Comicbook heroes are mainstream and big screen. They are the giant myths written across our lives. Run through with commercial hooks they would carry us blindly from purchase to purchase given half a pound. With an equal choice between two similar products who wouldn’t choose the one branded with greatness, the super product?

The once niche spandex-clad archetypes of Marvel and DC comics now function as central myths in Western society. Perhaps not as clearly as Churchill or Hitler but they are tools through which we work over our moralities, guiding principles, our societal trajectories. They comfort us with the idea of absolutes and the power of choice and, in doing so, infantilise us by appealing to our lowest and most servile instincts. They’re also damn good fun and allow us to break away from the lowest and most servile realities of contemporary life. An escape into the machine-language binaries of our reacting chimp and hungry reptile, emotional safe spaces of need-as-nobility (I need this for the good of humanity) and reward-as-satisfaction (closure achieved!).

However, this artful escapism into myth has an insidious infectious quality because when stories are told well we see reality in the same terms, with the characters working towards definite ends and predictable outcomes assured. The constant presentation of Superpeople is feeding the way we ennoble our societies heroes, as predatory techno-kings above the law, tax and accountability churning righteously towards better tomorrows. Or at least that’s how the macro mainstream would have them made, give them a pass, and tack on some truisms but it applies to our minor lives as well.

We live in futuristic magical times where the threat of social misstep has created an existential void where we self-police looking for dark misanthropic corners of our psyche; we act in fear of unconscious realities, paranoid dreams of guilt and hurt buried beneath layers of primary coloured situational inoffensive conformity. We are told we should have a super-clear morality unambiguous and unafraid of our now total lack of privacy. But, here they come – those feelings again. While we may have good intentions, weaponised language means that in any situation we sit between privilege and marginalisation on tilting woke scales. Our personal opinions are intersectional points of wider social/super-human forces, which, while unavoidably true, are also objectifying, anonymising and perhaps even dehumanising – our experiences minimised to emotional statistics with readymade roles, remedies and answers.

Ouch.

That we know and live through nuance is obvious, life is complex, but we desire the promised certainty all the same. And, in late capitalist society, the only crime is an unsatiated desire. Whaddaya mean you can’t get what you want? Are you an Incel? A Victim? Just what the hell is wrong with you anyway? Try harder!

Many super-hero movies play with ideas of power and responsibility refracted through archetypes who all conclude with a sort of social approbation close to a redemptive nationalism. Saving the day (never the year) the nature of power being read as a responsibility to act (for and over the weak) necessitated by endless antagonists. But fight we must, again and again, and again! Few narratives look inward and ask what the appeal is? What does the massive success of these stories say about us and what compels us to flock to its repetition?

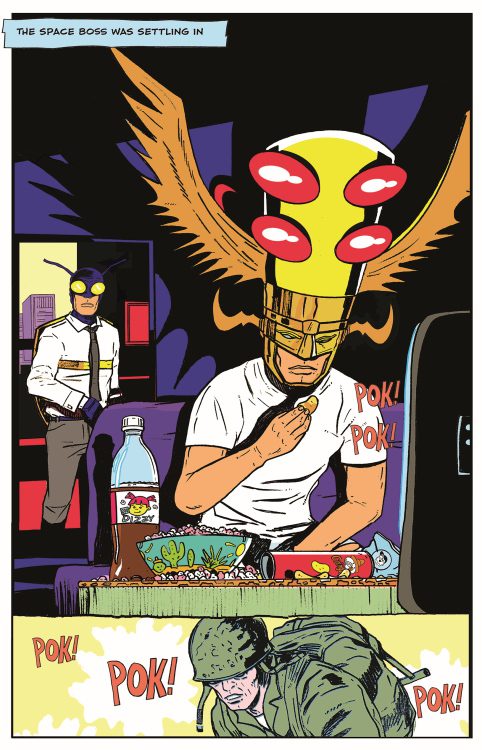

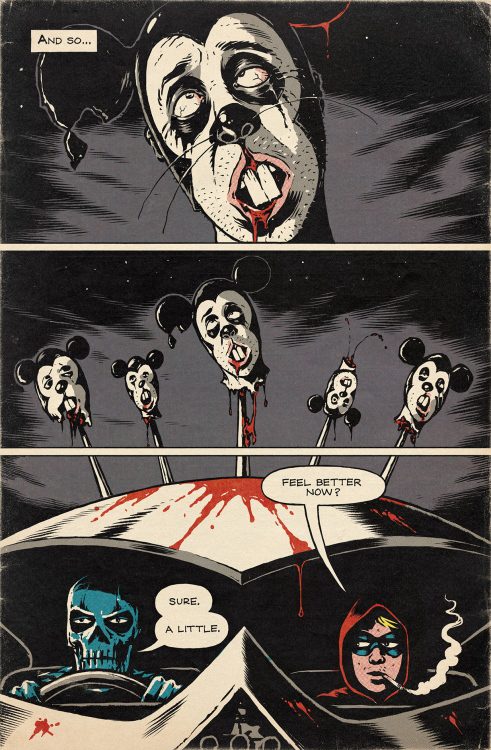

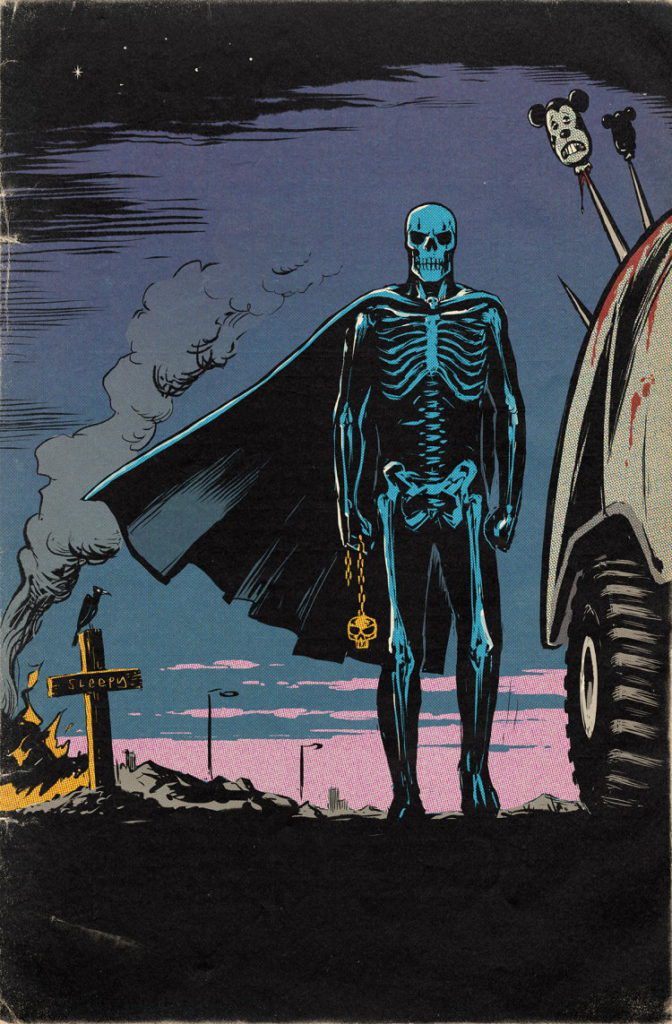

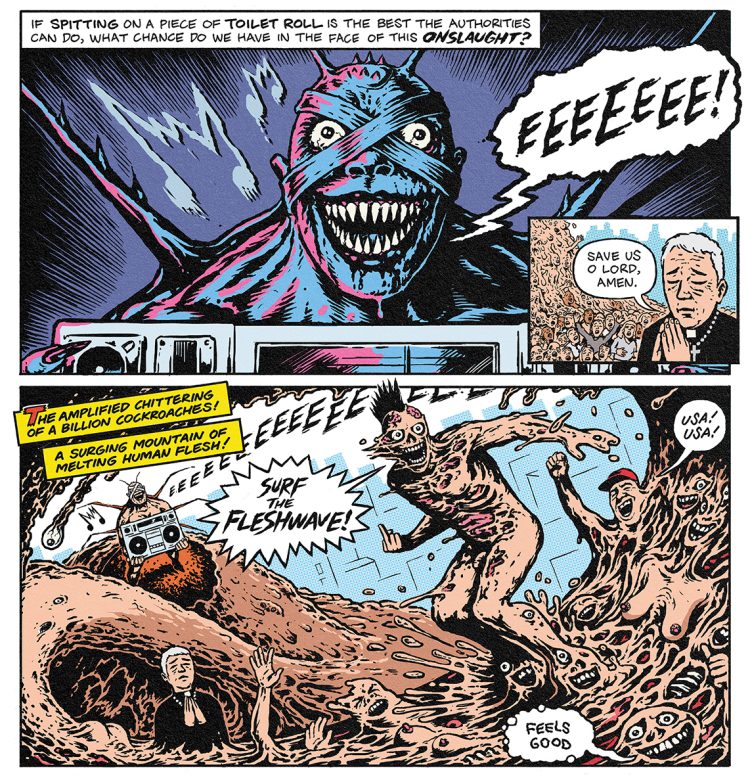

Exceptional works like Alan Moore’s Watchmen (1987) and the Amazon Series The Boys (2019) approach the complexity beneath the audience’s lust for these tropes building on philosophical investigations of thinkers like Nietzsche (Ubermensch) and Roland Barthes (Mythologies) who unlocked the intersections of social and personal need in myths of absolutist power. But what about the dark juju that feeds the ego? In Shaky Kane and Krent Able’s Kane and Able, we are given access to the basement tapes of the unconscious. We are shown how the Garmonbozia is made, sausage veins, creamed corn and all. Here the darkness, lurid weird perils, hanging closure, and edged insight are revealed as the materia prima of desire and nothing is off-limits except hype. When the obvious excesses of violence and sex are presented as worn-out tropes, we are shown much of what we’re told to want as banal pamphlets on the sticky carpet leading down the dirtiest hole of our collective set.

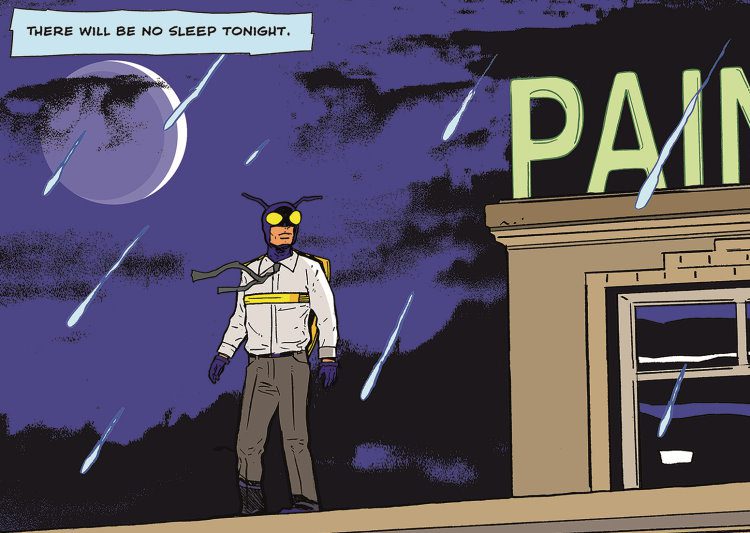

Kane and Able use the medium of comics to lampoon and deprogram the reader from superhero myth-making. Similar to how comedian Stewart Lee deconstructs the performer/audience relationship within performances, the snarling sarcasm of the Kane and Able twists the script. The Marvel and DC mythic visual language pared-back reveals the standard hero’s journey to be crumpled and compulsive, fetishistic, septic, and ultimately unsatisfying by design. They show us how mainstream stories tantalise with the saccharine violence of industrial darkness but in the end by reinforcing nuclear familiar values and homeostatic balance are both deeply conservative and dangerously false. The mainstream presumes a homogeneous balance and wholesome moral compass whereas Kane and Able shine a light directly on our shadow being, illuminating, like a Hiroshima blast, our outline, our absence, our a priori emptied-ness. We are made through stories, phenomenon is read as situation, familiar as a scenario, and made mythic as an event. In other words, we overlay what we recognise in a cohesive way on reality in order to orient what we think we want over what we think we know. The artwork and storylines of Kane and Able reflect how we piece together fragments of lives to create episodic personalities, heroes, protagonists, readers within us as a process of cognisance. The greatness of the works like this is are we are constantly reminded of the process of reading as a process of writing as we are punched through fourth, fifth, sixth walls with gleeful abandon.

The disjointed nature of this comic recreates the feeling of picking up a comic in the grey 80s when titles were often stocked out of sequence. This led to an esoteric way of reading comics where the reader would piece the basic story together from snippets and recaps. Most times, that you’d start a comic with huge gaps in the backstory created active readers who filled in the story with what they could assemble from fragments. This is sort of reading is enabled and encouraged in Kane & Abel where familiarity is assumed, and where the meta-story pulls from the base arc of all comic storylines – but horribly skewed, leering and sarcastic. We know these characters, their backstories are understood; from the repulsive pupa stage, they have emerged through tribulations with mutant allies and superpowers, all the better and noble for their humiliations and humility.

In our end-times, the ideas of an un-alloyed super-person, let alone ‘man’ are worn and wary, but these frames persist in the subjectivity of our eye’s prejudice. Rather than retreat to the suburban homily of the Daria and Harvey Pekar type comic realities, Kane and Able take the emo-invigorations of the big title millennials and say ‘Ok, kids you want the darkness. Then let’s move past ethical doubt of marvellously moody arcs a la “Am I worthy of being so powerful?” and into the nuclear lust of demonstrable power e.g. “Their heads are moist yet satisfyingly crispy… like a bat’s vagina.”

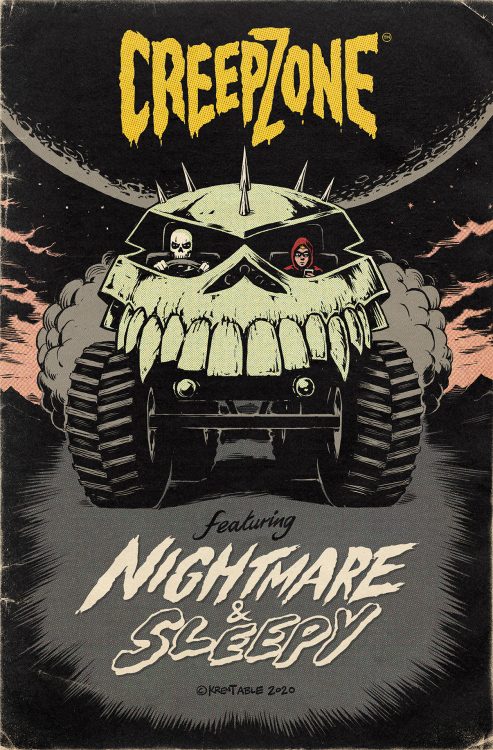

The four vignettes in this graphic novel weave a tale through the skeins of familiar tropism and repurpose the ‘comics’ material to surprise, shock, titillate and draw us into the unconscious. Stroked by sex, murder, insects, cars, and dust the Warhol-Burroughs verve of Kane’s work grinds irresistibly against the adenoidal rigour of Able’s B-movie anti-hero freakfest. Reminiscent of the Tarantino-Rodriguez’s grindhouse two-fer, the tonal differences in each artist’s stories work together in a ‘I’m sick of the world. Let’s ride it till the flavour rubs off this rubber’ way. It’s negative stuff. It’s a mean laugh at the reader and a cold laugh at themselves. Decrepit comic artists hunched behind flimsy card tables at low-end Comicons, habitually fan serving, earnest but spent, past tired of past bitternesses (there are some harrowing panels here), we are creators and we are tired.

Variously, Kane & Able lampoon the idea of literary interpretation and in one line they play through the idea of creative symbolism via a red rocket pen. Passed through many hands, it reaches the present, fully realised as an antagonist or at least a loaded McGuffin, a cocked blank, ready to shoot if only to…

There are no conclusions to this book. Beats yes. Endings perhaps. The expansive open palmed silence at the end of each story tells you a lot. It’s a deep cut for people in the know and even then probably mostly for other comic artists. The stuff not just outside the panel but off the page and in a cracked favourite cup, creator agonies that mire the pen and inker.

There is a wonderful wasteland atmosphere to the book where memetic characters, archetypes, Hollywood scenes reach a sort of entropic finality that are slowly reduced. There might be several hundred graphic novels that explore the greater detail and nuance in comic-story, but very few explore the nuts and bolts of memetic psychology, our addiction to myth. This does and it changes you, proving that there are still voices in an increasingly hackneyed medium brave enough to make potent art. Fade up to black.

Ex-London based reader of art and culture. Specialist subjects include; media, philosophy, cultural aesthetics, contemporary art and French wine. When not searching for road-worn copies of eighteenth-century travelogues he can be found loitering in the inspirational uplands of art galleries throughout Europe.