How do you encourage conversations about stereotypes and prejudices without reinforcing division or controversy? The collective vocabulary may have expanded as a result of the Black Lives Matter movement, colonial legacies and structural racism are being addressed, yet Blackness is still widely considered ‘other’ in Western society.

Implicitly or unconsciously, black skin is at best exoticised or fetishised, at worst actively discriminated against and criminalised. Negative connotations run more than skin deep and are embedded in the English language, the word itself generally indicating the uncertain and treacherous, from black holes and blackouts to blacklists, blackmail and black market.

The word can be traced via Old English and its German and Norse equivalents to the Latin verb flagrare (to blaze, glow, burn) with blach describing a luminous black and swartz a dull black. The Ancient Romans also distinguished between a flat dull black which was referred to as ater, and a brilliant saturated black known as niger. As the languages evolved, the linguistic nuance based on the colour’s inherent qualities was lost. Instead, black was positioned as the opposite of white. The latter broadly associated with goodness and joy, the former with sadness and grief.

British artist Othello De’Souza-Hartley uses a stripped back palette of black hues to contextualise the implicit qualities contained in shadows and darkness in pursuit of a non-biased perception.

For a run of three weeks towards the end of 2024, a former Starbucks at the corner of Parker Street and Kingsway became a sanctuary from an overstimulation of the senses as London artist Othello De’Souza-Hartley invited visitors to enter an immersive sculpture at the heart of an exhibition intriguingly titled ‘9005’.

Surrounded by the artist’s most recent series of black paintings, the structure was conceived in collaboration with architect Laura Buechi and sound artist Elliot Buchanan. Buechi and De’Souza-Hartley’s friendship started as a meeting of two introverts hovering at the fringes of a busy party. A shared fascination with the interplay of art and architecture sparked conversations about the tensions between precision and imperfection and the balance of strength and vulnerability. Both shared deeper insights into their respective and joint practices in an artist talk hosted by architectural designer Tami Masunda.

Othello De’Souza-Hartley is a British mixed media artist based in London who investigates concepts of imperfection and its potential to create a sense of calm. Working across a broad range of disciplines, including photography, painting, performance and sculpture, he draws parallels between the textures and irregularities of human skin and the surfaces and materials defining the urban environment. A common thread through his work is the exploration of identity, the human body and its flaws. His paintings are the final stage of a meditation-led process that starts with stream-of-consciousness drawings and external triggers that may spark a specific approach. Each series is accompanied by a bespoke playlist to hold the atmosphere in the studio with an eclectic fusion of sounds that range from ambient and calm to glitchy, from minimalist to orchestral.

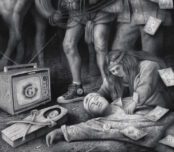

The artist’s current body of work is based on in-depth research into the different hues of Black skin tones that started with investigations of his own skin, as well as an exploration into the hierarchies of materials. Broken pieces of timber and discarded chopsticks are repurposed as structural elements, builders’ sand is mixed with inks and paint to create structured surfaces, pistachio shells are built up into bulging scars. A torn canvas thrown out by a studio neighbour forms the basis of a painting ‘healed’ with canes and layers of paint. What all have in common is the colour black.

Passersby may perceive the paintings as solid black shapes, conjuring comparisons to Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square, whose aim it was to abandon representations of reality by restricting his palette and forms. One visitor to the recent exhibition was reduced to tears as the paintings reminded them of the artist Pierre Soulages, ‘the painter of black’, known for his rhythmic explorations of the Stygian colour and its ability to transmute from non-colour to colour in relation to light. Soulage considered light itself a material and the art a presence in its own right, rather than representation.

While his are not intentional slashes but rather an intuitive response to random finds, De’Souza-Hartley’s practice can nonetheless be understood as a continuation of both Soulage and Lucio Fontana’s approach to creating art unrestricted by static definitions. A Black interpretation of Fontana’s “White Manifesto” that introduced the idea of art that incorporated colour and sound with movement, time and space – the term white in this context describing a blank slate rather than a colour.

De’Souza-Hartley’s approach to light and shadow, geometry and composition is rooted in his photographic practice. For him, shadows hold the secret to revealing the emotional qualities of a work. Applying inks and paints directly onto surfaces grants greater control over the depth and saturation which is rarely achieved in photographic prints. Unlike Anish Kapoor, who made headlines for securing exclusive rights to a light-absorbing compound, or Soulage’s use of “l’outre noir” (the ultra-black) in pursuit of complete abstraction, De’Souza-Hartley is primarily interested in exploring the effect tone and texture have on our perception and prevalent connotations of black.

Despite obvious parallels to the Arte Povera movement, De’Souza-Hartley quotes the rawness of brutalist architecture and the subtleties of Japanese aesthetics as his main cultural references. In particular the appreciation of the calm and understated qualities described by Junichiro Tanizaki in his essay ‘In Praise of Shadows’.

First published in 1933 and not translated into English until the late 1970s, the book has gained renewed popularity in recent years as a guide to a more sustainable and purposeful life in harmony with nature. Tanizaki contrasts Japanese with Western culture, in particular the former’s contentment with things as they are with dissatisfied Western progress signified by a never-ending quest for ever brighter light.

Tanizaki expanded his contemplations on everyday examples of traditional Japanese life with thoughts on the significance of skin colour and a pursuit of whiteness, describing the Japanese complexion as “white tinged by a slight cloudiness” that best suited a world of shadows. De’Souza-Hartley reverses this theory by including subtle undertones in his black paintings that are only revealed if viewed in the right light. Like Tanizaki he is aiming for aesthetic harmony through accepting things as they are, working with found materials and surfaces and incorporating flaws and imperfections. This sets him apart from Malelvich, Soulages and Fontana who based their respective theories on concepts of reduction, restriction and rejection.

Architect and collaborating artist Laura Buechi adapted Le Corbusier’s systematic approach to using colour in architecture as a means to translate De’Souza-Hartley’s ideas. The immersive sculpture at the centre of ‘9005’ (2024) turns the focus on the balance between interiority and outsideness. The smooth exterior is the only flawless surface in the exhibition. The structure’s skin is specified on the architects’ specs as ‘9005’ – the internationally recognised code for jet black – and its footprint loosely based on the outline of a human body. Panels are set at varying angles to represent aspects of diversity and individuality. The interior is designed as a safe space devoid of light to create a calm and peaceful environment, likened by one participant to a visual flotation tank. Aided by Elliot Buchanan’s nature-inspired soundscape, visitors are invited to enter a space of contrast and variance, a place where cultural constructs emerge from the darkness by context.

De’Souza-Hartley work is a study in context. His recent photographic work uses the human body to explore notions of identity and colour. Colour both related to race, gender and sexuality but also as a visual signifier in context. Approaching the essence of self by removing physical adornments and placing his, often naked, subjects amongst unrefined or everyday settings, he finds associations between human skin with its scars and flaws and the untreated rawness of modernist architecture. As he says ‘I create to explore the depth of simplicity, the beauty of imperfection, and the emotional resonance of absence’. (artist website)

With ‘9005’ he continues this pursuit of individual and universal harmony by removing the human figure and presenting abstracted narratives of the visible marks on human and manufactured surfaces alike. Led by intuition and introspection rather than intellectual theory, De’Souza-Hartley arrives at a similar aesthetic as Soulages and Fontana before him while reconnecting with the nuanced characteristics of the colour black as suggested by Tanizakis. Applied in layers of paint differing in consistency and texture, black reveals its many guises from flat and dull to saturated and luminous. Shadows of black as a material, shown in such a way as to shine.

About the Artists

https://www.othellodesouzahartley.com

https://www.instagram.com/othellodesouzahartley

Kazimir Malevich, Russia, 1879-1935

Junichiro Tanizaki, Japan, 1886-1965

Le Corbusier (Charles Édouard Jeanneret), Switzerland/France, 1887-1965

Lucio Fontana, Argentina/Italy, 1899-1968

Pierre Soulages, France, 1919-2022

Meike Brunkhorst advises and mentors Othello De’Souza-Hartley

Meike Brunkhorst is a cultural entrepreneur and freelance writer who uses her marketing communications expertise to support independent artists and cultural organisations. Her particular interests lie in international and intersectional collaborations, the amplification of underrepresented voices, and cultural practices that address environmental and ecological concerns.