[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]realise that it is difficult for me to talk in an unbiased way about the arts – I am an artist, it is an enormous part of who I am.

I have worked with many cultural organisations over the years, so I want to share just a few ways I have seen it affect not just me, but many others – both practitioners and audiences – as well as bring to light some points about its wider place in the economy.

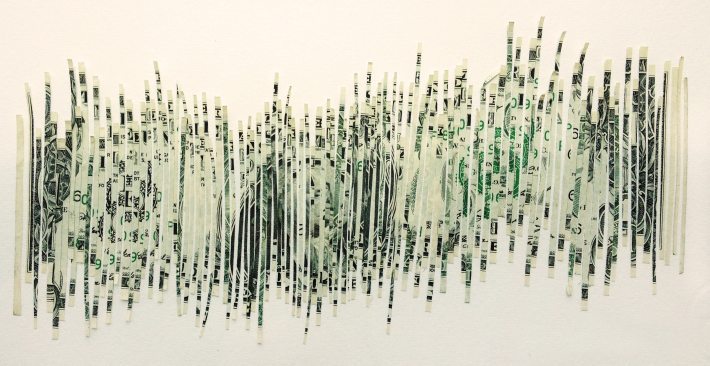

Artwork by Nicola Anthony – ‘Cash Cant bring love’, paper, dollars and collage

In a time of so many cuts in the UK, it would not be right to focus solely on the damage to the arts above other areas when we know that times are grim for many people and sectors. However, some very valid, difficult and distressing points have been made about the impact of England losing 30% of its arts council budget, and many have spoken out.

One of the worst hit areas of the cuts is Newcastle, home to the Baltic, the Theatre Royal, Dance City, the Laing Art Gallery, the Tyneside Cinema, and the Discovery Museum among others. As part of measures to save £90m over three years, Newcastle City Council has proposed 100% cuts to the arts, 50% cuts to museums and a measure to close all but two public libraries in the city.

I think it is important to truly understand how deep the arts runs within the heart of society. Even for those who think they have nothing to do with the arts, it is important to realise that its effects are all around us. The arts are ‘culture’ – the beliefs, values, development, exploration, expression and actual and manifestation of our society.

It’s who we are.

Engaging with arts and culture is a chance to become more than what we already are – on both a national level and as individuals.

Starting when I was very young, art provided me the ability to see into other peoples worlds, other cultures.

It teaches us to not exist within our own ‘bubbles’, ignorant of the thoughts, feelings, struggles and values of people around us or in far away places. Reading books, trying to invent new worlds in crayon, stumbling upon a sculpture in a park, gazing up at paintings in the awesome halls of the National gallery – in big ways and small, art opened a portal into these worlds for me and many others.

Art organisations play a crucial role in education, with their roster of events, workshops, and thought-provoking shows. But there is little money or man-power left to carry on this great work. This means that museums, for example, will mutate – from wonderful spaces for learning, discovery and contemplation, into static, musty sites that seem irrelevant to a young mind.

The arts provide the inspiration, foundation, and even education for those in fields that are fuelling Britain’s creative, information-based economy:

Architecture, graphic design, web design, the fashion industry, video gaming, writing and journalism, the film industry, the music industry, product design and innovation to name a few.

I was at a talk by Bob & Roberta Smith about the ‘value’ of arts, where the irony was mentioned that one of the leading minds at Apple, Jonathan Ive, (conceptual mind behind the iMac, MacBook, iPod, iPhone, and iPad among others), actually heralds from our funded arts scene, having graduated from St Martins College of Art (UAL).

The interesting thing about public and privately funded organisations is that many privately funded galleries, theatres and venues are being conceived of, developed and run by individuals who have spent many years developing their skills at publicly funded arts organisations.

David Lan, director of the Young Vic commented – “The theatres that get public investment are, substantively, the R and D department of the whole theatre industry – public and private – in the UK. The commercial success of the National Theatre’s War Horse in the west-end and now on Broadway enables Nick Hytner, and various commentators following him, to make a similar argument forcefully.”

Turner Prize winner Elizabeth Price, has said “If you look at my CV, just about everything I have done has come through a publicly funded institution; it is a career entirely built on that sort of support.”

In her recent article, Alison Clarke-Jenkins (regional director for Arts Council England) writes, “Playwright Lee Hall cut his teeth on theatre in Newcastle and it remains a rich source material in all its social and political complexity. His shows Billy Elliot and The Pitmen Painters are passionate versions of the value of culture and education – as at home on Broadway as on Broad Chare. And his recent open letter to the Newcastle council is as fine a piece of writing as you’ll see on the subject.”

Artists have played a part in changing the landscape and value of properties, towns and cities.

Having lived in the city for years, I have seen an organic cycle that begins in run-down areas of London when they are taken up as affordable studio spaces. Artists, resolute on creating their own opportunities, take over disused buildings to work in and curate exhibitions for themselves.

Soon, these areas become ‘trendy’ and cultured by the influence of art, property prices rise, the artists move out and the area becomes a fashionable neighbourhood for those with money to spend. Think originally of Soho, of areas now in East London, and most recently North London.

This theory has been implemented strategically in locations such as Southbank which has seen one of London’s most radical facelifts due to an injection of culture. As Boris Johnson has heartily said, “People come to London for its arts & culture. Don’t kill the goose that lays the golden egg.”

Public art schemes create a sense of community whilst revitalising and increasing the aesthetic quality of urban design. Following Liverpool’s pioneering example, many towns now have their own art biennials or festivals bringing in tourism.

Communities are grown through shared experiences.

Art has the power to do this, and the arts is the one industry that has devoted so much time, effort and care to providing these experiences – to the old and young, for people with specific access needs, the underprivileged, as well as people who need ways to connect such as ex-addicts, ex-convicts, ex-sex workers, people with psychiatric difficulties, special needs schools and young refugees, to name a few.

Art brings about inspiration and teaches us to dare to be different, to think on a tangent, and the art of thought itself.

Art is where imagination and creativity are born – two qualities that are so valuable, not just within the walls of a gallery, but also out there in the world, across all industries, sectors, and day-to-day activities.

Sadly, schools have begun marginalising art (and other arts subjects) because it is not in the core Ebacc. If we look to formative years again, we see that art expands a child’s ability to interact with the world that surrounds them, and provides new skills for self-expression and communication.

The right side of the brain is developed through art and creativity, and it cultivates important abilities that benefit a child’s development. I also know many adults who have discovered and unfolded new worlds when they found their local theatre, wandered into a sculpture park, or tried a tango class.

Culture and art – making it or experiencing it – changes lives.

At the risk of sounding like an ode to art: It holds the power to offer escape, expression or relief to those who need it. It has the alchemy needed to bring enjoyment, passion and inspiration. It enhances every aspect of our daily lives; individually or collectively, socially and psychologically.

I realise here that I am writing a kind of love-letter to culture, and as we know I am biased, I want to show you that there are also many people who indirectly engage without knowing it.

Their lives would be less enjoyable without the beauty and design visible all around them – in the clothes they wear, the architecture of the building they work in, the designed products they fill their lives with, the city skyline they gaze over – the television dramas they watch based on novels and screenplays, the film-makers who play a large part in their cinema visits, the brain-fuel from their local library as a kid, their trip with the grandchildren to the National Science museum or Portrait Gallery, the song they hum along to on the radio.

Often the reason that organisations require funding is to make their offerings free or subsidised. By offerings I mean the audience’s experience, but also, development and opportunities for the creatives – artists, actors, directors, curators.

Why is this important? Because the groups who the arts should engage with are diverse, and include the people who would otherwise not be able to experience it. This does not just mean the underprivileged, it also means youth, young adults, families, and those who do not have a cultural hub on their doorstep like some of us city-dwellers.

The arts can engage everyone. Most of all, surely, we want those who may not otherwise be able to join in, to find the world of art available and open to them – whether for simple enjoyment or for its life changing capacities.

Nicola Anthony is an artist and art writer living & working in Singapore. She seeks to discover things which make her mind crackle with creative thought. Catch @Nicola_Anthony on twitter, or her artist’s website

Nicola Anthony is a British artist known for her public art around the world. Her text sculptures are made of metal, words, memories and narratives. She has worked internationally with NGOs, art institutions, public spaces and cultural research bodies to create art which tells the stories that are often left unspoken.