‘I want you to take a glimpse’. This is Bunuel’s opening line from Hornets, the first track in their new album Killers Like Us (2022), the third instalment of a thematic trilogy after A Resting Place for Strangers (2016) and The Easy Way Out (2018).

But what is it they want the listener to see? Named after Luis Buñuel, the band take influence from scenes such as the eye slicing sequence in Un Chien Andalou (1929). Self described as unwilling and unable to play nice, Bunuel comprises indie Italian musician Xabier Iriondo on guitar, artist, composer and producer Andrea Lombardini on bass, Il Teatro Degli Orrori’s Francesco Valente on drums and Oxbow’s Eugene S. Robinson performing vocals. With their cinematic take on the noise rock of bands like Scratch Acid Bunuel are an intelligent vessel for some very primal instinct. They are certainly adept at creating an atmosphere of unease and suspense and on Killers Like Us the band takes these elements and ties them together through extreme music, dark poetry, and sleazy structures – Rock and Roll! Chuck Berry would be proud.

“the hemp cuts deep as we swing swing swing

and you’ll buy what I bought

when the teacher takes what was taught

and drives it straight up the ass of forever” – ‘Killers Like Us’

Bunuel’s riffage is employed in small, repeated bursts, which punctuates the grating discordance and piercing vocals. Robinson delivers the lyrics in a way the listener can understand what he says, the tempo also staying consistent, grounding Killers Like Us in an insistent structure, that grabs with grip tape and boots you down a lost highway. This collection of discordant harmonic and melodical industrial verse seems to place Bunuel alongside horror films such as Halloween (1978) where disjointed panning and twisting cinematic movements disorientate the viewer, similar to the effect on the listener of Bunuel.

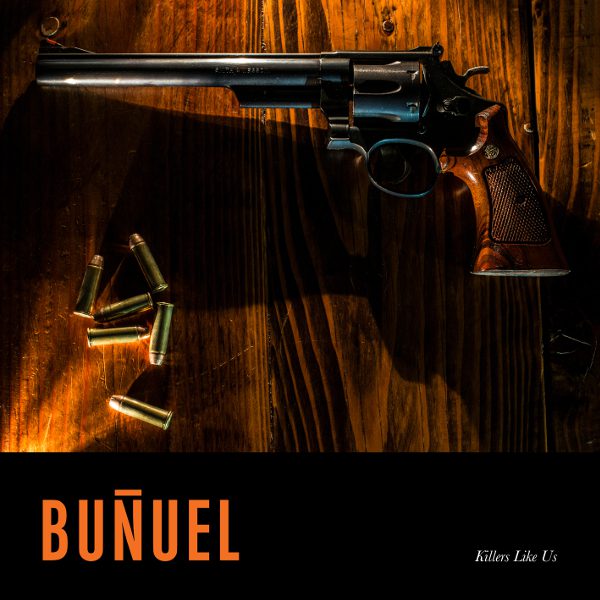

Bunuel capitalises on violent imagery through their videos, artwork and lyrics and this use of horror as a motif, rather than shocking, can be oddly cheerful. There are several major scale romps on the release that feel positively upbeat such as on A Prison of Measured Time. In other places it gets much darker. In the video for When God Used a Rope the use of camera angles is a interesting take on how the different instruments themselves fit together to create a complete scene. Panning and rotating camera angles akin to those employed by Carpenter in Halloween are used to disorientate the viewer, while the female subject in bandages elicits an unsettling feeling of angry vulnerability, suggesting an unpitying exploration of mental health, complete with nodding head and automatic hand.

“The devil is in the details. And the noise and the night and the food you eat and the food you ain’t got,” – Even the Jungle

The phrase ‘devil in the details’ has a double reference, one that evidence of crimes is often found in minute details, the other a reversal of the claim that God is all around us, implying all is evil or nothing of importance. A droning effect achieved from maintained, lengthy guitar chords reinforces a nihilistic message of life’s inherent lack of meaning. It fits neatly alongside punk and horror, such as Rancid’s Nihilism (1994) and American Psycho (2000). The steady tempo, repetitive riffs and drum beats create an order in the chaos, providing both a pleasant listening experience and perhaps a philosophical observation, which seems to serve as an invitation to explore the concept of evil. Horror remains a pervasive element in the listener’s journey through Killers Like Us.

Buñuel investigates philosophical notions of evil, or perhaps the lack of good, through repetition, noise, madness and volume. The very last line of Even the Jungle, ‘while considering the ramifications of what exactly it is that happens when a good man turns bad,’ furthers this claim. The use of the word ‘considering’ promoting philosophical engagement, and the focus on ‘what exactly it is that happens’ not offering an answer but leaving the possibility open for good not existing at all. Killers Like Us doesn’t glorify evil but employs it as an anti-woke narcissistic aesthetic, displaying it as an irreducible facet of an apparently sane society. It is individual and human in an era of market forces, consumer groups, interest allies and all other totalising data-led ranches for consumer cattle. Damn right this music is dangerous, now wipe your mouth and step back.

Featured Image: BUÑUEL (2022) Image courtesy of Bunuel