Millie Chen is a London-based early-career artist working in both China and the U.K. Chen holds a BA from Nanjing Normal University, and more recently graduated with an MA in Communication and Media Studies from Kings College, London. She has exhibited her work in a number of group shows across the U.K. and has been featured as a rising talent in Bricks’ magazine spotlight on new and emerging artists.

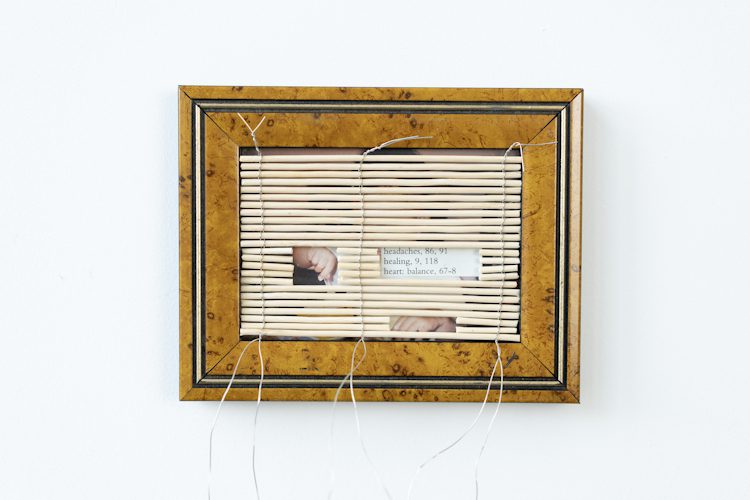

Chen works principally with found and everyday objects, reconstructing them into objects at once both familiar and slightly surreal, believing that by using these familiar artefacts of everyday life viewers will be able to better wrestle with the ideas she embeds in the works. The artist uses her works, derived principally from her own daily circumstances and life situations, to provoke and inspire conversation around the psychological tensions and traumas of 21st century life, in order to expose the joys and the anxieties many face. There are often interactive components to these works which the artist feels allows for deeper immersion into the possibilities offered by the artworks, so a door (I Tried But There’s No Door I and II, 2025) presented with a set handles offers the promise of escape, but none function, thus the door becomes a potential witness to our longing and desires which are often frustrated by both the world and the self.

Her use of mundane and everyday objects links her to a long trajectory of works which emerged through the 20th century and continues to this day, in many genres of visual art. Marcel Duchamp’s pioneering readymades arguably cemented the use of everyday objects, but the Dadaists, Surrealists, as well as other early 20th century artists such as Picasso and Kurt Schwitters and later Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, also used found and everyday objects to generate art.

While many of the early adopters of everyday objects were focused on advancing or transgressing the boundaries of art itself, Chen’s work, focused as it is on her own personal experiences with dislocation and identity, may connect on philosophical terms with more recent contemporary figures like Ai Weiwei, Theaster Gates, or Christian Marclay, who each explore themes like dislocation, identity, and trauma, as well works such as those created by Kosovan artist, Petrit Halilaj, whose artworks deal with trauma, particularly the trauma of war and social dislocation, which are informed by his childhood in a refugee camp, his family having escaped to Albania during the late 20th century Yugoslav wars.

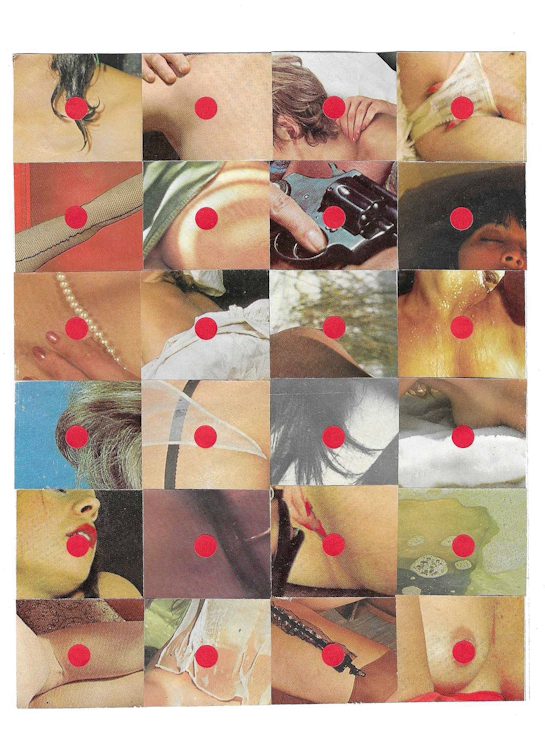

Chen’s key works thus far falls into two broad but distinct categories; mixed media which incorporate photography, text, magazines and collage, and secondly, more structural, interactive pieces, using everyday items such doors, chains, chairs and keys and other easily recognisable objects. The mixed media pieces, particularly, I Look Back and I See You (2025), and, Untitled Pleasure (2025), focus on the female body and questions of identity and memory. Untitled Pleasure, for instance, uses recontextualised pornographic images from the 1980s to challenge the hegemony of the male gaze. By reconfiguring and reframing the images Chen seeks to reclaim female agency and resist objectification.

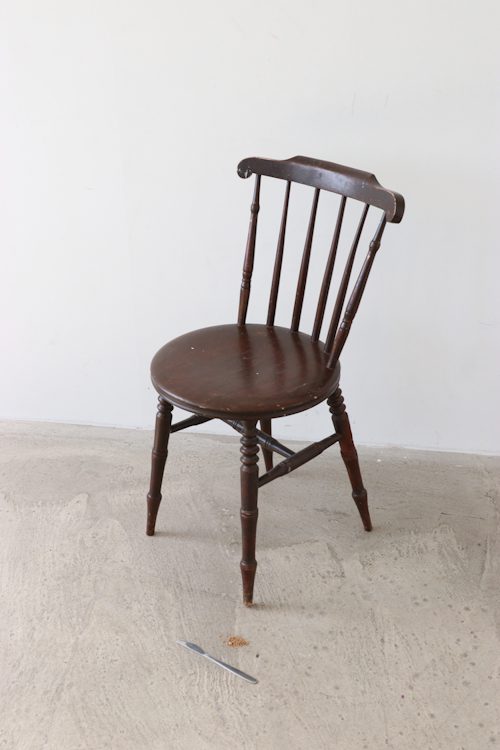

The other works she has presented are conversation generating works that invite the viewer to reflect on shared themes of diasporic identity the artist expresses through the use of daily objects with twists, which play with conventional use. A 2cm Wound, is a performance piece during which Chen cuts a wooden chair leg with a dinner knife, to explore the invisible trauma often experienced by immigrants as they navigate displacement and microaggressions. This ‘wound’ in the chair leg, created by a simple dinner knife, transfers the inner turmoil and trauma of the immigrant experience onto the chair; the small pile of wood-shavings and dust become testament to the silent wounds carried by those who are displaced around the world.

The challenge with conceptual works of any kind, but particularly with interactive pieces is whether they can truly address the artist’s intent or simply become playful distractions as someone wanders through an exhibition. Chen has a wide range of communicative skills and interests, as well as a rich vein of personal issues which resonate across boundaries, both personal and international. The challenge for her is that the conceptual doesn’t lend itself to easy interpretation. Yet her charge, as with all art, is to make the personal universal and accessible to others, and she seems up to the task.

Millie Chen Website

INKU Sphere

Images courtesy of the artist © Millie Chen

This review is part of a supported series on emerging artists including Millie Chen.

Millie Chen Exhibitions

10/2025 Group Exhibition, Autumn Salon, Candid Arts Trust, London, UK

10/2025 Group Exhibition, Rituals, Candid Arts Trust, London, UK

10/2025 Group Exhibition, Bath Open Art Prize 2025, 44AD Artspace, Bath, UK09/2025 Group Exhibition, Things Left Unsaid, FREVD Gallery, London, UK

09/2025 Group Exhibition, ESEA Sound and Performance Festival, Copeland Gallery, London,UK08/2025 Group Exhibition, Fables, Mall Galleries, London, UK

07/2025 Group Exhibition, Stay with the Murmur, Pink Gallery, Manchester, UK06/2025 Group Exhibition, Sent From…-Fringe Arts Bath, The Old Post Office, Bath, UK05/2025 Group Exhibition, 99%, Tabernacle, London, UK

03/2024 Group Exhibition, Radical Creativity-Hysteric Collective, Bermondsey Project Space, London, UK

Barry Taylor writes and speaks about the intersections of philosophy, theology and contemporary culture. In past, he was the road manager for AC/DC during the Bon Scott era before becoming a Los Angeles theologian.