoken about creating work that “‘Flex(es) at the seams’ – challenging the viewer with an unstable image – towards a non-superficial relationship with the image”. Can you expand on how you push stability? Perhaps starting with what you see as the stability of certain visual experiences.

A tough question to answer as so many things come up for me. The easiest answer is to use the example of the animations, which starts with quite simple things, like having images behind and in front and all around, so there is no privileged viewing position. You have to walk and look while you’re moving. That’s not profound. But I also think about confusing what’s front and what’s back. Or when the image passes through a very diaphanous screen and also appears on the wall or the floor, to question which expression is privileged. I play with things moving too fast, or else I very frequently introduce strobing and inversions so the image is like flashing out or kicking every other frame. I’d argue in the photo works that I veer towards an aesthetic of change, motion, blur, contingency, ephemerality.

You’ve mentioned that “Pictures and materials being inseparable” but aren’t you ‘pushing them apart’? Can you give some examples where you’ve worked against the suppositions posed by certain materials?

The things many of my materials assume or even “ask for” may be counteracted in the work. For instance, the reproducibility of the photos. Or the painting. Besides all the inversions of colour, there is the fact that what the paint is being asked to do is to be transparent. What matters is seeing through (the light passing through) and not seeing the thing itself. When I talk about them being inseparable, the example that comes to mind is when: brightness or darkness are determined by the opacity of the pigment or the thickness of the paint. The ways of working also blend qualities, like a liquid mark ends up reading like liquid light. I think there is more to say about this, but I don’t want to get sidetracked into too many small technical examples, as the metaphorical aspects are also important.

By “metaphorical” I am thinking about how I see people and identities as always some kind of performance. I think people manifest themselves and there is something to the idea that any picture you see of mine is a material picture. An image is given substance, whether it is in a glossy or a matte photograph, whether in paint or in ink. Which says something about how I think about the subjects.

When you meet someone in-person, there are all these material realities — the air in the room, the shine on their skin — it’s always an encounter, and that encounter is embodied, on both parts. I may “meet” the same character in my work again and again, but they’ve got different qualities inseparable from their materials. For example, the two different versions I made of “Back,” which is the actress Kitty Winn seen from behind in a red coat, were painted more or less simultaneously, but one is on glue-primed linen while the other is on unprimed fabric (so the paint soaked into the threads like dye). Both are printed as photographs in the same way, but they come out quite differently, all because of the ways the image is embodied. You could compare this to “Door” which is also Kitty, but there the work, the fabric-ness, is even more present.

I don’t just mean the materials of photography, as all of my photographs are essentially photograms (with all their indexical quality) of materials like paint, fabric, ink or plastic. There is no image except as it is held in (or built by) these materials, and you can’t think of one without the other. Even with the photo prints I try very hard never to have them displayed in a way that underplays their materiality. For example, not matted in frames in a “neutral” way. In fact, I often prefer showing the photographs hanging loose, so aspects like the way they hang, the way they curl, are part of the work. I don’t like how my work reproduces digitally. For my recent book I went to press in Ghent just to try as best I could to get the printed reproductions to feel as much as possible like the photographs. As you say, the pieces work against the take-for-granted ideas of the materials, but at the same time are still very material.

Photography is about time (exposure), is that a material in your work?

Very much so. There are those crepuscular Hertha Thiele profile prints that have hours-long exposure times. There are so many that are about the 20 seconds of exposure time and how the air moved in the room at that moment. The videos too, obviously. Time is so central to the making of the work and I sometimes foster a bodily, not mechanical, relationship to it (say, by counting down the exposure myself rather than using a timer).

In your Sleep series you talk about the nature of sequence, progress, cycles and circles. Are you expressing something about the narratives around time, within a medium that has a relationship of time? What is the frisson between those things as a subject?

There was also a quality in that early show of false simultaneity. All these images from different eras all in a common dream, all asleep at once. You probably heard or read me say this somewhere, but until I saw the Warhol film (Sleep) I thought it was all about unedited, straightforward time. But of course, it’s completely edited together into that illusion, which kind of doesn’t work. The question of time (and simultaneity) has always fascinated me in history painting, where every detail is instantaneous in the illusion, but seen by the viewer in time.

You sometimes use animated flashing images; what does the white/black contrast indicate? Is it to highlight the materiality of the screen and canvas? But is it also highlighting the ‘lifecycle of an image’ from the negative to print?

I think all of the above. The positive-negative is something I think about but care less about. The flashing first started as materiality, exactly as you say. I wanted to show the videos in lit rooms but somehow it was too easy for them to become recessive… to fall backwards into image. I wanted them to kick back — to keep punching forwards and proclaiming “I am light! I am in the room!” Like a flow in and a flow out, constantly reversing. I like the feeling of the projected image because it is more present, more visceral that way.

You seem to have an exploratory relationship with how a ‘photo’ reacts to the print medium. Moreover, you often talk about painting in your work. Can you expand on what that means?

When I was making straightforward paintings, I always wanted my paintings to be folding back into themselves, engaging with the ground. (I wonder if this had to do with the influence of the seamless-object quality of photography.) I would paint on the back side of sheets of plastic, etc., so even then there was a tendency towards transformation and reversal in making the image. It was pretty natural, then, when I started using my paintings as negatives.

Later, when I started working with the print shop of Niels Borch Jensen, we found ways to work with printmaking materials kind of like photography — for instance, emphasising the time-based aspects of how the image is “developed” in the acid bath. Rather than putting light through my brushstrokes, like I did in the darkroom, this let me work in a slightly more straightforward “painterly” way (brushstrokes on an opaque surface) but still use the painted image (I mean painted with ground on the plate) as the starting point for a time-based process.

You talk about using ‘uncertainty’ in process, aren’t all artists working towards a surety of transmission?

Absolutely not. My pet peeve with paintings I find dull is this: make a mark, make a mark, make a mark until the image is complete, then you’re done. To me, there is no point in making an image as an object (as a painting) unless it gets into an interesting tension between, say, the desire to resolve optically and the desire to resolve physically.

I’m into the glitch or the static or the reverb as a sign of transmission, an articulation that things are in motion and never arrive at a destination exactly how they were when they left their origin. I worry that anything less is just illustration.

Clarity of purpose is good. And I like artists with passion and urgency and clear-eyed thinking. I guess my clear thinking is to involve the materials in a process that always translates intention through the conditions of making. Does that make sense?

Given that your work almost encourages a technical reading over visual immediacy, do you see content as part of the technical process, almost semiotically?

That is a really wonderful way to summarise it. I will have to quote you! You said it better than me. I’m not sure how to expand on this. Yes I am interested in the circulation, reception and emotional impact of image (as a nexus of comprehending activities). I guess if I think about a performance/image capture in a film, that exists as a documentary record on the filmstrip, is activated by the beam of light projecting it, but only becomes a resonant image when it lands with a viewer. There is a technical conversation there about the “medium” of producing effect. And yes, I think about stories and content as a kind of medium in their own right.

There appear to be traces of Warhol and Walter Benjamin in your work. What does reproduction mean to you?

I’m influenced by David Joselit’s idea of buzz and the increased value produced by circulating reproductions, and of course Hito Steyerl and the idea of the “poor image” or range and power of imperfect reproduction in circulation.

Most of all I’m influenced by landing in the East Village when I first came to New York in the late 1990s and going daily to the legendary video rental store, Mondo Kims. I was desperate to get in touch with the history of the place (hence all the obsessive tracking down of Warhol films, etc.) and I would watch the tapes again and again. Repetition was alway empowering, exciting, and emotional. Of course, we were steeped in Benjamin, excited by Warhol, coming of age in America at the start of the internet (but pre-social media) so endless repetition (and circulation) has a particular flavour of experience at that time. I guess another way of saying it is that repetition has something to do with encounters.

One of my favourite little essays, I often say, is the text Rainer Werner Fassbinder wrote when he started work on Berlin Alexanderplatz. He talked about reading that book at different times in his life and how it resonated differently. We all know that experience. There is power to the return of an image. And also curiosity in returning to something again and again. When I am interested in a subject or a source, I tend to paint it again and again, just circling it, trying to understand every angle. With photography, I’ve liberated my paintings for myself (and from myself). I’ll finish a painted “negative” and then, through photography, I examine it and examine it. It sort of opens up dozens of potential futures, potential readings, potential energies.

When I talk about Benjamin and reproduction in my teaching, we always bottom out in a 20th-Century idea based on printmaking and printed photographs, but I realise in answering this question that I should work harder to connect this to the dynamic, moving-image based type of reproduction that has filled the life and imagination of my generation.

In a talk you gave for the University at Buffalo (State University of New York) the topic of gender came up but then segued into ‘transformation’. A loaded contemporary topic, and one that through your work suggests that something isn’t essential but defined through experience/interactions? But perhaps this is overstating the connection.

Not at all! Gender and questioning the performance and formation of those identities was at the front of my mind 20 years ago. Other subjects took the front of the stage, but it never really left.

Since I’ve started teaching, I’ve been so in touch with the urgency again now about defining gender, and I confess I’ve been a bit troubled and mystified by my students’ desire to define things in essentialist terms. I always saw gender expression as one of those wonderful areas of potential play and transformation. It’s so clear to me that it’s formed in networks of experience. I would say that to connect that to the chains of transformation in my work and my processes is very perceptive and true.

If I might summarise your approach as ‘outcome embedded in the process but revealing types of processes that go beyond representing the already represented’, would this be the rosetta stone for diving into your work?

I love that! Yes. That’s a beautiful formulation. Brilliant!

Matt Saunders is represented by Marian Goodman Gallery

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle