[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]O[/dropcap]ne of the most influential artists from the 80s to the present day, Rachel Whiteread continues to express absence, memory and loss through casts of negative space existing within and around objects.

A unique feeling of quietness and solitude is created by the lack of life in what is represented, filling the large space with a strong unnerving presence and unconventional beauty. Shapes we can identify in our everyday lives are given authority and character; the space we move through is filled in.

The main space of the exhibition contains a large collection of Whiteread’s work, ranging from her early small-scale hot water-bottles to large life-sized library shelves and rooms. Each section of the room is very clearly conceptually divided in phases, evolving in size, colour, and objects. Her initial choice of items seems to be the most personal; the selected items often contain stronger emotional connotations. Her famous hot water-bottles appear in several colours and materials including rubber, resin, concrete, and pink dental plaster.

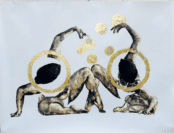

Rachel Whiteread, Untitled (Clear Torso) 1993 Courtesy of the artist

The choice of an object that serves as source of comfort and pain-relief withdrawn of its positive abilities and renamed as Torsos, ‘headless and limbless babies’, is explicitly tetric and emotionally disturbing. Ripped and folded mattresses are similarly strong in connotation: a blow up mattress is commonly connected to the lack of home or stability. Colour is used sparingly yet efficiently; a strikingly dark felt closet recalls Whiteread’s memories as a young child hiding inside of a wooden wardrobe.

As the exhibition progresses into her later work, objects become less personal and more conceptually abstract and political. The casts of the space around doors and boxes encourage the viewer to understand the role and significance of negative space whilst questioning the concept of a cast as a synonym to a copy. Her now larger and physically bolder work becomes entirely genderless and motivates inherently human questions and angsts.

Untitled (Stairs) is particularly effective in distorting the idea of positive and negative space, actively pushing the viewer to attempt to workout what the originals looked like. The negative space eating into the form of the staircase are proof of “the residue of years and years of use”, as Whiteread puts it, a concept she is recurrently interested in. None of the objects cast are perfect, but rather emphasise the flaws and deterioration created by wear. The stairs used were from her studio in East London, previously a synagogue. These indents commemorate the former residents of the space she now calls her own and acknowledges the presence of previews waves of immigration as central to the construction of London as we now know it.

Homage to history is often present in Whiteread’s work through books. Untitled (Book Corridors) features three corridors of full shelves, a solid and unchangeable monument to the past. Texts are casted with their spines facing inwards, print marks on some of the texts still visible on the plaster. Untitled (Room 101), standing at the centre of the exhibition, is a cast of the room believed to have inspired the chamber of horror in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. The original room, where Orwell himself worked, was cast in sections and the original walls removed.

However, Whiteread’s most internationally renowned works exist outside of galleries, both in remote places shying away from society and at the centre of large international cities. These large-scale commissions are present in the exhibition through photography, film, and maquettes. A beautiful real life-size resin cast of a water tank stands in the original’s tower in New York, an impenetrable concrete boathouse finds its place in Gran, Norway, and an inverted resin copy of one of Trafalgar’s plinths could be temporarily found in the famous square. My first live encounter with the artist’s work was in Vienna’s Judenplatz, where a young man proposing to a woman at the steps of Whiteread’s Holocaust Memorial drew my attention to the inverted library. The cast library shelves stand with the spines again facing inwards, in tall and impenetrable concrete. The crypt-like sculpture was commissioned by the Austrian authorities.

The film documentation of the construction and demolition of House in 1993 is striking evidence to the fact that not all of Whiteread’s public commissions were equally appreciated. The concrete cast of the inside of a Victorian terraced house in London’s East End stood in a park for 80 days before being demolished on orders from the council. The chair of the local council described it as a ‘little entertainment for the chattering classes of Hampstead’. The sculpture awarded her with both the Turner Prize for best young British artist as well as the K Foundation award for worst British artist in 1993. The video of its construction and destruction on loop is a work of art in itself.

A vitrine holding a collection of objects found in Whiteread’s studio gives the viewer access to the inner-workings of her mind. Small sketchbooks with lists of words and objects she gives importance to, an array of mixed items such as spoons of different sizes and consistencies show us the inspiration she draws from small and seemingly insignificant materials. Every object is individually selected and studied.

Rachel Whiteread’s largest exhibition at the Tate Britain three decades into her career gives the viewer a comprehensive understanding of her work, both in physical form as well as recordings. The immense space allows for further insight into her entire working process, including the initial brainstorming and planning. Not only was Whiteread the first woman to win the Turner Prize 1993 and represent Britain at the 1997 Venice Biennale, but has manage to maintain her status as a relevant and influential artist through the space of three decades.

Until 21 January 2018 at Tate Britain, Millbank, London

Born in Barcelona and based in London, Anna writes about art, techno and psychogeography. She is also a lover of film photography and is slowly building an Olympus camera collection.