“Cameras are the antidote and the disease, a means of appropriating reality and a means of making it obsolete.”

-Susan Sontag, On Photography, 1977.

‘As widely practiced an amusement as sex and dancing’ image-making is central to our lives. Estimates indicate in 2018, there were 1 trillion photographs taken (Forbes, 2019) ‘Pics or it didn’t happen’ is now a common rallying cry on a night out. Images of the highlights of our lives aren’t confined to the ‘ghostly traces’ of the physical photo albums Susan Sontag discusses in On Photography, but rather live on the internet for our friends, but also total strangers, to like and comment on. Experiences: holidays, weddings, anniversaries, and birthdays are staged as part of a perfectly curated and self-conscious projection of ourselves.

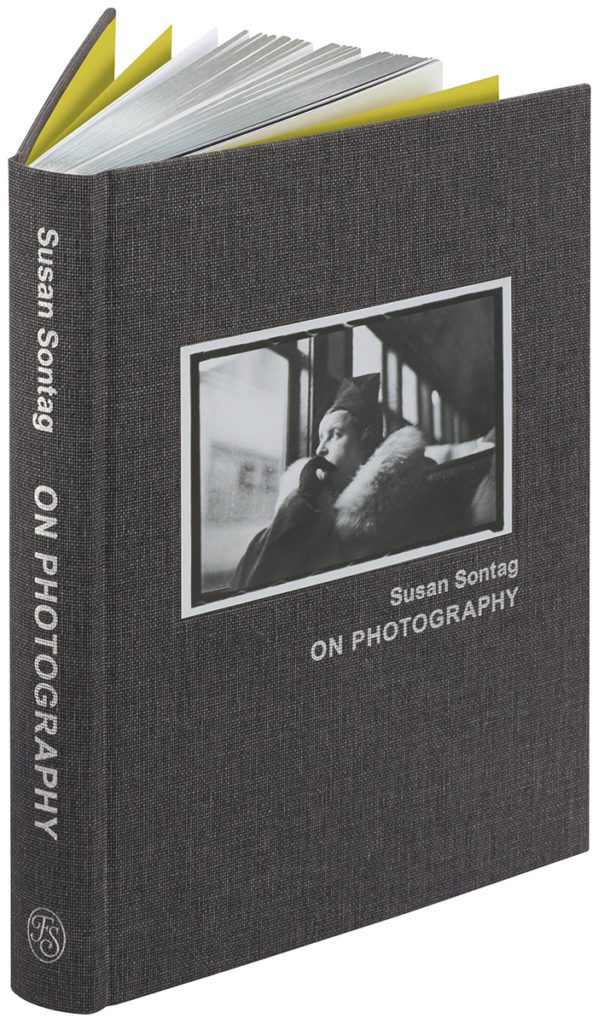

Almost 50 years following its publication, On Photography still offers an insightful and articulate account of our relationship with this medium, and how the increasing accessibility of photography since its inception has unilaterally changed our relationship with the world around us. Perhaps it is for this reason that the Folio Society has decided now is the time to bring out the first illustrated edition of On Photography. This edition is being introduced by Mia Fineman, curator of photography at The Met and a leading expert on Sontag’s writing who spoke to Trebuchet about the release

What makes On Photography worthy of so much continued discussion so long after its release?

I think the number one reason Sontag’s On Photography is worthy of continued discussion nearly fifty years after its initial publication is that it’s a great piece of writing. Sontag was a consummate prose stylist, her sentences and paragraphs are marvels of power and concision. In their density of thought and ideas, the essays are the literary equivalent of 100-proof whiskey, yet reading them feels more like drinking champagne.

I’m amazingly lucky to have a career in which I get paid to look at, think about, write about, and share photographs with the general public. Ever since I first read Sontag’s On Photography in college, the book has been a touchstone for me, a model of writing that is both rigorous and accessible—a form of criticism that addresses the present moment while ranging knowledgeably across the entire history of the medium. I’ve always appreciated that Sontag was a generalist and her engagement with photography was propelled by a kind of obsession. I find that her love-hate relationship with the medium makes the essays very exciting to read.

I think modern readers will find many of Sontag’s observations about photography not only relevant but incredibly prescient. For example, she argued that photography encourages an acquisitive relationship to the world: we see something we like, we take a picture of it, and eventually, taking a picture becomes a stand-in for direct experience. Here’s how she puts it: “A way of certifying experience, taking photographs is also a way of refusing it—by limiting experience to a search for the photogenic, by converting experience into an image, a souvenir.” Sontag recognized this tendency in its nascent form in tourist photography, but the addictive consumerist qualities of participation and exotic colonialism (aspects of tourism) via the act of ‘taking a picture’ become greatly magnified in the age of smartphones and social media.

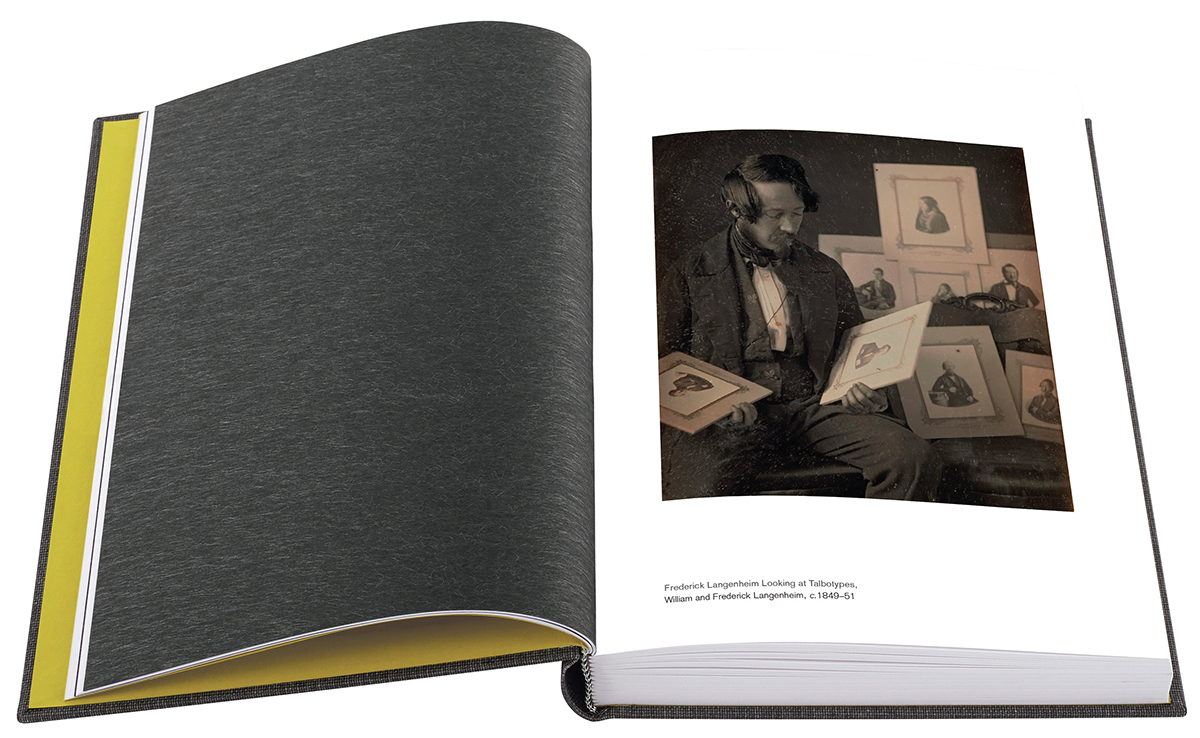

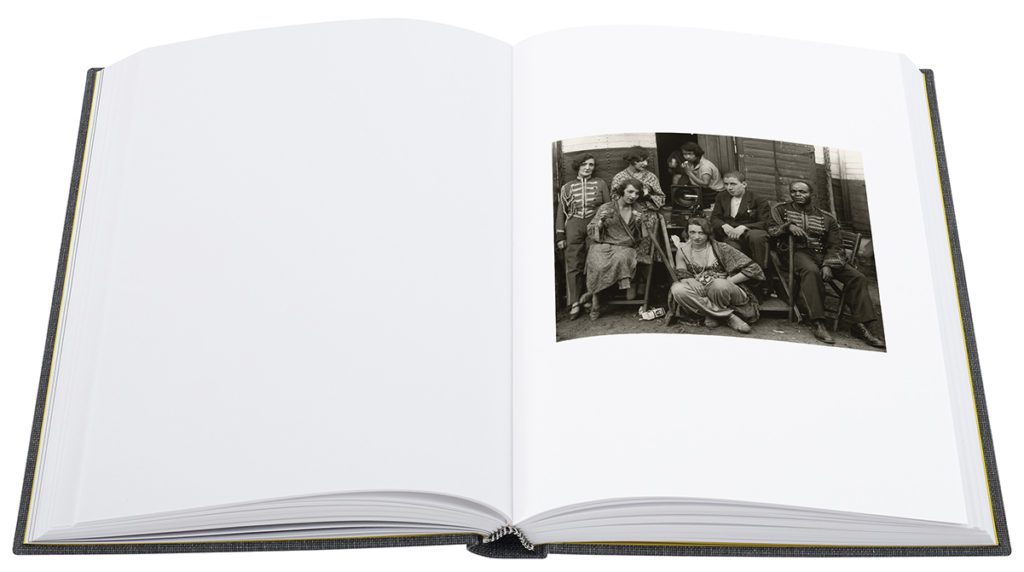

I think Sontag was being somewhat disingenuous when she said the book isn’t about photography. It’s true that she doesn’t spend much time analysing individual images, but mostly she didn’t want to be pigeonholed as a photography critic because she found the existing discourse lacking in seriousness. The images in the new Folio Society edition help to anchor and enliven the text by providing visual references that correspond to her discussions of particular photographs or types of images, even if they are only mentioned in passing. One could Google each of the photographs she talks about, but it’s much more pleasurable to see them on the printed page.

Photographers have famously had a prickly relationship with On Photography – do you feel the reception to Sontag’s analysis is warmer today than it was at its release?

When On Photography was first released in the 1970s, the medium was still struggling to establish itself as an art form and there was a pervasive sense of embattlement and defensiveness among photographers, curators, and critics. Now that the medium is unequivocally recognized as an art form both institutionally and in the marketplace, photographers and their advocates are much less sensitive about Sontag’s analysis of the camera’s adverse effects on human consciousness. Today I’d say On Photography is regarded as a classic text rather than as a provocation.

One of the primary fascinations but also critiques Sontag has with photography is its exploitative nature. Do you feel the ethics between photographer and subject have evolved since On Photography was first published?

Sontag wrote brilliantly about the complex ethics of photography: the camera’s inherent voyeurism and aggression, the power imbalance between photographer and subject, and most famously, and the numbing effects of viewing images of war and atrocity. Even in the 1970s, documentary photographers and photojournalists were mindful of the medium’s potential for exploitation and often tried to mediate the balance of power, for example, by including first-person testimony from their subjects alongside the images. Today most photographers are exquisitely sensitive to the ethical issues of photographing people with or without their consent—and social media offers a robust forum for real-time public discussion of these questions.

For readers new and old, this edition offers the ever-prescient prose of Sontag with the stylistic panache expected from the Folio Society. The key is the selection of images, they anchor the text and reference the history of photography critical to Sontag’s analysis. Images do not crowd the text – words still do the heavy lifting while images serve to articulate the themes.

An excuse to pick up On Photography again should be applauded. Sontag’s analysis of our personal relationship with photography feels especially prescient in an epoch where easy access to photography has allowed the individual to commodify their lived experiences. It still stands up as a must-read, not limited to art criticism but as a wider study of human behavior.

The Folio Society edition of Susan Sontag’s On Photography, introduced by Mia Fineman, is exclusively available from foliosociety.com/photography.

Featured Image: The Folio Edition of Susan Sontag’s On Photography, © The Folio Society.

Ruth O’Sullivan is a writer and curator. Her work explores the impact of digital technologies on contemporary art practices and challenging gender disparity within the visual arts.