[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]C[/dropcap]reativity is expressed through process.

“The exhibition presents 50 years of British art that is generated from strict procedures. The artists make their work by following rules or by writing computer programs. They range from system-based paintings and drawings to evolving computer generated images“ – GV Art.

With several decades of reaction, opposition, revolution , classicism and rejection, the role of computers in art remains vital if slightly uncontroversial.

We now live through computers, our realities are regularly augmented, their processes have become ours, to the extent that power and influence is widely calculated on memetics and metrics. Processes themselves that have been given life through the ability of computers to crunch time and repetition.

With automatic art we’re asked to consider work by people who are using tools of repetition, which on one level isn’t that unusual in the history of art. Or life, for that matter. Habit and repetition are the hallmarks of culture, specialisation, and perhaps even knowledge itself; things can be said to take on importance through the opportunities they engender and knowledge, in an evolutionary sense, might well be the meeting of strategy and opportunity. Furthermore, the historical experiments of process art have their analogue in the rules, errors and returns of contemporary digital life.

Automatic Art: human and machine processes that make art – extended from GV Art on Vimeo.

Computers then are the relatively recent development of abstract strategies that allow us to habituate knowledge and strategy with the bonus of skipping repetition. Or so we, ideally, believe. Anyone who has used a computer knows that the reality is actually highly repetitious, though the locus of repetition is in perfecting repetitious systems of action. Rather than the actions themselves, we learn from their doings.

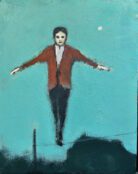

If the ‘automatic’ in automatic art is the output not the thought, what then are we looking at? Erosions in the marble from which we are to divine the traces of the crafting hand? On one level yes, it’s as simple, boring, uninspiring as that. On the other hand we are presented with the uncanny valley. The area of being where we recognise aspects of Life, described by processes that are humanist, we see expansion meaning growth, decrease meaning death, confluence meaning community, etc. We give these worlds the characteristic of a primal soul, carving crude epitaphs before facing the silence of extinction at the end of a command line.

Perhaps then automatic art, like automatic writing, conjures aspects of the viewer’s psyche that we often would rather not encounter; ashes to ashes, data to metadata.

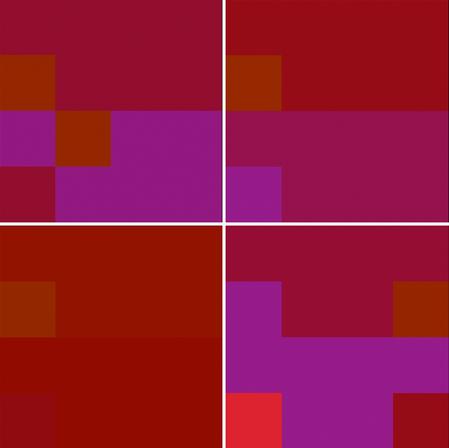

Ernest Edmonds, Four Shaped Forms (Park Hill A), 2014, acrylic and digital print on canvas, 150 x 150

Ernest Edmonds, Four Shaped Forms (Park Hill A), 2014, acrylic and digital print on canvas, 150 x 150

There are of course works that you can see in action, some of them very beautiful as forms coalesce, flower, tumesce and decay to our eyes over the course of time and algorithm. These are, however, our preoccupations and not those of the works themselves. Which is why quite often the pieces of systems art that show the end results are the most effective. They allow us to fill in the blanks outside of the process of creation.

God may be dead, but invention didn’t die with the inventor, in the end we love the concept of creation much more than the creator. Just as no one really likes magicians, but they adore learning secrets and wondering how the tricks were done, narcissistically automatic art presents us with the idea of ourselves as a template, a riddle and a positivistic philosophy.

There will be the argument about whether systems art is thoroughly the product of the latter half of last century where it began, or is composed of crystalline seeds that have started to reach maturity in our current culture. Centrist increase without ideology, information over intrinsic meaning, self defining forms born from abstract functions; whether these are negatives or positives is dependent on how your tribe weathered the last century. Surely for the post-colonial many, the manifest reality of the1960’s wasn’t easily the way things should be, regardless of high-minded intentions. Happily, one can easily see the role if not the presence of chaos in something that should be wholly determined, a meaningful space within the overt regular choices that govern each work. Area’s where self ascribed meaning (by artists or other) becomes frayed. What does it mean to encounter places where, out of context, rules turn on themselves?

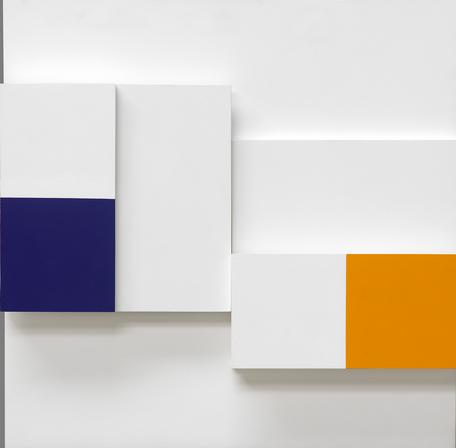

Malcolm Hughes, Relief (maquette 1), 1995, acrylic on MDF board, 50, x 50

In creating by rules the works presented show a wide variety; ranging from system-based paintings and drawings to evolving computer generated images. However, common to many of the works is the sense of complexity. High-minded blocky geometric works such as those by Ernest Edmonds and Malcolm Hughes have a grand relational aesthetic that commands a judgement from each viewer. What is simplicity when produced by process?

Looking at the work of Nathan Cohen we start thinking about how processes can be written to consider what has gone before. In essence time. Inter-related generated art has tendency not to appear as a structural whole but as a timeline of events that have an impact on each other, which gives the work a tension as, rather than a snapshot, there is a sense of timing and narrative. Whatever the outcome, we can see a history of things unfolding within the piece itself.

Nathan Cohen, Crossing, 2014, acrylic paint on board, 142 x 142

Nathan Cohen, Crossing, 2014, acrylic paint on board, 142 x 142

On a meta level the show contains this within itself as the ideas of the earlier work, which sometimes a bit more visually primitive than the later work, are carried on in later work with greater physical complexity – obviously made possible by the increases in technology itself. Tantalisingly, the viewer is challenged with each piece to look at the relationship with artist and processes as a development. An easy enough starting point, though without such easy conclusions.

Some works shown use the limitations of the replicabilities to describe human analogues and, allowing the viewer to circumscribe limited systems and make towering pronouncements on existence. The Ants in a Maze effect, similarly as Nietzsche would have it one wonders what they think looking back.

That is of course assuming that philosophical pronouncements are the focus of the viewer or reader. The creation of meaning and of why some things are important whereas others aren’t are the creative choices that make these pieces what they are.[quote]a historical overview of computation

systems, the symbolic basis

of process thought[/quote]

It interesting to think about how with generative arts ‘rules’ can mean a generative set of principles for increase/appearance/distribution rather than potentially the limitation of being (which is what we might assume ‘rules’ to mean within the human realm). The world exists without human rules, but in generative art it is through rules that the processof being begins and takes shape. Add to this the phenomenon that recognisable forms from the natural world appear in the artworks. Which in turns leads to a number of questions about aesthetic human/technology duality.

Running until the 10th of September, Automatic Art at GV Art ambitiously covers a lot of ground in its aims to present the last 50 years of artistic investigations into human and machine processes. Curated by Ernest Edmonds, who in 1969 was making art with computers using a mainframe computer owned by Leicester Polytechnic, the show brings together key pieces that exhibit a fascinating variety within the conceptual play of process-derived art.

Endlessly providing much for the imagination GV art has given us a rare chance to view a historical overview of computation systems, the symbolic basis of process thought and memetic being – a rarity where things are overwritten in our haste to rewrite our present and reassemble the dynamic materialism of our dreamed future.

Artists : Stephen Bell, boredomresearch, Dominic Boreham, Paul Brown, John Carter, Harold Cohen, Nathan Cohen, Sean Clark, Trevor Clarke, Ernest Edmonds, Julie Freeman, Anthony Hill, Malcolm Hughes, Michael Kidner, William Latham, Peter Lowe, Kenneth Martin, Terry Pope, Stephen Scrivener, Steve Sproates, Jeffrey Steele and Susan Tebby

[button link=”http://www.gvart.co.uk/#sthash.DpPKNBAk.dpuf” newwindow=”yes”] More Details[/button]

Editor, founder, fan.