What do we owe the historical figures of the past? National narratives feature heroes and heroines who have guided the course of a people. Yet there are other stories too, and alternative forms of heroism. A type of prominence burns against the jingoism and moneyed patriotism associated with many historical figures—a luminescence that calls to souls not easily swayed by grand, simplistic ideas but who search for nuanced perspectives at the edges of the political. This is a place where new ideas emerge from between the cracks of repetitive behavioural cycles.

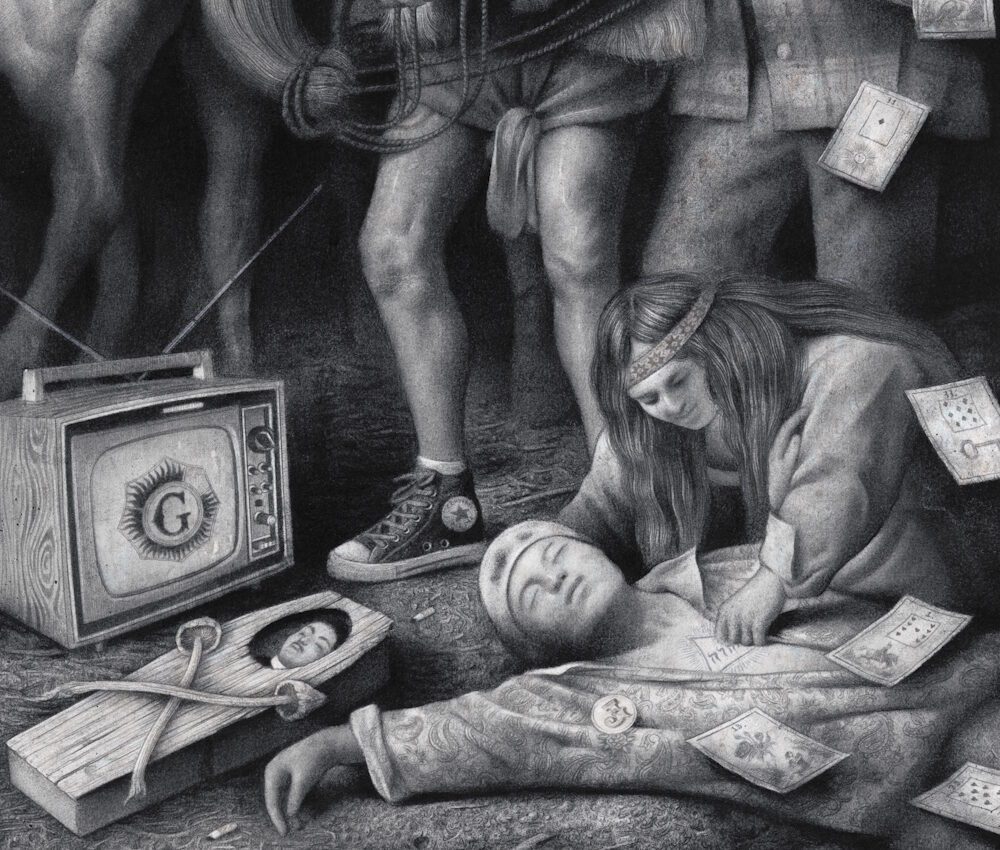

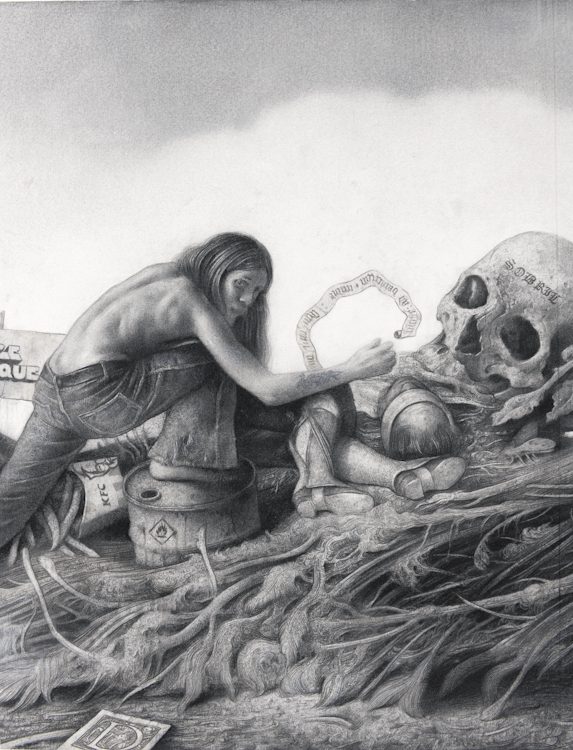

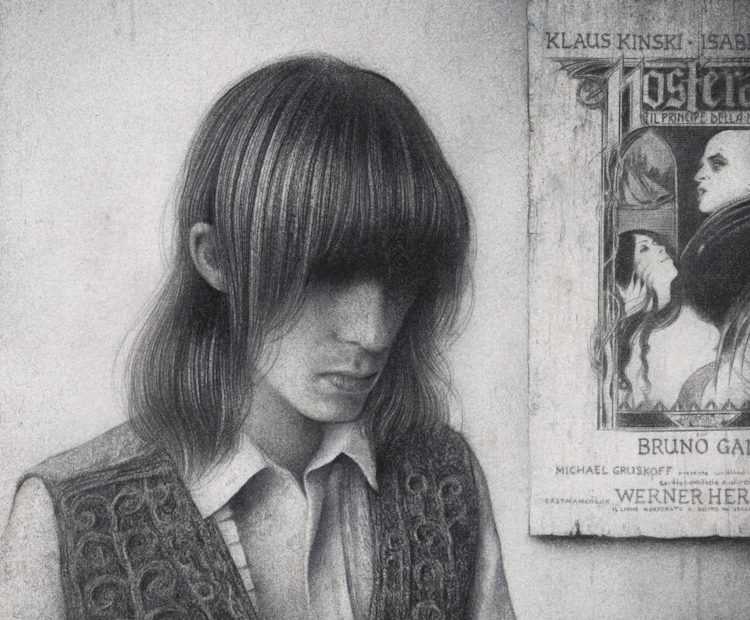

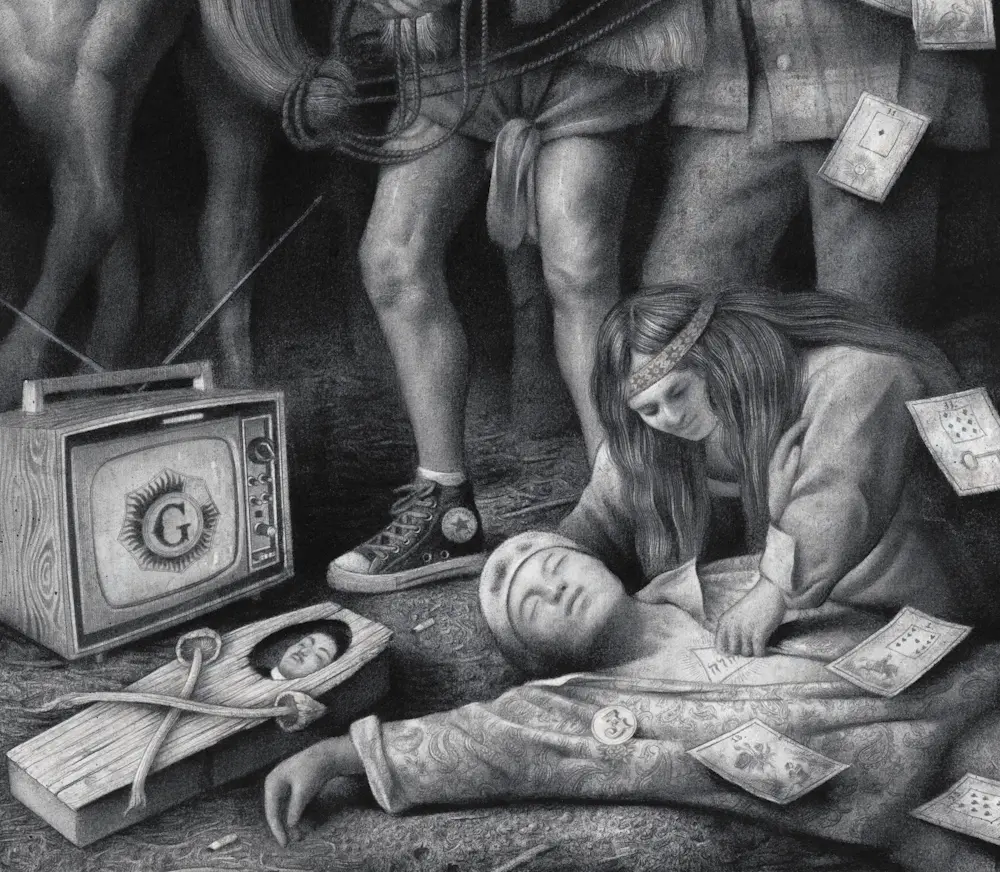

Norwegian artist Sverre Malling has explored this area of knowledge, historicity, and iconoclasm. His work presents a variety of figures, ideas, and manifestations that challenge the ordinary lexicon of common sense, venturing into areas of the unknown and uncertain. From his depictions of eccentric characters like Algernon Swinburne, Austin Osman Spare, Stephen Tennant, Genesis P-Orridge, and Shirley Collins to his latest pieces which evoke the uncanny, the cloudy world of archetype and symbol, and the darkly humorous, Malling’s practice, as much as the reductive play of symbols, concerns the layers of symbolic complexity that chart our maps and determine our onward paths.

Interviewed in late 2025 for our issue on foreign objects (Trebuchet 18: Foreign Objects), Malling answers why he portrays certain subjects in the manner he does.

What makes something foreign to you?

I think it’s mainly about belonging, or the question of the foreign becomes a question about belonging as such. The foreign, or the feeling of something foreign, emerges for me when a sense of connection is lost—something growing from a feeling of exclusion or separateness. This concerns, perhaps, my general interest in the outsider and ‘outsiderness’, as it were, which I am sure we will touch upon later. So this loss of connection I mentioned becomes synonymous with a division from the larger community. Clearly such an outside position creates, for me, interesting points of entry into—and perspectives on—the majority, while obviously involving some form of social and psychological defeat, which could potentially be disruptive, uncomfortable, and disheartening.

Yet it also signals a stand against the pressures of majority norms and guidelines for life, and there is a kind of freedom in this resistance—an opening up of new possibilities. These roads less travelled, the trails off the beaten path, can offer frameworks for engaging with the world in radically different ways; so in that sense we need the foreign in order to provide refractions and reconfigurations of ordinary, prescribed experience.

Is the idea of foreign positive or negative for you and why?

The idea of the foreign is undoubtedly positive in the sense that—to build on my last answer—it provides us with new and different worldviews, which deviate from the compliant optics of custom and habit, or rather normality. It is a reminder that the world is dynamic, ephemeral, and transitory, which I find interesting in itself. The foreign represents a valuable correction, an oblique glance.

Is all art foreign?

Well, that’s hard to say. Impossible to answer, really. I wish I had a clever aphorism or maxim to slot in here.

In your own work and the work you like do you feel you’re discovering something new? Or is it weirding the familiar? Or is it something else?

Well, for me those two become two sides of the same coin and are complementary, we could say. In an artistic context, we could say that science conquers new, unknown territory, while art rediscovers an older, inherited landscape and world. And by rediscover I mean a capacity to reshape our reading, understanding, and experience of the familiar in a wide sense. Art functions as a tool of extension, subversion, and transcendence in this regard—it stretches, purges, celebrates, echoes, and breaks with the past and the fabric of our lives. So ‘weirding’ is perhaps not really the most precise or accurate word in this connection, but it is essentially about new ways of seeing. When an artwork disrupts or disturbs my preconceptions about something, I take notice; then I am drawn in, and something happens. And here we are more or less touching the essence of what art is. I keep returning to similar points here, but all these aspects are in a way circular and contiguous.

You celebrate being positioned outside the English cultural narrative as a Norwegian. How do you balance respectful cultural engagement with maintaining that critical outsider perspective?

First and foremost, to take a larger perspective, English, or Anglo-American, cultural history has such a wide horizon and sphere of influence. It is richer and more varied than what we possess or are aware of in Norway, for instance. Our cultural DNA, I find, is much more homogeneous and uniform; it lacks the eccentricities—a good English term—idiosyncrasies, and quirks of the Anglo-cultural imagination and tradition. The latter possesses a whole expanse of what we could call social and aesthetic derailments and singularities. These are hard to identify, to pin down, and they fluctuate and permeate a more complex and convoluted cultural scene. Relatively speaking, this scene is small in Norway but enormous in England. In Norway you feel that there is occasionally a choice to make between avant-gardism and classicism, the radical or the reactionary, left-wing or right-wing, to put it simply. In England, the presence of an expansive underground, be it of a historical or contemporary kind, resists such simple dichotomies.

Historically, within the art world, English cultural history has these cul-de-sacs and dead ends which do not fit into the overall narrative, and consequently have become forgotten, overlooked, or survived in tiny cells of fandom and underground culture. Searching, like an archaeologist, in dusty corners and hidden layers of history has frequently put me into contact with these anachronistic, outmoded, and discarded figures. These individuals did not find their place within—or slot neatly into—the evolutionary development of art history. If you somehow fail to conform to the demands of the zeitgeist, or perhaps rather fail to resist or transcend the zeitgeist, you get left behind.

So I have taken a particular interest in trying to reilluminate or reintroduce some of these people, to explore whether they have a chance or a place in a different time and a different cultural climate. I actually believe that painters like Alma-Tadema and Lord Frederic Leighton could have an easier time today, certainly than during the modernism of the 20th century, in which their approach to painting was utterly anathema.

Clearly, I am also drawn to the slightly heretical position of championing this kind of art. Do they perhaps deserve a new chance and new consideration? I am not sure, but I value this line of questioning in cultural history. Unearthing or reclaiming these artists, characters, and tendencies—what were in some sense left behind—offers a plethora of surprises, gems, and inspiring histories.

You’ve drawn parallels between Norway’s colonial history and England’s marginalised figures. Do you see your work as a form of cultural solidarity between different types of exclusion?

Yes, I certainly find that my journey through the strange labyrinths of art and cultural history has fostered a sympathy with those on the outside of canonical or hegemonic narratives—careers and artistic pathways which never came to fruition or failed to conform somehow and therefore faced oblivion. So, for me it is about exploring whether there is something to be learned from these stories of outsiderness and exclusion.

In your last Trebuchet interview (2021 with Mille Walton), ‘Millie Walton speaks to Norwegian artist Sverre Malling…celebrating outsider culture’. With the rise of outsider art do you consider yourself part of the movement?

Yes. But it’s hard to label myself in any plausible way as an ‘outsider’. Because what I do and my work are obviously much closer to a stereotypical notion of art or artistic practice than what could be called ‘outsider art’ or something like that. I am by no means a boundary-breaking, avant-garde artist: what I do is in many ways aligned with traditional approaches and goes into dialogue with classical, historical, and canonical art.

An outsider, in my view, would be someone with a more subversive and critical project, one who readily and steadily attacks the consensus and frameworks of art. So whereas these artists could be described as ‘avant-garde’, my position is more commensurate with what we could call ‘retrogarde/retrograde’. And of course we can discuss whether such a position could be called ‘outsider’ today, but either way I remain drawn to what is outside the main direction of art-historical travel.

How do you see outsider art?

I am now in danger of repeating myself, but again I find outsider art productive and stimulating in that it heralds a genuinely different perspective—outsider art becomes an engine of difference as such. The world it offers us is another world, and the glimpses we’re offered can expand the settled structures of our lives. More than that, this art celebrates the very act and fact of being different. So in this sense it can help us to widen our concept of inclusivity and what’s normal. As a tool of acceptance, it can have a specific function.

You spoke about featuring utopian characters as part of your focus on that era—is that a political focus (‘rejected perspectives’) or does that come from a different place and how does that translate into your art?

It is a short distance between entertaining big dreams and expounding grand visions of the world and of art, and falling into absolute obscurity. In the history of ideas and of art, the utopian and the defunct often find themselves on intimate terms. So utopias and outsiderness cohere and intermingle in strange and different ways. I don’t really feel that my work has engaged with a lot of utopian characters, figures with great manifestos and the like, but there has certainly been a presence of individuals who potentially could have been leading lights of culture, but who ended with unresolved and unrealised careers, plans, or ideas. So I introduce the question whether things could have been different, whether cultural paradigms could have taken another direction entirely. Basically, thought experiments.

What was the most surprising discovery you made about a historical figure while researching this exhibition?

Not much of consequential significance, I would say; I liked the fact that Lord Leighton apparently had two sets of entry stairways for his models—one of which led to his studio, and one which led to his bedroom. Jokes aside, I found it fascinating reading—however apocryphal the sources—that a figure like the dandy Stephen Tennant spent enormous amounts of time in bed at his family estate of Wilsford Manor, daydreaming and fantasising about his deeds and exploits rather than doing any of them. That sort of hedonism—living a life of the imagination above all—I find fascinating in a kind of perverse way. I have no properly academic discovery to divulge, sadly.

How do you navigate the tension between your love of 19th-century illustration techniques and the need to speak to contemporary audiences?

We’re back to this idea of oppositions, that art is an occasion for embracing the paradoxical and the contradictory. This is one of the privileges of being an artist: that I get to confront and explore these binaries. In so many other—let’s call them normal—lines of work, one is forced to conform to strict boundaries of language, understanding, and expression. You work, speak, and think on terms which are not your own—this is obviously a fact for everyone, artist or not, in different contexts and roles—but in art you get to play with these rules, be polyphonic in your statements, engage in voluntary cognitive dissonance, all within the same space—and that I find highly rewarding…

Sverre Malling continues discussing his work and inspirations in part two…

Sverre Malling

At the Mistress’ Request

9 Jan – 7 Feb 2026

Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

36 Tanner Street

London, SE1 3LD

Images courtesy of the artist and KHG © Sverre Malling

Read more in Trebuchet 18: Foreign Objects

Featuring: Our Foreign Culture: Exploring Sufism and Post-Colonial Art, Outsider Stars: Sverre Malling. Dalí’s Lobster Phone And The Language Of Desire, Curves Of Thought: Simon Tayler, Bones, Helmets And Uncomfortable Truths: Victor Spinelli, The Inevitable Otherness Of Being Human, Foreign Objects In Local Places: Orobie Biennial, Europe’s Art Weeks Come Together: Spider Network, The Insecurity Collection: National Galleries, The Oracle Speaks In Silence: Ljubljana Biennale

Ex-London based reader of art and culture. LSE Masters Graduate. Arts and Culture writer since 1995 for Future Publishing, Conde Nast, Wig Magazine and Oyster. Specialist subjects include; media, philosophy, cultural aesthetics, contemporary art and French wine. When not searching for road-worn copies of eighteenth-century travelogues he can be found loitering in the inspirational uplands of art galleries throughout Europe.