[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]I[/dropcap]n the UK we make our children choose too early between the humanities and the sciences.

This critique of the UK education system has been current since time immemorial, while the French Baccalaureat is lauded for its more expansive pedagogical reach. The stark division between the arts and sciences was palpable when I was a student and well before the ‘Two Cultures’ furore ignited by C.P. Snow permeated my consciousness.

[quote]permission to ‘fail’

and to make

false starts (and

the documenting of

such mis-steps)

seems to me to

be a resounding strength

of the programme[/quote]

At school I was an inveterate arts lover, thriving on literature, history and languages whilst struggling with maths and sciences, only too glad to exclude chemistry and physics from my GCSE options. At university we humanities students stuck together, with the occasional medic in our midst (“The Medics” had a well deserved reputation for conviviality). But we remained rather wary of “The Natskis” (natural science students) who often seemed a mysterious, homogenous Other.

It was only much later in life that I began to engage with scientific matters and to regret my early feelings of alienation and apprehension in their regard.

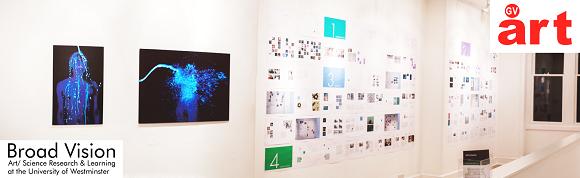

So it was with a distinct feeling of envy that I read about the University of Westminster’s interdisciplinary learning project, Broad Vision. Broad Vision had its genesis at the university in the autumn of 2010 and its aims were ‘to explore student (and staff) exchange across disciplines, encourage the cross-fertilisation of ideas and knowledge, and observe the outcomes…to establish student-centred approaches to learning and teaching through consultation, collaboration and the sharing of skills within and across art and science disciplines.’

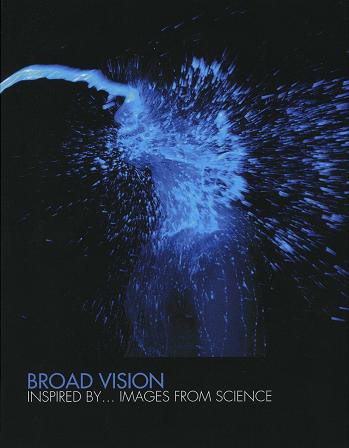

The processes and outcomes of the 2012 programme are documented in a new publication, Broad Vision: Inspired by…Images from Science.

The publication is a hybrid, part exhibition catalogue and part educational treatise, detailing the project’s ambitions, framework, processes and culminations in the shape of an exhibition and associated public events. The book also contains reflections from the participants, both students and educators alike, alongside the project’s educational researcher.

It makes for a compelling and profoundly inspiring read, where an outstanding clarity of pedagogic purpose is matched by the book’s clarity of design, structure and expression.

As Robert Devcic, director of London’s GV Art Gallery observes in his foreword, Art and Science degrees are proliferating in higher education institutions across the UK (University College London, University of the Arts London, and Cardiff School of Art and Design to name but a few). However, the University of Westminster’s Broad Vision programme (which, though it began life as an extra-curricular activity, will be an assessed and accredited module from 2013) is unique in its student-centred approach and the ‘responsive rather than generative’ nature of the curriculum.

The project leader, Heather Barnett, emphasises that rather than prescriptively determining the course at the outset, it is what the students bring to the table in terms of skills and interests that permits an organic evolution to take place. It is based on a strongly held belief that by giving the students a stake in the development of the project ‘they would develop a deeper engagement and a broader reach – in their own and related subject areas’.

This is not to suggest, however, that chaos reigns. The book cogently outlines how the programme was organised whilst still allowing the flexible, responsive ethos. It began with an opening stimulus exercise, before moving into three clearly defined phases of ‘disciplinary exchange, interdisciplinary research and audience engagement’.

The initial stimulus was a collection of diverse scientific images, many of which are lavishly reproduced in the book, drawing on a variety of imaging techniques from microscopy to images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope.

The students undertook a form of ‘speed-dating’ interpretation exercise in which they looked at and discussed the images in pairs (one student from a scientific discipline, the other arts-based, with the pairings changing frequently through the exercise). One student’s observation after the exercise went to the heart of its value: ‘People are used to very different ways of thinking and reasoning, and this process in itself is a very useful experience!’

Following the stimulus exercise came the disciplinary exchange, in which groups of students from within each discipline devised ‘taster sessions’ for all the other participating students, whether conducted as an experiment in a lab or a drawing session in an art studio.

These encounters in new disciplines were the seedbed for ideas and interests to germinate, for conversations and interactions to be cultivated, and for possibilities of collaborative research to be born. Out of this phase six sub-themes were identified (agreed by staff and students in collaboration) around which creative conversations were then fostered.  This allowed the formation of smaller groups of collaborating students who went on to plan and organise their own research proposals. They were supported in this by tutors and facilitators as well as by an online networking platform and forum for the direct and informal exchange of ideas and materials.

This allowed the formation of smaller groups of collaborating students who went on to plan and organise their own research proposals. They were supported in this by tutors and facilitators as well as by an online networking platform and forum for the direct and informal exchange of ideas and materials.

Through the programme visits were facilitated to relevant museums and institutions in London, in order to encourage research skills and a greater familiarity with the resources available throughout the city.

It is clear that these emergent processes, while supported by the safety net of an overarching framework and organising principles as well as tutors and facilitators, have an in-built unpredictability. As Dr. Silke Lange, Director of Learning and Teaching at the School of Media, Arts and Design at the University of Westminster and the Educational Researcher on Broad Vision observes, this makes the programme uniquely well suited as preparation for contemporary adult life. In a world of work that is increasingly changeable, those entering it need to be adaptable and intellectually mobile.

She quotes Stephen Rowland in his book The Enquiring University (2006):

‘In a society that has become increasingly unpredictable it is important that those who teach, as well as their students, acknowledge their inability to predict the outcome of the search for knowledge, rather than pretend that learning can be reduced to the predictable.’

Dr. Lange also remarked that this unpredictability was ‘a catalyst for student engagement and created innovative responses to learning spaces by students as well as staff.’ This is nowhere more in evidence than in the project outcomes. Each of the six sub-themes (Trick of the Light; Catching Time; Fractals and Patterns; Hidden Forces; Little Creatures and Being Human) are represented in the book by the work of several participants, and many of the projects described were striking both in terms of the ingenuity of their concept and execution.

[quote]often in art/science

collaborations it is

clear how the

process has benefited

the arts practitioners;

it is often

more opaque what

benefit the scientists

have gained[/quote]

Whilst some of the work, which ranges from infra-red photographs to fungal sculptures, naturally commands the attention more than others, it is striking how eloquently and rigorously each of the students explain and reflect upon their research project, even to the point, as with several students, of describing the project’s hiccups and even apparent failures. This permission to ‘fail’ and to make false starts (and the documenting of such mis-steps) seems to me to be a resounding strength of the programme and of the book itself.

Microbial Portraiture ‘Masks’ © Mellissa Fisher

So often in art/science collaborations it is clear how the process has benefited the arts practitioners; it is often more opaque what benefit the scientists have gained. The book includes the reflections of a human and medical science undergraduate, Ramon de Assis Figueiredo, who performed a live dissection at the project’s exhibition and it is clear how this was of immeasurable benefit in terms of his confidence in communicating his subject to a non-specialist audience.

It is striking to note that many of the project’s first participants in 2010 returned to collaborate in the 2011-12 programme, suggesting a strong sense of student ownership and investment. Simon Westgate, a participating Photographic Arts undergraduate, neatly articulates the wide-ranging benefits:

‘It is through forward-thinking programmes such as this that higher education will find new ways to enhance the learning experience and create opportunities for students. Outputs such as the exhibition and this book have given us the chance to see our work presented to an audience we may not normally have access to, and to work with contemporaries in fields that we may not normally cross paths with during our time at university.’

It is clear that in Broad Vision the participants revelled in the cross-pollination of ideas and perspectives, in the new and unexpected insights that resulted from collaborative activity across the boundaries of their respective disciplines.

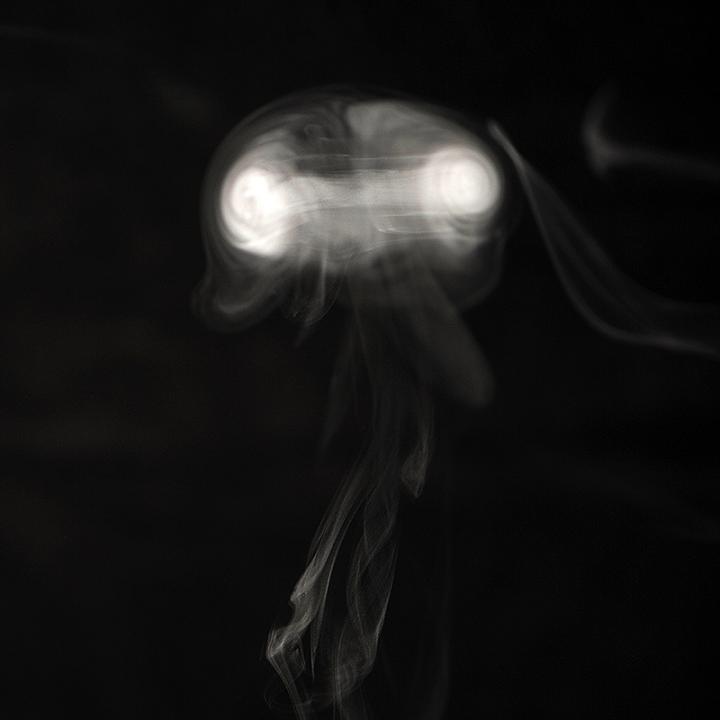

Simon Westgate, ‘Vortex 1’

The value of such an expansive ethos seems inarguable and should, moreover, not be limited to ways of learning; the notion that we can be enriched by understanding how others perceive and frame the world should surely form the foundation of how we negotiate all the worlds we inhabit, whether academic, professional, or indeed, personal.

Broad Vision brings together practitioners from art and science to explore the common ground between them

Unattributed images: Image 1 by Tom Langley, Image 2 by Natalia Janula, Image 3 by Chiara Ceolin

Broad Vision is an art/science research and learning programme at the University of Westminster, engaging students and academics from diverse disciplines in collaborative exchange and experimentation. Through interdisciplinary exploration students become teachers, researchers and producers as they investigate questions relating to biology and psychology, technology and creativity, art and science.

[button link=”http://www.broad-vision.info”] Broad Vision[/button]

Inspired by… Images from Science is the second publication from the Broad Vision team. The richly illustrated volume showcases the work produced and reflects on the project from the positions of participants and observers, offering readers an insight to the processes involved in this innovative art/science learning programme. RRP £16.95. ISBN: ISBN: 978-0-9550951-6-0

The University of Westminster’s Broad Vision project will open an exhibition at GV Art gallery in London on 23 May which will bring together the works of an interdisciplinary group of art and science students engaged in collaborative experimentation and research. The exhibition ‘Data, Truth & Beauty’, which will run until 29 May, explores the integrity and aesthetics of information. It will feature digital investigations into data bending and glitch art; biological experiments with bacterial portraiture and self – illuminating sculpture; psychological studies on the perception of beauty; and creative explorations of the realms of reality.

[button link=”http://www.gvart.co.uk/ “] GV Art[/button]

Broad Vision brings together academics from art and science to explore the common ground between them