[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]M[/dropcap]ovie Scores are at an all-time low.

I am not referring to the precious Nielsen ratings by which Directors and Producers have their product pre-rated by test audiences.

I am talking about the lost arts of movie music; skills such as the creation of stirring title themes the audience will remember for a lifetime, developing recurring, yet never quite repeating, motifs to assist the progression of character or the precise ability to underscore dialogue with a light and delicate touch.

Hans Zimmer and his factory of Zimmer clones put an end to all that long ago. Original movie music today is mostly just wall-to-wall glue for cracks in the film.

Some truly great movie scores?

Planet of the Apes (original) by Jerry Goldsmith

The Magnificent Seven by Elmer Bernstein

The Shawshank Redemption by Thomas Newman

Lawrence of Arabia by Maurice Jarre

Star Wars by John Williams

Rosemary’s Baby by Krzysztof Komeda

Psycho by Bernard Herman

The Mission by Ennio Morricone

Blade Runner by Vangelis

Back in the day even less than memorable films were often blessed with spine tingling music. Quentin Tarantino (a great student of these matters) rescued the ‘whistling theme’ by Herman from a so-so British thriller Twisted Nerve and transplanted it into the corpus of Kill Bill to great effect.

[quote]the shower scene in Psycho would not require a music cue[/quote]

Old-school composers mostly emerged from a concert hall or jazz background. They were respected, if not always liked, by filmmakers as they brought both a finely tuned ear for drama and the stink of high art to the process. Hitchcock blithely informed Herman that the shower scene in Psycho would not require a music cue as it would play better off the sound effects.

Fortunately the stubborn and arrogant composer ignored ‘his master’s voice’ and produced a brilliant movie moment which the Master of Suspense was never slow to take the credit for.

On Spielberg’s Jaws the relatively inexperienced director asked John Williams for rippling harp arpeggios (a pirate movie cliché) to delineate the shark. Williams, ever the populist, responded by creating the much-copied and daringly simple Jaws Theme – ominous and disturbing even on shots of open water under a clear blue sky.

It has been reported that Ridley Scott disliked the score for Blade Runner and blamed it for the poor reception to the initial release of the film. Even now, when the picture is considered to be an all-time classic, Ridley is less than fulsome in his praise of Vangelis’s outstanding contribution to the movie.

You could, and I will, say that the sharp decline in quality of original movie music began with Ridley Scott’s replacement of Goldsmith’s sweeping and unashamedly romantic orchestral score for the 1986 film Legend in favour of electronic ‘ambient’ music by Tangerine Dream. Despite wonderfully art-designed sets and the presence of a young Tom Cruise the film tested badly with its target audience of young filmgoers. Probably because the fragile fairytale was spun with lead rather than silver, however, once again, the music was blamed.

After consultation with his now deceased brother Tony (who had recently had great success with a Eurocentric electronic score on his Beverly Hills Cop movie) T Dream were brought in to revitalise the project for the American market.

To no avail

The film still tanked worldwide. The great composer, who had never in a long and Oscar-winning career worked as hard or as long to create a masterpiece, at least had the satisfaction that his original score was preserved for the European release. This gives the film the curious distinction of being, to my knowledge, the only chance for students of the medium to compare two completely different approaches to the same problem: how to breathe life into a dead turkey.

The Goldsmith version wins hands down. Its musical quality and attention to dramatic effect gift a dreamlike quality to the heavy handed narrative, whereas T Dream’s music serves to foreshadow the contemporary approach to scoring: either the music loiters too long without much intent, making only vague gestures in the direction of the drama like a sulky teenager forced to sit at the family dinner table, or simply hammers away like the clap of doom throughout confusingly shot action sequences.

version wins hands down. Its musical quality and attention to dramatic effect gift a dreamlike quality to the heavy handed narrative, whereas T Dream’s music serves to foreshadow the contemporary approach to scoring: either the music loiters too long without much intent, making only vague gestures in the direction of the drama like a sulky teenager forced to sit at the family dinner table, or simply hammers away like the clap of doom throughout confusingly shot action sequences.

I like T Dream but don’t consider that they were ready, at that time, to handle either the dramatic requirements or political struggles that accompany a picture of this scale.

Legend’s failure to succeed with either a ‘teen friendly’ or a ‘classical’ score should have taught Hollywood a sharp lesson. Unfortunately nothing was learned from the experience. Coinciding with a surge in the sales of soundtrack albums featuring pop songs, the next three decades would see an increasing amount of composers blamed for a film’s failure to test well; more last-minute score rejections and composer replacement; the increased use of ‘temporary’ tracks (any old music by anybody at all) for test screenings; a veritable witch hunt of ‘difficult’ European composers such as Morricone/Vangelis/Yared and the rise of the character-light new school including James Horner, Hans Zimmer and Harry Gregson Williams.

After a brief intermission (refreshments are available in the foyer) I will return to the blame game and continue to point accusing fingers for your informational entertainment.

TO BE CONTINUED

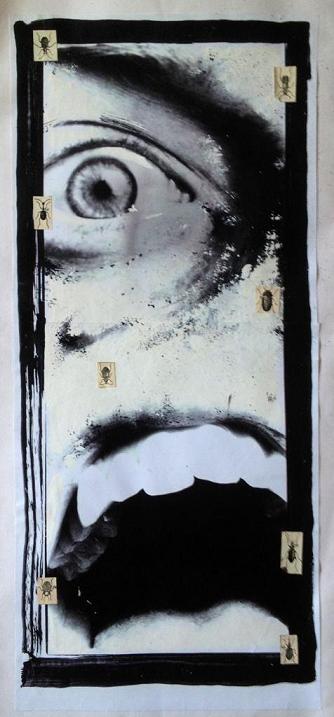

Illustration by Dan Booth

Having completed principal photography on phase one of the Sharks revival SWP is now preparing to edit the One Last Thrill feature documentary. Sharks themselves are ‘dropping a big one’ by releasing a double album Dark Beatles/White Temptations in April 2018.

In his spare time the author kayaks the muddy river Ouse and walks the South Downs which gently enfold his home town of Lewes.