What is a person?

The book opens with a philosophical pursuit of personal identity. Briefly, what is it to be a person, in general; and then, what is it to be a particular person? Piper uses analogies and images to show how we are formed as persons, and, how that formation can take different paths. A person is likened to a layered vegetable – she uses a sprout, Wittgenstein uses an onion – and she talks of the outer leaves protecting the inner core. Interestingly, Wittgenstein’s use of an onion is to show that there is no centre. When you peel away the layers of an onion you are left with nothing.

The second analogy is with a rolled piece of fabric whose constant turning adds layers so that the centre is protected. This image is developed in terms of the outer layers being the interface between the self and the outside world, so that the latest the newest experiences show up most vividly and most clearly, the centre getting more and more hidden, deeper inside.

The socially constructed self

This provides a problem of which Piper is aware. If the self is continually wrapped in layer upon layer, we might think that it becomes less important than the exterior ‘apparent’ layer. Here she shows her awareness of the socially constructed self. The social fabric into which we are woven, to use her analogy, can be thought to define, outline, and, ultimately, confine the self. In this she recognises the constitution of a person through her social extension. There are those, however, who,

‘crave transcendence through escape rather than through the binding ties of community; and so present unremitting problems of authority and control for those around them. But there is nothing anyone can do about a particular person’s mode of preparation for flight, including the person herself. You just have to remember what is deep inside them, inside all of them.’

Piper is an artist as well as a philosopher. The book is interspersed with poems overwriting images she has made. In Vulnerable (1993) uses the thoughts she has on personal identity along with other thoughts on the nature of what we should be. It overlaps an earlier print, Vanilla Nightmares which uses a New York Times front page with an image of South African miners suffering inhumane conditions of work. Drawn around this are the heads of Africans whose eyes are blank. The fingers of two hands support from behind the central section of the from page which has the headline, ‘Reagan Resists Sanctions, but…’ Three inset portrait photographs from the front page show Ronald Reagan, Desmond Tutu, and (I think) Richard Nixon. Below this are the trunks of naked Africans, an erection lifting its head in front of the three portraits.

Adrian Piper, Vanilla Nightmare

The utopian self

Piper imagines what life should be like. A Utopian image of a life where we do not have to repeat ourselves and in which efficiency is built into the laws of nature. After minimal effort to set ourselves up for life, we should get on with whatever we like. Bravo. Here we take off into an imagined world; but one where, like all philosophical thought experiments we return the wiser.

‘[W]ill my having repeated myself fifty times ever finally pay off?

Really, it ought to. I am morally certain that all of the stupid mistakes I have repeatedly made over the eons of lifetimes I have accumulated in learning their lessons will, in the end, have exhausted all the stupid mistakes there are to make.’

The image of the coiled fabric comes back to show itself as repression of the self, imagined, but now burdened by this particular embodiment. Why am I, me; here, and now? And here and now she takes us through the litany of corruption and abuse at which western civilization has arrived. In Mumbai a child can be bought for $7. The international child sex slavery and the weapons trade; the Catholic church and its protected abusive priests are listed amongst the incredible economic forces unleashed by the west and its ideologies.

Happiness

A family photograph shows Ms Piper as a five-year-old in 1953. She is with her parents and her uncle – all smartly dressed well-to-do, African-Americans. The photograph is taken in Washington Heights. It reveals more than the scene it depicts. The world in which Piper finds herself is not the world in this picture. For the five-year-old, it is tragic. Disappointment awaits.

Piper was brought up in a loving family in which no mention of her appearance was admitted. This, because her paternal grandmother was so extraordinarily beautiful that it caused her much misery as she grew older and began to fade. Piper, as a result of this family policy, grew up with no conception of her looks, and a Kantian adhesion to the invisibility of reason – for reason, along lines inherited from Immanuel Kant, discriminates not between black and white, between male and female, or between tall and short, for that matter. Hence, she became suited to philosophical reflection rather than the reflections provided by mirrors.

The chapter is a memoir of her family and the incredible help and support she was given. At its edges, there is foreboding. The world changes for Adrian Piper but she is defiant and resolute. Go on, she tells us, after all, the problems she faces are as nothing compared to the horrors she has alerted us to. Close the book. Read no further. But she ends with the sentence, reflecting now upon her childhood, ‘I was loved.’

We learn of a rare and valued ‘listener’. He is Phillip, a fellow art student, who took Adrian dancing and listened with quiet but critical respect to her thinking. Her parents taught her the importance of integrity – of always minding one’s words and always keeping one’s word. For Phillip as well as Adrian, the nature of language was aimed at truth, never manipulative or disingenuous. She knew him over a period of almost twenty years, until his untimely death in 1982. Here, you feel, that there is trust at the heart of the friendship these two shared. You feel the rarity of this special trust between them. Words for her colleagues became a ‘currency, although not a currency of communication.’

The problems of teaching and research in a modern institution

There is a convoluted and detailed description of the treatment Piper feels she was unjustly subjected to by her college and her colleagues. It is too personal to for the reader to arrive at an unbiased or clear or settled opinion. In part she recognises this,

‘I remember my parents staring at me in wide-eyed astonishment as I marshalled one impassioned argument after another as to why they should do yoga, take vitamins, and eat health food. At the time I had thought they were just listening intently at what I had to say.’

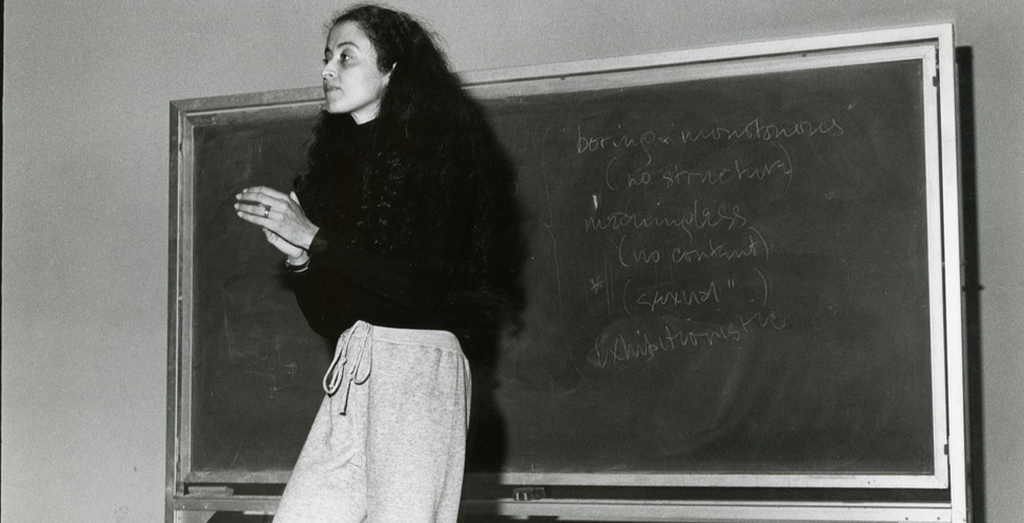

Things are not going well at college. This painful and traumatic set of experiences shows up in her artwork. A schematic drawing of three heads and gesturing hands from the mid-nineties, a ‘hear-no-evil, see-no-evil, speak-no-evil’ drawing is presented because,

‘I had no words to express the perversions of communication I was witnessing all around me: the insensate resistance to registering the import of ordinary language used in naive, forthright way; the dexterous manipulation of meaningful phrases full of profound content and good will, to denote exactly the opposite (…)’

It is the lies, the sheer ubiquity of lies, that Piper finds horrific. It is to counter these lies that she devotes her work, both as an artist and as a philosopher. She gives voice to this, not only in the memoir, but in the pieces of writing – poems, short prose pieces and writing over images – that she intersperses within the book.

There follows a disquieting description of the move made by senior colleagues at ‘The College’ to silence her and to bring about her resignation. Whatever the circumstances, the reader is left in no uncertainty, that the experience was traumatic for a young academic, trying to make her way in a very tough world.

The friendship she shared with Phillip would define her art school career. Philosophy departments are quite unlike art school. She captures this brilliantly,

‘I had worked during art school and supported myself through college as a bookkeeper, model, receptionist, and telephone operator. I already had achieved professional acceptance as an artist. In the art world at that time, working at a low-stress day job in order to maximise one’s freedom to make art was par for the course. I had initially assumed I would return to some such arrangement after graduate school, with my art making greatly enriched by my work in philosophy. All I needed from graduate school was to do that work. Unlike my classmates, I did not view it as a path to financial security or professional status.’

Berlin

Piper wraps up her life ion the US and heads for Berlin, where she rents an apartment in which to live and a loft in which she can house her archive.

Whilst much of the work is concerned with the experience of being an African American, other parts take on the wider issues of what it is to be alive at all. The artwork gives her space to work on personal issues; but it is with the broader, less subjective, issues that I think her work shines brightest. This is a moving tale – quite literally. It will be interesting to see her work now that she is released from the bureaucratic burdens and daily affairs of college life.

Escape to Berlin: A Travel Memoir. By Adrian Piper, APRA Foundation, Berlin, 2018

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.