David Lynch died unexpectedly while preparing a major exhibition at the DOX Contemporary Art Center in Prague. Diagnosed with emphysema in 2020, and fearful of the damage Covid could add to his lungs, he told a reporter, “I can’t go out… I can only walk a short distance [across a room] before I’m out of oxygen” (Wigley 2024). Nevertheless he had to evacuate his home when fire spread across the Hollywood Hills on 8 January 2025. His health was affected and a week later he died.

At first it looked like the Prague show might be cancelled, but in the end it was just delayed. It opened on 19 June 2025, and runs until 8 February 2026. Nearly 400 works on paper by Lynch – photographs, lithographs, drawings and watercolours – plus a tight selection of short videos, experimental films and animations, fill 9 rooms and 3 projection halls, with a selection of his feature films (and films he cited as influences) shown outdoors on DOX’s grass-covered roof once a week throughout the summer.

Although best known as a filmmaker, Lynch saw himself as an artist not confined to any one medium. He was a conjurer of moods and places, a creator of dream worlds inhabited by strange, troubled, charismatic characters who were (as the actress Patricia Arquette put it) “close enough to our own [world] to be really disturbing” (Keeler 1997).

“Ideas are the number one best thing going,” Lynch often said in interviews, and he was happiest when “falling in love with an idea” and figuring out how to translate it into physical form. Some ideas were best suited to cinema, others were realised as graphics, still others became furniture, tie clips, incense burners, ceramics, soundscapes, songs or music videos. “David exists in an art bubble he created himself, and he’s rampantly creative,” his friend, the Polish composer Marek Zebrowski, says (Lynch & McKenna 2018, p. 452). He was a problem solver gifted with a rare combination of a wildly roaming imagination and the skills and discipline needed to manage large teams tackling complex tasks. By all accounts he was a workaholic, fuelled by caffeine and nicotine.

“Lynch’s idea of relaxing is to make something,” noted his biographer, Kristine McKenna.

“Childhood experiences can shape you,” Lynch explained, “and my childhood years in Boise [Idaho] were hugely important to me… my dad always had a woodshop. He was a craftsman and he rebuilt people’s musical instruments and made ten or eleven violins… I always loved making things, and the first things I made were wooden guns… I’d carve them and cut them with saws and they were pretty crude. I loved to draw, too…” (Lynch & McKenna 2018).

In 1961 he learned that one of his friends’ father was an artist: Bushnell Keeler. That planted the seed in David’s mind of becoming an artist and it never left him. Keeler made space in his studio so David could paint there, and eventually rented him a room in his house so David could have his own studio. The Lynches had moved to Alexandria, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, DC, so David started attending painting classes at the Corcoran School of Art while he was in high school. Even though he could already produce reasonably accurate representations of people and buildings, he began to rebel against the Corcoran’s tacit assumption that the main goal in making art was to demonstrate skill:

“David got into painting darker things,” his friend Jack Fisk recalled. “Docks at night, animals dying—real moody stuff. David’s always had a cheerful disposition and sunny personality, but he’s always been attracted to dark things. That’s one of the mysteries of David” (Lynch & McKenna 2018).

Fisk offered this anecdote in another interview:

“One day he brought in a painting that was of a dock with greens and blacks and it was just thick with oil. He was showing it to me and was pretty excited about it, and then this moth flew into the painting and it got stuck in the thick oil paint and started like flapping around and made this big spiral and that was the death of this moth. I was thinking that he would take it off and repaint it, but he fell in love with it. He said ‘This is great!’ And so from that day on, he started putting little bugs and stuff in his paintings…” (Keeler 1997).

According to Peter Deming (director of photography on many Lynch projects), “David is the kind of person who kind of relishes in mistakes… he’ll use those and go even farther…” (Keeler 1997). So it’s not surprising that his paintings and graphics are full of what other people are likely to perceive as errors and accidents – scrawled words that are almost illegible, scribbled telephone numbers, unbalanced compositions and a general disregard for rules and standards – unlike the painstaking craftsmanship he displays when making furniture, films or photomontages.

His openness to accidents and errors comes from recognising that some things happen for a reason even if we don’t know why. Not knowing why is actually a normal life experience, a feature not a bug. Isabella Rossellini, who starred in Blue Velvet, remembered that “He once said something that really helped me understand his work. He said, ‘In life you don’t know everything'” (Lynch & McKenna 2018). Many of the works shown at DOX have large areas of black because that colour, according to Lynch, is the “darkness of the unknown”:

“Colour to me is too real. It’s limiting… The more you throw black into a colour, the more dreamy it gets… Black has depth. It’s like a little egress; you can go into it, and because it keeps on continuing to be dark, the mind kicks in, and a lot of things that are going on in there become manifest. And you start seeing what you’re afraid of. You start seeing what you love, and it becomes like a dream” (Rodley 1997, p. 20).

Lynch is a master at exploiting that feeling of not knowing why something happens as a source of tension, mystery and engagement:

“To me a mystery is like a magnet. Whenever there is something that’s unknown, it has a pull to it. When you only see a part, it’s even stronger than when you see the whole… I think fragments of things are pretty interesting. You can dream the rest. Then you are a participant” (Rodley 1997, p. 26).

In 1964 Lynch matriculated to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, but quit after a year. “I was not inspired AT ALL in that place. In fact, it was tearing me down, because I had such high hopes. So off we went to Europe” (Rodley 1997, p. 33). He planned to spend a few years abroad studying art but, disenchanted, flew back to Virginia after only two weeks: Europe “felt like way more of the last century” (Rodley 1997, p. 33).

After a series of boring low-paid jobs, he decided to join his friend Jack Fisk who was studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art in Philadelphia. A class assignment to “make a painting that moves” led him into film making:

“The core event of the David Lynch creation myth took place early in 1967. While working on a painting depicting a figure standing among foliage rendered in dark shades of green, he sensed what he’s described as ‘a little wind’ and saw a flicker of movement in the painting. Like a gift bestowed on him from the ether, the idea of a moving painting clicked into focus in his mind… he rented a camera from Photorama, in downtown Philadelphia, and made Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times), a one-minute animation that repeats six times and is projected onto a unique six-by-ten-foot sculpted screen. Made on a budget of two hundred dollars and shot in an empty room in a hotel owned by the Academy, the film pairs three detailed faces cast in plaster, then fibreglass… with three projected faces… The bodies of all six figures in the piece have minimal articulation and centre on swollen red orbs representing stomachs. The animated stomachs fill with coloured liquid that rises until the faces erupt with sprays of white paint that trickle down a purple field. The sound of a siren wails throughout the film, the word “sick” flashes across the screen, and hands wave in distress” (Lynch & McKenna 2018, p. 67).

A classmate impressed by Six Men Getting Sick commissioned Lynch to make another film, which became The Alphabet (1968), a 4-minute “nightmare about the fear connected with learning,” as Lynch described it (Lynch & McKenna 2018, p. 68) (he always did poorly in school).

Bushnell Keeler then encouraged him to apply for an American Film Institute grant. His application included The Alphabet and a script he had just written for a film to be called The Grandmother. He got the grant, and the stylistic traits that would make his later films so distinctive made their debut in The Grandmother:

“First, we enter a house, or a house garden, where parents crawl on all fours, their faces twisted in grotesque masks. When they speak, they don’t use words. They bark and growl like feral animals… And the sound, too, is unlike anything you’ve heard before, because Lynch and his sound designer, Alan Splet, literally created it from scratch. They’d spend hours recording and manipulating everyday objects: the squish of wet newspaper became the sound of soil. The scraping of metal was transformed into inhuman parental screams. The visuals are equally revolutionary. Lynch, still thinking like a painter, shoots in stark black and white until moments of pure emotion burst onto the screen in explosive colour. Watch closely as the boy’s bedroom transforms into a dark void where the only sound is the soft patter of soil falling through his fingers as he plants the mysterious seed. He literally soils his bed using a bucket to grow a life… Then comes the moment that changed experimental cinema: the grandmother’s birth. From the soil erupts a mass of pulsing organic matter transforming into an elderly woman in a Victorian dress… Lynch films her emergence using a mix of stop-motion animation and live action, creating a sequence that feels both primitive and otherworldly. The grandmother never speaks but the sound design tells us everything: a gentle hum that cuts through the parents’ animal noises like a lullaby through a nightmare.

“Looking at Lynch’s later masterpieces, you can trace everything back to this student film: the red curtains and pulsing sound design that would later define Twin Peaks; the body horror and industrial soundscape that would evolve into Eraserhead; the contrast between domestic normalcy and underlying horror that makes Blue Velvet so disturbing; and even the crackling electricity and flickering lights that would become Lynch’s signature. This wasn’t just a student experimenting. It was an artist discovering his voice” (Vakrokti 2025).

Six Men Getting Sick, The Alphabet and The Grandmother are all in the DOX exhibition, along with several other short films. Their presence makes questions about his films’ relationship to his graphic art unavoidable, especially since Lynch’s film making began as an offshoot of painting and he continued producing static image artworks prolifically to the end of his life, even during breaks between scenes when shooting films. What the DOX show makes clear is that Lynch worked in different media for different reasons. Different skill sets were required, producing different making experiences; and different kinds of content were favoured by different media with differing measures of success. Looking for similarities across media is thus missing the point: the differences are what mattered.

Lynch publicly exhibited his paintings and pastels sporadically in the 1980s, then regularly in the 1990s. His career as a visual artist took up the slack from a series of disappointments in film. According to Kristine McKenna, “Lynch began turning inward” after the Twin Peaks prequel, Fire Walk with Me, was booed at Cannes and proved weak at the box office. Then contract disputes arose with some of his production backers and he failed to fund his script to film Kafka’s Metamorphosis. “During those years David painted nonstop, he got a kiln and was doing pottery for a while, and he designed and built furniture in his shop. He did lots of photography and had several exhibitions,” according to Mary Sweeney, a long-time collaborator who he eventually married (Lynch & McKenna 2018, p. 312).

A retrospective at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris in 2007 was a significant milestone. It produced an extensive catalogue and the show travelled to Milan, Moscow and Copenhagen. Organized by Hervé Chandès, it was titled The Air is on Fire: 40 Years of Paintings, Photographs, Drawings, Experimental Films and Sound Creations by David Lynch. That exhibition indirectly supplied the opening DOX would use to contact Lynch.

“The Air is on Fire was the first time I was able to see a lot of my work together, and that was a beautiful thing. It’s always been the case that if you do one thing you’re not supposed to do other things – like, if you’re known as a filmmaker and you also paint, then your painting is seen as kind of a hobby, like golfing. You’re a celebrity painter and that’s just the way it was. But around the time I had that exhibition, the world started changing, and now people can do anything. It’s way, way good, and that show put me on the map. I have Hervé Chandès to thank, big time… I got so many offers for shows after The Air is on Fire, and it inspired me” (Lynch & McKenna 2018, p. 462).

While Lynch was in Paris for the Cartier show’s installation, Chandès suggested that they visit “a place you might love”: a skylit workshop owned by Patrice Forest, with huge 19th century presses that had printed lithographs by Picasso, Miró, Giacometti and other well-known artists. Lynch was enchanted. Forest asked David if he ever made a lithograph, “and he said, ‘Never…’ and he went to work immediately… Since that time we’ve made more than two hundred lithos, and when he comes to Paris he has as much time in the studio as he wants” (Lynch & McKenna 2018, p. 444).

DOX’s chief curator, Otto M. Urban, picks up the thread:

“The particular idea to exhibit David Lynch’s artwork [in Prague] first appeared in 2010 when I was preparing the exhibition Decadence Now for the Rudolfinum Gallery. I wanted to include some of his work in that exhibition and unfortunately that didn’t happen… We addressed the various galleries that represented Lynch and they either didn’t respond at all or they responded negatively. Given that I know a bit about the art milieu, it was clear to me that the information never reached Mr. Lynch. So we also sought some personal contacts in various contexts and those never came through – until we were preparing the exhibition Kafkaesque [at DOX], where we also counted on Lynch’s work from the beginning. Actually, for me, Lynch, or his artwork, was the first inspiration for the exhibition Kafkaesque.

“And then we found that lithography studio and gallery in Paris… Item Editions. They had been working with Lynch for a long time, so we approached them to see if they would lend us some lithographs. They very readily agreed and the collaboration with them was very pleasant, so I visited the studio in Paris to personally thank Patrice Forest… Their workshop is remarkable. There are very old printing presses on which the great artists of the world printed and on that occasion I told him about my idea, about my dream [of showing Lynch’s artwork in Prague]… He said he liked the idea, and he liked the Kafkaesque exhibition’s catalogue very much. So he promised that he would approach Lynch and tell him the idea. Before I left, he took a picture of me at this big lithographic machine called Moby Dick, where he also printed Lynch’s work, and he promised to send him the photo…

“And within a week I heard from Michael Barile, who is – or was – Lynch’s personal assistant. We started talking about how big the exhibition could be, what it would contain, and so on and so forth. And what followed was actually a period of three-quarters of a year where we were in contact with either the studio or Lynch… We exchanged concepts of the exhibition and when it got to some nearly final shape, I expressed an interest in presenting the project in person… That was quite exceptional. Michael Barile said that they actually turn down 99% of all requests. But in this case, he liked the setting very much. Lynch was interested in Prague. He was interested in DOX. He liked the Gulliver [a large wooden dirigible suspended above DOX, used mainly for presenting literary events], so he agreed to meet…

“Contracts for the loans and transport of the work were about to be signed the week that Lynch died. Everything was set up because the show was originally supposed to start on the 3rd of April. Michael Barile remembers that the day before Lynch died they were watching movies together. They talked about the DOX show and there was no indication that the following day David Lynch would no longer be alive. So even his studio was paralysed. They didn’t know what was going to happen. And the fact that they started having to deal with estate stuff, inheritance proceedings and a whole bunch of other issues led to the fact that going forward with the show was suddenly at risk. Understandably. But Michael Barile and Anna Skarbek from the Lynch studio both knew that he wanted the show, so they saw it as their duty to get the thing done. It was going to be the first major Lynch exhibition this year in Europe, which was also important, and it would be hard to cancel at the last moment without compensation.

“So despite the adverse circumstances, the fact that he was involved in the planning and had already agreed to it was a very important argument for us to actually complete the project” (Urban 2025).

Lynch had developed a strong connection to Prague, visiting the city to work on soundtracks for his films with composer Angelo Badalamenti, starting in 1986. “The mood of the people, the buildings, and the deep quiet were the perfect environment to record music for Blue Velvet, and David loved it” (Lynch & McKenna 2018, p. 219). Music for Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive was also written and recorded in Prague.

The DOX show’s title – Up in Flames – comes from a song Badalamenti wrote for the film Wild at Heart. It acquired uncanny relevance when fire engulfed Lynch’s Hollywood Hills neighbourhood. There was some concern that this tragedy could change the way the exhibition’s title would be understood, but Lynch had approved it months earlier and fire is in fact a recurring theme in his work so the title was not changed.

There are 378 artworks in the show, not including the films mentioned above: 144 photographs, 82 lithographs, 77 drawings, 50 aquarelles, 12 woodblock prints and 13 uncategorised works on paper. Most were made in series that the exhibition keeps together and presents in neat rows and clusters. Because Lynch hated the sterility of white gallery walls, his rooms are painted dark grey, light grey, amber orange and bright red. (The red they picked is actually marketed as “Twin Peaks Red” because it matches the TV series’ Red Room.)

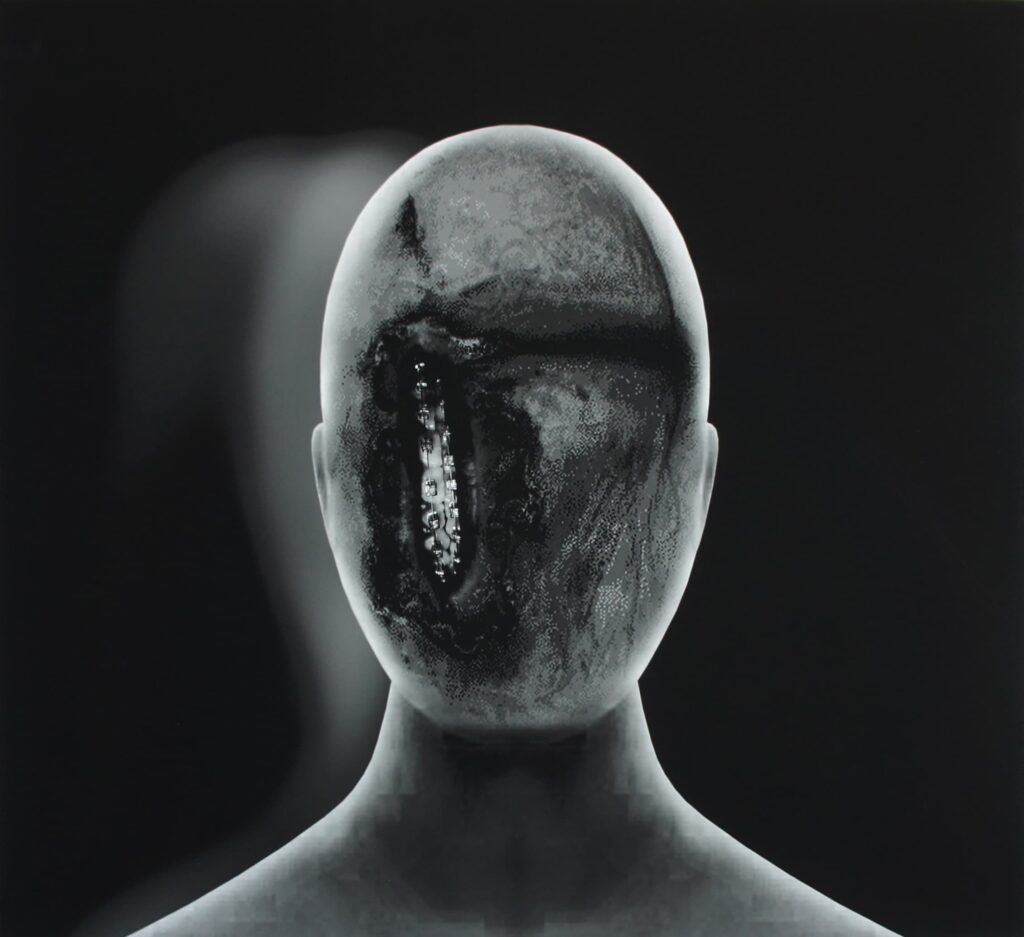

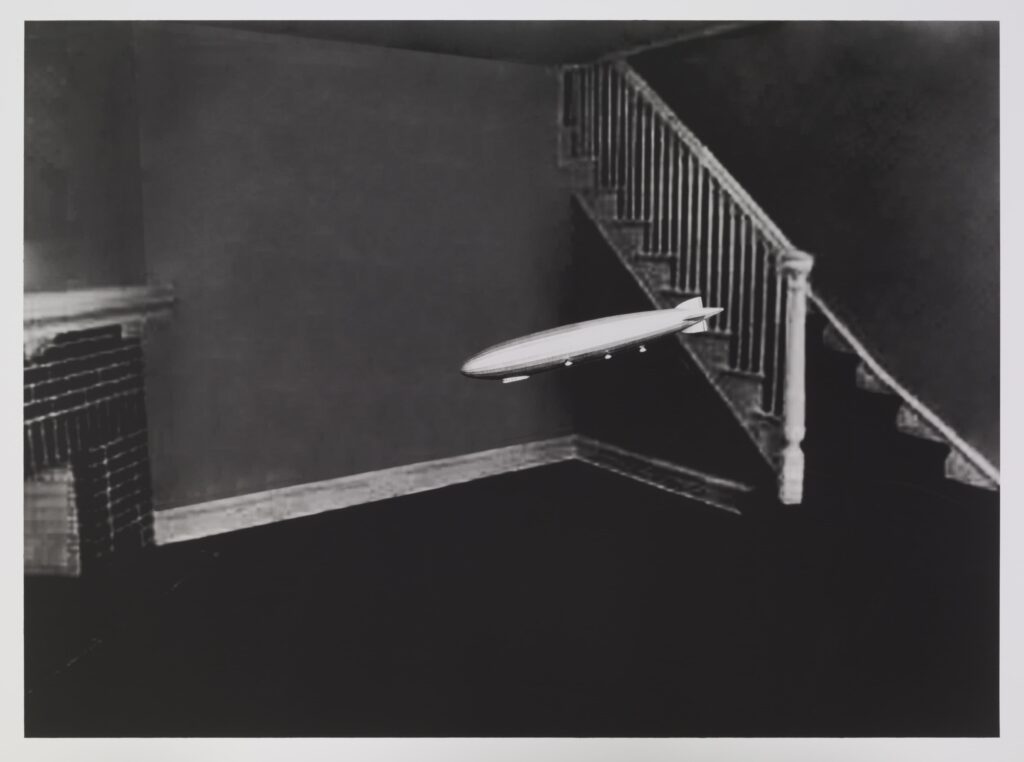

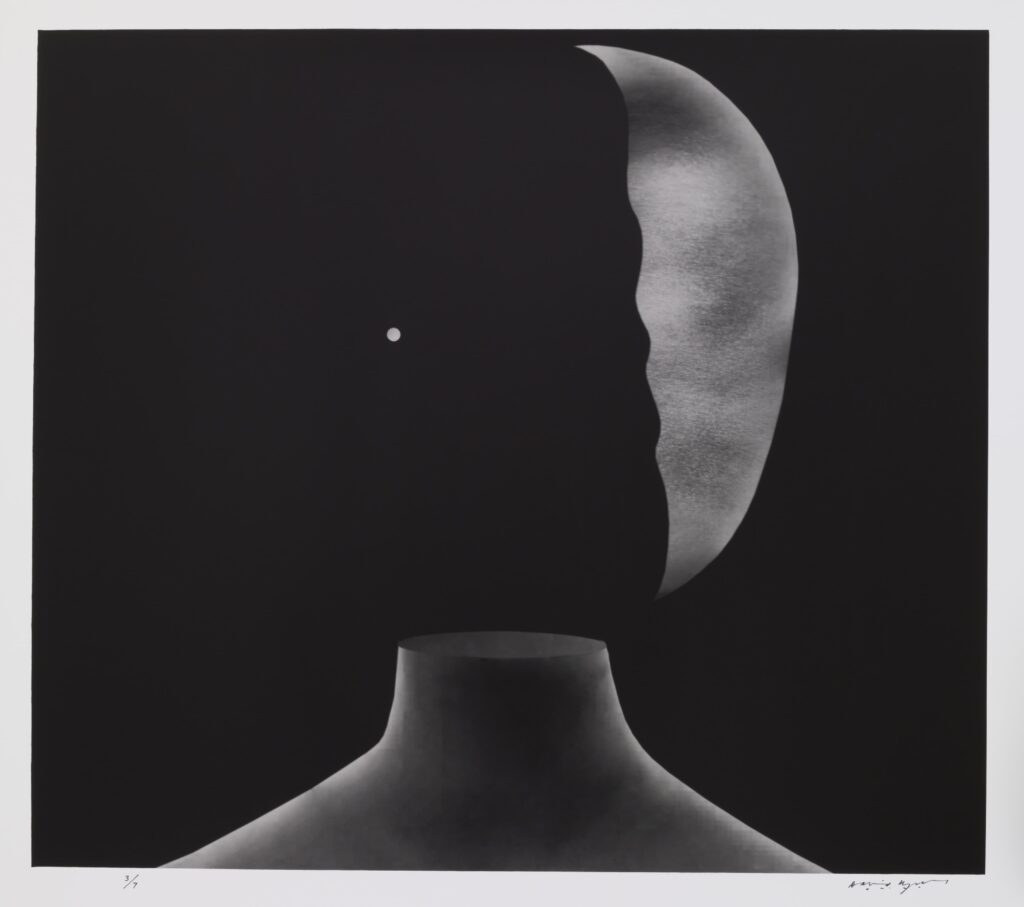

The biggest series of photos is called Small Stories, which contains several different sub-series: fifteen large Heads confront visitors as they enter the exhibition. These were made by photoshopping diverse images into the same silhouette as if they were facial features (an example is shown above). They look like monstrous mannequins or book cover illustrations for a sci-fi novel. The other sub-series – Interiors, Windows, Dreams and one-offs with individual titles – would take too long to describe but they are probably the highlight of the show, showcasing Lynch’s ability to suggest stories by combining images in enigmatic relationships. The fact that they are static actually increases their impact.

Another large series of photos shows “derelict” factories in New York, New Jersey, Berlin, Łódź (Poland) and elsewhere. These may have started as a site selection tool for scenes to evoke “Victorian London” in The Elephant Man. But Lynch continued to seek out and photograph such places long after he had any practical reason to do so: he simply liked scenes of industrial decay. Harsh interplays of natural light and shadow dominate these monochrome pictures. Their formal strength and “lens love” save them from being merely sad.

That dynamic is not at work in his snapshots of snowmen on the front lawns of houses, unfortunately. Those are merely sad. On the other hand, Fish Kit and Chicken Kit are genuinely funny parodies of educational kits for children. Lynch bought a mackerel and a chicken, cut them up and mounted the pieces on sheets of cardboard. Each part of the animal was labelled with instructions like “Fish tail – add to body” and finally, “Put fish in water.” The boards were created to be photographed as the originals rotted quickly.

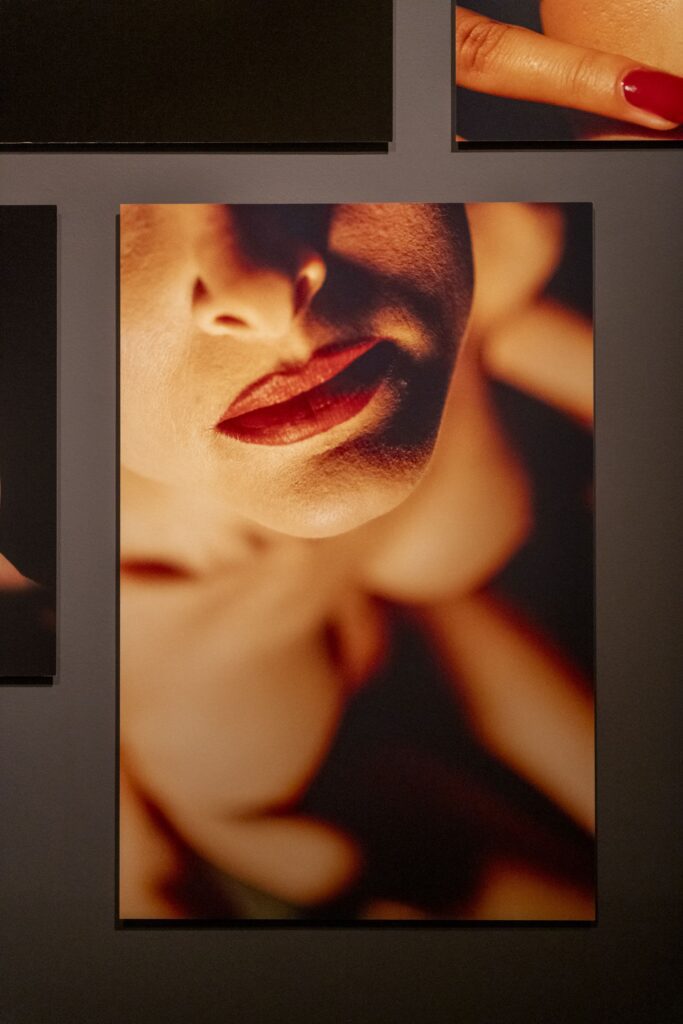

Yet another large group of photos consists of Distorted Nudes. These were photoshopped to approximate the darkroom montage techniques of earlier decades. Lynch has always been fascinated by deformations of the human body. This collection ranges from arty to weird to repulsive, with some images closer to Hans Bellmer or Man Ray than to his own Eraserhead. “It was inspired by 1000 Nudes, a book of a thousand vintage nude photographs that were mostly anonymous and had been collected by this German guy named Uwe Scheid,” Lynch explained (Lynch & McKenna 2018, p. 431). “He passed away in 2000, bless his heart, but his son honoured the agreement I had with his father and gave me free rein to work with these nudes.” In the Couch series (2008), multiple exposures of a woman in different positions makes her a ghostly part of the furniture. In two of these, a thin jagged black line traverses the figure as if caused by a negative laser scan. Other nude studies by Lynch are in colour, close-ups where details of a female body become an almost-abstract fleshscape.

The aquarelles in the show are all small and monochrome, as grungy as old cleaning rags. Many have TV antennas scratched into their surface, with distracting non-representational marks overlaid on a mottled ash-grey background. I found them oddly appealing, like the mildewed basement wall in Jan Saudek’s photos.

The drawings in the show are all from the late-1960s to the early 1970s. Those made when he was an art student typically show varying degrees of realism and finish within a single sheet torn out of a sketchpad: areas that are just preliminary sketches adjoin areas worked past an optimal level of detail. It is hard to tell if this was intentional or he was just interrupted by the class period ending. In any case, his efforts in this medium seem to climax in dozens of small vignettes on used matchbooks. Note the use of arches, tunnel entrances, curtains, etc., as framing devices, making the image look like a theatre stage. Many of his lithographs have this same format – e.g., My House is on Fire + Modern Device (2013).

Most of the lithographs are monochrome, aggressively childish and crude. Their titles give a sense of what they are about: Billy Touches Sally, Boy Lights Fire, I Have a New Car, Trouble on Frog Mountain, I Went Over to Suzie’s but I Never Got There, The Monkey Wins a Balloon of Flies, etc. It is hard not to see them as regressions into the mindset of a child (“my childhood years in Boise were hugely important to me”) or, more charitably, as a continuation of his rebellion against norm-enforcing art education. They also suggest that they were made because he enjoyed the process and the setting (Forest’s workshop in Paris), rather than because he wanted to provoke certain feelings in viewers. Here he admits his limitations in painting but his comments are also relevant to lithography:

“Moving paint around with my fingers and letting everything go on automatic pilot I sort of get into – I don’t know exactly what, but I think it has a lot to do with childhood occurrences… I don’t feel that I’ve really gotten in there yet, and the paintings still seem safe and tranquil to me… I haven’t learned to paint the lighter parts of life in a way that’s pleasing to me… I can’t do a whole figure, and I don’t know why that is… I sometimes paint too much of one and then I have to destroy a lot of it… But all my paintings are violent comedies. They have to be violently done and primitive and crude, and to achieve that I try to let nature paint more than I paint” (Rodley 1997, p. 18).

It is clear that he recognises his handmade graphics fall far short of what he achieves in cinema and the crude primitive violent rawness is an attempt to reduce the gap in impact:

“The cool thing about cinema is that it embraces time and sound and, you know, stories and characters, and it goes on and on and on… What you’re searching for is those magic combos of all the elements. And then you get the ‘whole is greater than the sum of the parts’ kinda thing, and then it’s worth the trip” (Rodley 1997, p. ix).

Cinema is a compound medium of sight, sound, words, behaviours, timing and edits. The successful orchestration or integration of these elements creates immersive depth and a richness of experience that lithography, with its single flat channel, cannot equal regardless of the artist’s abilities. Lynch was brilliant at combining sight, ambient sound and pacing in his films, so the lack of ways to apply those skills in the more limited dimensionality of lithography was a problem he struggled with for decades. Obviously, he got something from trying to develop a lithographic “voice” anyway, since he kept at it so persistently.

His paintings differ from the lithographs in usually incorporating found or made objects that break the flatness of the picture and add a sculptural dimension. He also uses putty under – or in place of – paint to make the picture more 3D. Even that modest addition of multidimensionality significantly enhances the work, as do hand-written words on the surface, which provide a parallax perspective. The intelligent organisation of the artworks and video screens on the walls of DOX adds yet more dimensionality, giving his varied approaches to the different media space to interact so a walk through the exhibition gives one a vivid sense of Lynch as a whole person.

David Lynch – Up in flames

19 Jun 2025 – 8 Feb 2026

DOX Centre for Contemporary Art

Poupětova 1, Praha 7

Images from DOX, exhibition Up In Flames, Courtesy of DOX © DOX (and as listed)

References

Keeler, T. (1997). Pretty as a Picture: The Art of David Lynch [Documentary film]. Fine Cut Presentations. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L0BiRF8Ne4E

Lynch, D. & McKenna, K. (2018). Room to Dream. New York: Random House.

Rodley, C. (ed.) (1997). Lynch on Lynch. London: Faber and Faber.

Schied, U. & Koetzle, M. (1995). 1000 Nudes. Cologne: Taschen.

Urban, O.M. (2025). ‘Bylo vidět, že se Lynch na výstavu těší, říká o výstavě Davida Lynche Up in Flames kurátor Otto M. Urban’ [It was clear that Lynch was looking forward to the exhibition, says curator Otto M. Urban about David Lynch’s exhibition Up in Flames]. ParaDOX Podcast, Episode #25, 30 June. Available at: https://open.spotify.com/episode/6zMmC6tJulUkqTEXEi7dtu

Vakrokti (2025). ‘The Disturbing Student Film That Launched David Lynch’s Career – The Grandmother (1970)’ [Video]. YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sa8vHkMqRtI

Wigley, S. (2024). ‘I like to call it experimentation’. Sight and Sound, September. Available at: https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/news/sight-sound-september-2024-issue

After writing feature articles for Artforum in the 1970s, Robert Horvitz joined Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth publications in 1977 as art editor of their magazines before relocating to Prague in 1991. He has exhibited his drawings at museums and galleries in Europe and the US, including MoMA in New York and Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art.