[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]O[/dropcap]n April 21st this year, artist Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930, Falentos – 2017, Warsaw) passed away.

Abakanowicz was a sculptor and textile artist whose extraordinary talent attracted the attention of the art elite and who, having broken restrictive boundaries, engaged in free creative work and acquired world recognition despite post-war Poland’s status as part of the totalitarian communist block.

Time sweeps events into oblivion and memories aren’t an exception. The author of these lines first spent time in the company of the Polish artist during the founding of the Europos Parkas Museum near Vilnius in Lithuania. Our co-operation on the implementation of two Abakanowicz pieces of art lasted more than a decade.

The vision of the museum – to create a modern art museum in a marshy forest in Vilnius that would present works of the world’s most famous artists, served as the motive to invite Abakanowicz to take part in the project. I presented my concept for the open-air museum in a letter, and after some time I received a fax reply in which she said she would be really interested, but would first like to visit Europos Parkas.

I met Magdalena Abakanowicz at Vilnius airport in 1997. A world-calibre artist dressed in ordinary dark sports clothes travelled to an unknown destination and had no idea what to expect in a country that had spent long decades on an even tighter chain serving the Soviet system.

I presented her with a flower; this caught her by surprise and she asked me not to do it again.

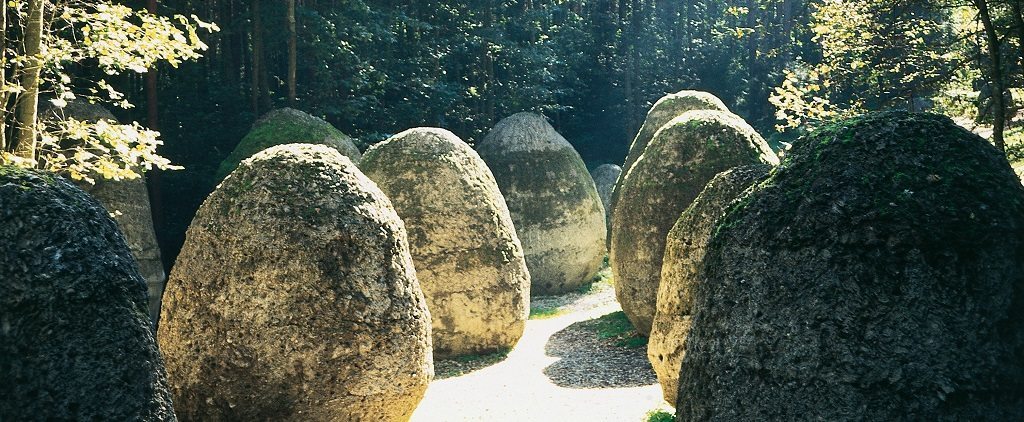

We had had preliminary discussion of the contours of the piece of art that would be erected in Europos Parkas. The original idea was that four or five egg-shaped boulders (abakans) would be incorporated into the natural environment of the museum. Abakanowicz picked the most remote of my proposed sites: a marshy hollow with springs running approximately half-a-meter below ground surface.

The ideas of the artist evolved as she saw the scope of Europos Parkas – the piece of art “grew” from a few forms into more than twenty. Abakanowicz wanted the artificial forms to resemble natural limestone as much as possible. By way of example, she provided an image of her work in the sculpture garden of Jerusalem museum.

We had to find a technology to give the surface of monolithic concrete a look characteristic of a split stone surface, and preserve the firmness of the concrete at the same time. When experimenting, instead of using the services of builders, we hired unemployed persons who weren’t afraid to do things “differently”. The works continued for approximately one year. On one occasion Abakanowicz arrived at Europos Parkas in late Autumn. It began to snow. She asked to travel back to Warsaw immediately because she hadn’t thought about the piece of art in the context of snow.

The site was a marshy one, therefore we even had to build a road to allow access for lifting machinery (the biggest concrete “abacans” weigh more than a dozen tonnes) as well as trucks carrying sand and gravel. The infrastructure created for the implementation of the work was eventually covered with dirt so that it wouldn’t interfere with the aura of the natural environment.

Magdalena Abakanowicz ‘Space of Unknown Growth’, Europos Parkas, Lithuania

When we eventually managed to create the work and displayed it to Magdalena, she was silent for a long time, placed her hand on me and said: “You made more than I could have expected. This is extraordinary. The shapes will stay as they were cast, I’ll only make some changes in the composition.”

When the sculpture was finished, we stayed in contact. We sometimes exchanged letters and sent her pictures of the work. She also liked the postcard with the view in winter, and asked us for more copies so that she could send them as New Year cards.

The Conjuror by M. Abakanowicz that appeared in Europos Parkas in 2009, twelve years after her first visit, is quite different. When erecting the piece we had a lot of contact, discussions, even negotiations. The initial idea of a bird-shaped stainless steel sculpture was abandoned and gravitated towards a piece with a more prominently expressed touch of the artist. The artist was present at the birth of her bronze sculptures, shaping the folds of the cloth used in the process of casting bronze from forms.

Abakanowicz’s residence was at Birch Street, Warsaw, a tranquil street in a prestigious neighbourhood. According to her own story, she once had a dream to set up a sculpture park there but never managed to overcome bureaucratic obstacles. In my opinion, one of the reasons why the artist showed such exceptional interest in Lithuania, was that in Europos Parkas she saw her unfulfilled dream. I recall she was impressed with the then skyscraper-free city of Vilnius, but when she visited a decade later, she became very sad and expressed her regret that the human-scale cityscape was drastically disfigured. She had though that Lithuanians were smarter than that.

Once during a discussion about art spaces, the artist said she often considered what made it possible to create objects like Europos Parkas in post-communist Lithuania, and answered her own question by opining that it was determination: when you are bound by a rural location, and in part by the low profile of your country, you can direct all you energy towards putting your vision into life. At the same time, you have to take full responsibility for the result, without waiting for someone to help, find solutions or carry out the works. Determination in space offers an opportunity to perfect yourself and grow stronger.

M. Abakanowicz was a highly-concentrated and targeted personality who didn’t waste her time. She didn’t visit other artists’ exhibitions and dedicated all of her time to her creative work. Her husband understood her very well and helped his talented spouse: he dealt with technical and engineering aspects of erecting her works.

We used to refer to Magdalena as the World Ambassador of Europos Parkas. One American artist once told me about an event during the opening of M. Abakanowicz exhibition in a New York museum. Abakanowicz was tired and didn’t communicate with the guests, but the artist mustered up the courage to approach her and tell her that she had visited Europos Parkas. She was the only one to whom M. Abakanowicz replied, by saying that it was a truly grand project.

Magdalena Abakanowicz will forever remain alive in warm memories and amazing multidimensional pieces of art. Abakanowicz was remarkable from birth, partly because the first three letters of her surname (“aba”) granted her the privilege of always being on page one of books on modern art. The beautiful and meaningful cultural cooperation between Lithuania and Poland has a sustainable result – thousands of art fans from all over the World admire the works by Magdalena Abakanowicz in Europos Parkas every year.