Captured is a groundbreaking exhibition at Rainmaker Gallery, Bristol, in which contemporary Native American photographers shed new light on both the uses of photography and indigenous American life.

Together, the six artists represent eight different tribes and each have very distinctive styles and techniques. Their contributions consist of close-up black-and-white portraits, composite photographs woven together, sepia images so clear and detailed they look akin to etchings, compositional recreations of famous film scenes, and even a ‘talking’ tintype. This makes for an eclectic mixture of work, although the pieces are united by the artists’ desires to have Native people assert themselves as powerfully present individuals.

“Live Long and Prosper – Spock was a half-breed” by Debra Yepa-Pappan

“Live Long and Prosper – Spock was a half-breed” by Debra Yepa-Pappan

The bold and often colourful images challenge preconceived notions of American Indians conjured by popular non-Native photographers, such as Edward Curtis (1868-1952), who have fixed in time romanticised ideas about indigenous life. So by presenting work where Native people themselves hold the cameras, this exhibition provides a much-needed reassessment of photography relating to American Indians and their relationship with the photographic lens. It is particularly important for revealing that in reality, their tribal cultures are continually evolving and are no less authentic today than in the past. This is a vast project for Rainmaker Gallery to communicate in its first ever photography exhibition held in its productive twenty-five year history of exhibiting contemporary Native American art. But there is no doubt that the gallery has achieved its unique and important aims.

Specific contexts and terminologies are constantly referenced throughout the exhibition. The title clearly references the medium on show, as scenes or subject matter being ‘captured’ by a camera is a well-known phrase. Thus, the title relates to Native Americans capturing and presenting their own culture. More specifically, ‘Captured’ is a play upon the term ‘captivity narratives’, which are stories told by people imprisoned by others who they consider inferior. These stories have historically been a way for colonists to construct an inflated sense of themselves and a demeaning sense of the ‘other’. In Captured, however, Native people are given a chance to express their side of the story, their own captivity narratives, revealing that throughout history they have considered their culture to be superior to dominant white colonial powers.

In this way, the show’s title indicates a reversal of viewpoints, from outsider to insider, which is paramount to the identity of the work displayed, as well as to the ethos of Rainmaker Gallery as a whole.

The work by Chemehuevi photographer Cara Romero is the centre point. This is not only because Romero has the most work in the show, but also because of her photographic techniques, subjects and context. Romero’s photograph ‘The Last Indian Market’ is an exceptional anchor point because it portrays many famous Native American artists, the most immediately identifiable being performance art hero ‘Buffalo Man’. Thus, the piece provides a chance for these people to be portrayed by, and connected to, each other on their own terms. It illustrates a particular cultural gathering at a particular moment in time. The notion of time is certainly a dominant part of this image and one that provides both critical commentary and humour. This is highlighted by the overt references to Michelangelo’s Last Supper, apparent through the subjects’ theatrical arm gestures and postures. The cultural quotation emphasises the idea of time: Michelangelo’s iconic masterpiece illustrating a traditional subject matter and an important, pivotal moment. Romero’s photographs often reference Western and non-Native culture in this way as though to say, ‘We are watching your culture too. It is not just us that are being observed, re-interpreted or criticised’.

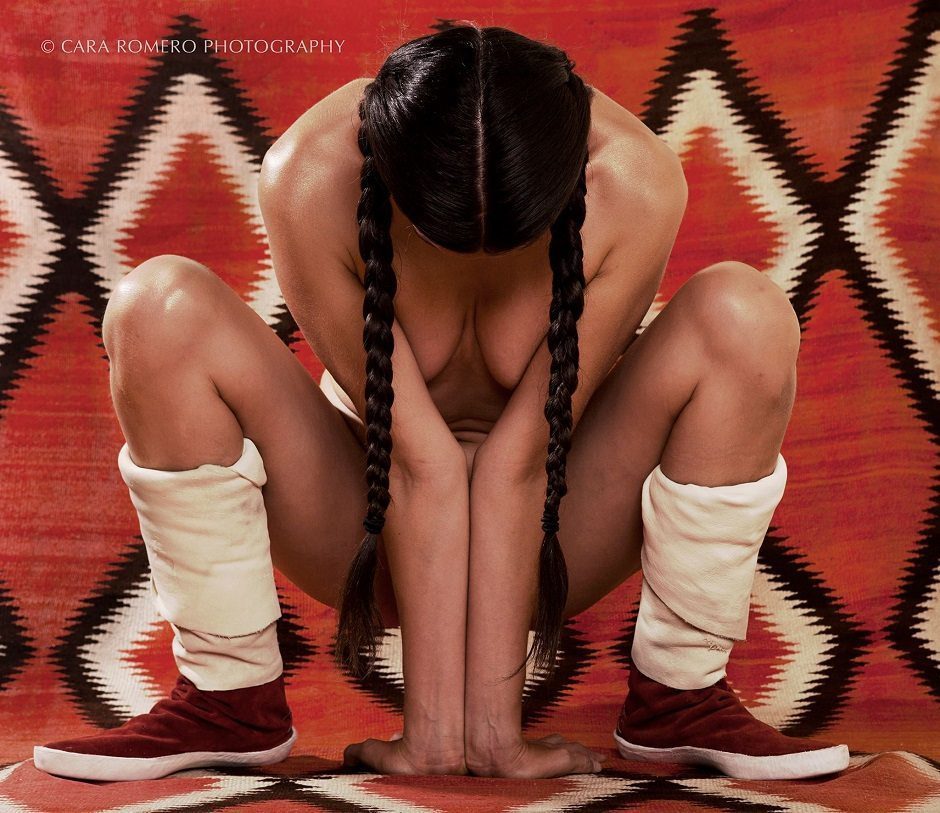

Romero asserts a definite female agenda in this exhibition with her wonderfully powerful and yet also intimate photograph ‘Nikki’.

‘Nikki’ by Cara Romero

The photograph’s modern magnifications of traditional tribal weave patterns present Native American culture through a contemporary frame, exploring current possibilities for such designs and, subsequently, the cultural practices that they symbolise and create. It is worth noting that Navajo women normally create tribal weave patterns, which suggests these women’s cultural contributions are celebrated in ‘Nikki’. The woman’s long plaited hair softly echoes these patterns, asserting her Native identityand is also an obvious symbol of womanhood and female identity. However, this is a specific Native American female identity due to not only the inclusion of traditional weave designs, but also the woman’s white and red moccasin boots, which, being the only item of clothing that Nikki wears, are highly prominent. The style and colours are suggestive of Pueblo Indian wedding boots.

Nikki’s unusual pose has multiple meanings. It references a natural pose for childbirth, a yoga pose and the idea of being in harmony with nature and touching the earth. As the pose requires physical strength, the image is also suggestive of women’s lasting fortitude. Here is a unique symbol of being grounded and in control. The pose also mirrors the diamond tribal weave behind the woman. Thus, ‘Nikki’ is a celebration of Native American women, their multiple identities and roles as wife, mother, life-giver and creative source through a contemporary lens. Nikki is not a superwoman though, but real and literally down to earth. The exposure of the vulnerable insides of her wrists suggests this, as well as indicating her great courage.

‘Nikki’ is also an assertive portrait because the woman does not make eye contact with the viewer. She reveals and conceals exactly what she pleases – and what she does reveal is not actually very much, although on a first glance we can mistakenly assume that we see most of her nude skin and are presented with a provocative portrait. However, this undoubtedly reveals more about our own culture and uncertainties, and prevents us connecting with this specific image. ‘Nikki’ is certainly a challenge to our preconceived notions of female identity and imagery. It is an invitation to open our minds and look at what is really there.

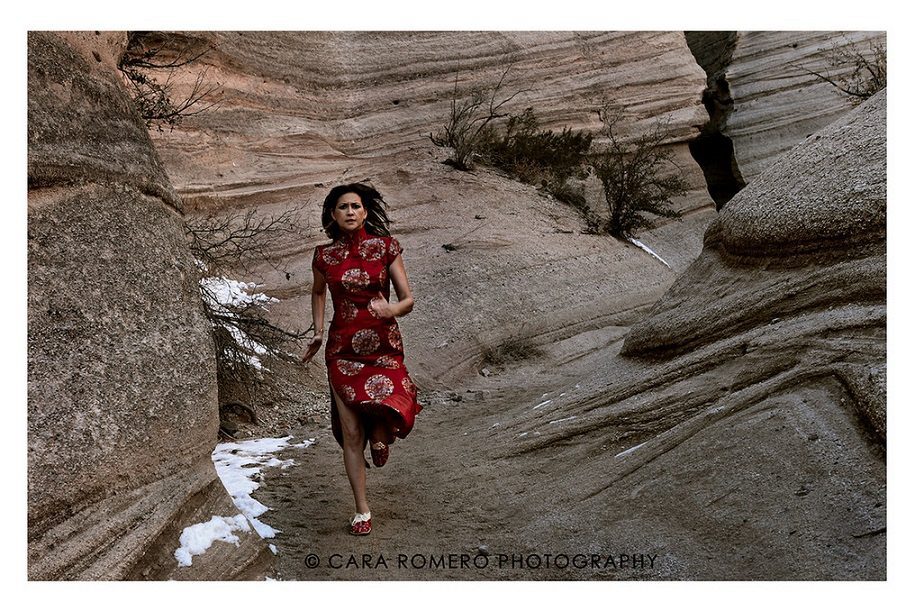

The freedom of women is also conveyed, if more subtly, in Romero’s photograph ‘A Kiss Goodbye’, which hangs near to ‘Nikki’ in Rainmaker’s exhibition. The actress and photographer Tailihn Agoyo runs towards the camera away from a dark crevice. Why does she wear a Chinese dress? When looking closely we realise she is also wearing Native American moccasins. The ease with which she can run in these shoes jars with traditional Chinese footwear, which infamously constricted and deformed thousands of women’s feet. In this way, the woman’s Chinese dress is fundamental for helping us think deeper about Native American identity and realise the positive ways that indigenous women have been treated within this culture across history.

Movement is a motif throughout Rainmaker’s exhibition, and perhaps surprisingly so because of photography’s frozen nature and ability to capture a still shot. A celebration of movement in the form of dance is evident in one of Navajo artist Will Wilson‘s tintypes, titled after the dancer it depicts, Rulan Tangen. Rulan is captured in mid dance, which is fundamental to her individual identity as a successful Native American dancer and choreographer, as well as to Native culture as a whole. This is taken further with a new enchanting twist of technology, for ‘Rulan Tangen’ is one of Wilson’s famous ‘talking’ tintypes from his ‘Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange’ project. This type of photography allows you to view not only the static image of the dance, but the dance itself by digitally encoding instructions into the photograph, which can be picked up and interpreted by a free app on Smartphones. Thus, Wilson’s talking tintypes are the result of skillfully combining nineteenth-century photographic processes with cutting-edge digital technology. They are not a way of letting go of traditions and origins, but are about making them relevant and interesting to the modern day.

There are more overt turns to tradition with Tlingit photographer Zoe Urness‘s sepia prints on woodblock. Intriguingly, she is only one photographer out of five who chooses to take this path. A controlled sense of nostalgia is communicated by the muted colour tones and subject matter of nature and ceremony. This stance is interesting considering Urness is the youngest photographer in the show. However, it is the contemporary technical brilliance that brings these themes into the present day.

Urness’s work could not be more different to that of contemporary colourists Sarah Sense and Debra Yepa-Pappan. Yepa-Pappan’s gloriously colourful depictions of her hometown Chicago celebrate her Jemez Pueblo heritage. The unusual perspectives present Chicago’s skyscrapers at odd shapes, which are humorously reminiscent of traditional Native teepees. This is an example of how she often plays with and confronts stereotypes.

Sarah Sense’s composite photographs of sunsets, landscapes and water scenes also update traditional creations. Sense combines different strips of photographs using the weave patterns of her tribe, the Chitimacha. She uses weave patterns as both distinguished shapes and as looser, fragmented forms. This suggests the dissolution of culture and craft, as well as a sense of it having an evolving journey in Native American culture. The fragmentation of the patterns also alludes to the travelling outwards from one’s origins and traditions, and subsequent merging with other cultures, identities and experiences.

Tailinh Agoyo‘s two photographic portraits of young girls Magdalena Begay (Navajo/Apache) and Macy Rose (Cherokee) point towards the present and even more so to the future. These sitters represent the budding potential of their generation as change makers and empowered activists. They are part of the artist’s evolving series ‘The Warrior Project: Indigenous Children Defend the Earth’. These portraits have a rough immediacy to them through the way they feel like spontaneous snapshots, which enhances their personal quality. With the reference to Agoyo’s ‘Warrior Project’ and the individual texts about each girl, these photographs are arguably the most politically specific and directly engaged on show.

Photography from Tailinh Agoyo‘s project, ‘The Warrior Project: Indigenous Children Defend the Earth’

Overall, Captured is a highly important exhibition where context is key. It is unique in emphasising that Native people need to be both in front of and behind the camera for giving a true taste of what authentic Native American photography (and people) can look like post Edward Curtis. Indeed, the show provides a long-overdue firsthand reflection on the nature of contemporary Native American culture. The photographic selection reminds us that there are many authentic Native voices and so not just one type of photograph that can illustrate this rich but historically troubled heritage.

Captured highlights the premise that embracing diversity is essential for the continued development of Native American art. Similarly, the show details ways in which Native people are ever changing, evolving, and equally rooted in both modernity and tradition. These notions are portrayed by thought-provoking, educational, witty and humorous means – and so, one hopes, this exhibition will speak to everyone, capturing imaginations across different cultures.

CAPTURED: A review of Rainmaker Gallery’s Native American Indian photography exhibition

5 March – 30 May 2015

For more information about Rainmaker Gallery and its exhibitions, please visit the website www.rainmakerart.co.uk, and follow them on Twitter (@rainmakerUK) and Facebook (www.facebook.com/RainmakerArt).

Helen is an independent art critic and curator with an MA in The History of Art from UCL. Her research interests include nineteenth-century French art and ephemeral objects, Rodin’s sculpture and his developments in photography, and contemporary studio craft. She also keeps a blog – helencobby.wordpress.com and a Twitter account: @HelenCobby