What if the humble act of drawing didn’t just represent the landscape, but interrupted its ideological conditions of visibility?

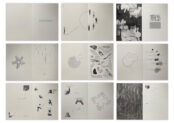

The British landscape, long cast through the visual traditions of the picturesque, the pastoral, and the imperial lens, is not neutral terrain. It is an aesthetic system, what I call the nostalgic axis, that encodes ownership, control, and coherence. My recent drawing-based research at Ashridge Estate in Hertfordshire seeks not to reframe this terrain, but to fracture it, to draw through and against it.

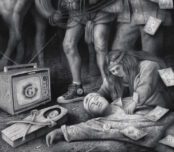

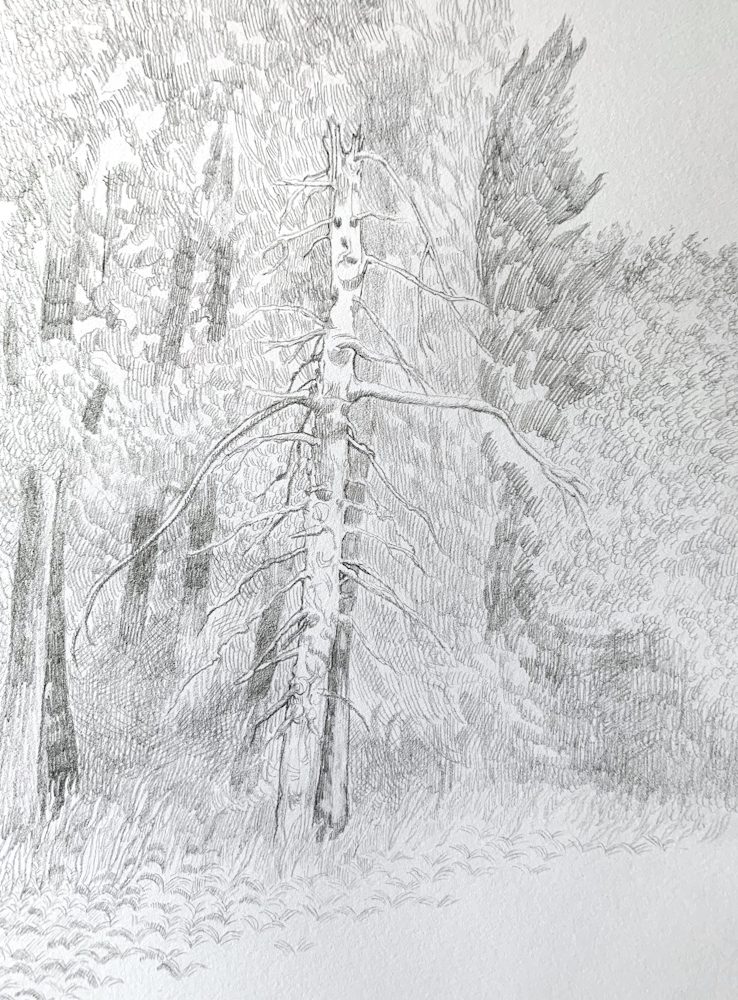

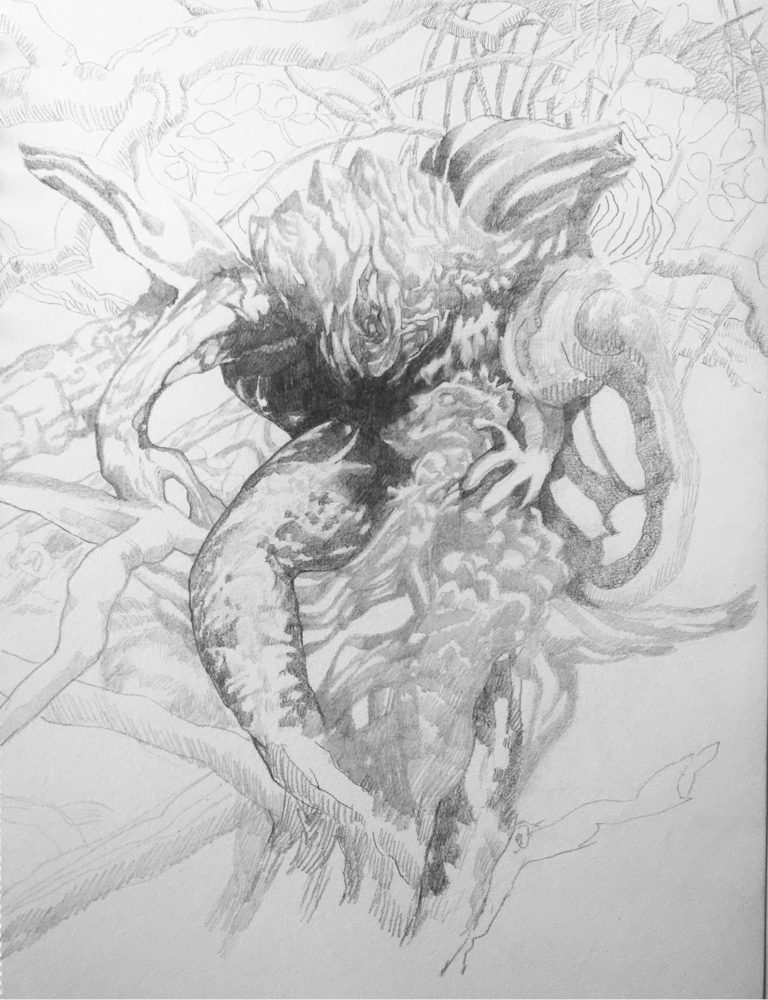

This is not landscape as view, but as ideological event. Drawing becomes a perceptual experiment: a fieldwork of the eye, hand, and body that engages with the non-representational ruptures latent in the environment. These ruptures often emerge through pareidolia. The spontaneous apprehension of agency or figuration where none is formally present. A twisted tree becomes a hunched body. A fallen branch bears a face. These moments are not fanciful projections but pre-ideological disturbances, glimpses of a perceptual substrate that resists domestication.

Pareidolia, typically dismissed as a cognitive glitch, is here reclaimed as a foundational visual faculty, an ancient mechanism that precedes and potentially undoes visual ideology. As Walter Benjamin described in his theorisation of the optical unconscious, mechanical media like photography reveal what habitual seeing occludes. Drawing, in this case, performs a similar role: it slows down vision, opening a space for those contingent perceptual events that ideology would rather smooth over.

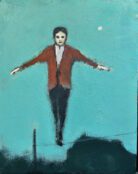

In this light, my drawing practice is not illustrative but diagrammatic, in Deleuze’s sense. It operates not as representation, but as an incision into the field of visual possibility. The diagram is a “catastrophe”, a forceful insertion of chaos that breaks with figuration and unlocks zones of pure sensation. Works such as It’s Always There and Ghost Tree emerge from these diagrammatic breaks. Their forms are not stylised interpretations of nature but encounters with the Real. What Fisher might call the eerie: a presence that shouldn’t be there, or an absence that haunts.

These eerie moments mark a critical shift in subjectivity. As Fisher wrote, the eerie “forces us to ask what kinds of agency are at work here?” In a similar way, the figures that surface in my drawings are not fully mine. They are co-productions between perceptual drift and environmental force. The agency lies not only in the hand but in the materials, in the site, in the affective thickness of a place.

This opens up the political charge of the work. The nostalgic axis functions to naturalise ideology: to make the enclosure of land, the erasure of histories, and the violence of possession seem serene and eternal. But drawing through pareidolia resists this. It refuses stability. It insists on ambivalence, disturbance, and flux. As Merleau-Ponty argues, perception is not a mirror of the world but a dynamic co-constitution of seer and seen. To draw is to enter into that unstable zone, to register, rather than resolve, the contradictions within it.

There is, then, a politics of the eerie. Of the weird. Of the unsettled. This is not the nihilistic cosmic horror of Lovecraft, but what Fisher and others have called the New Weird, an aesthetic and perceptual orientation toward that which exceeds containment. It gestures toward a rewilding of perception, a reminder that the land is not ours, not static, and never fully knowable.

Drawing, for me, becomes a technology of disobedience. It breaks with the smooth legibility of the managed landscape. It activates what Timothy Morton calls a “cognitive upgrade”, an unsettling re-tuning toward the nonhuman, the contingent, and the more-than-visual. The act of looking becomes ontologically unstable, the page a field of negotiation between attention, ideology, and emergence.

These are not artworks of fantasy. They are glimpses of another order of seeing, one that arises not through invention but through encounter. The task is not to impose form, but to recognise its eruption when the world, for a moment, looks back.

Michael Eden’s Drawing Project

Eden’s research-led practice can be viewed on Instagram @eerie__weird__axis, where he shares sketches, field notes, and pareidolic sightings from the edges of English visual order.

Michael Eden’s Drawing Research Page

Images courtesy of © Michael Eden

Michael Eden is a visual artist, researcher and writer at the University of Arts London exploring relationships between monstrosity, subjectivity and landscape representation.