[dropcap style=”font-size:100px; color:#992211;”]G[/dropcap]athering together the 200 items (including paintings, textiles and sculptures) for British Folk Art exhibition took the Tate curators to more galleries across the country than normal, Penelope Curtis admitted at the Press View.

The staggering range of geographical locations adds to the spectacular diversity of artworks and objects on display, indicating the broad spectrum of art objects that make up ‘folk art’.

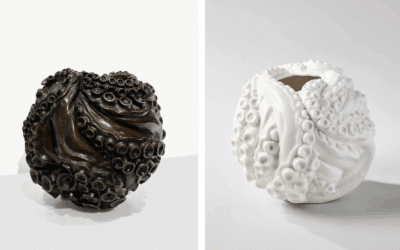

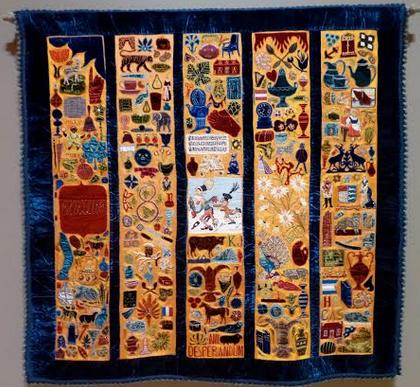

Bellamy Quilt, 1890-1. Pierced and embroidered silk by Herbert Bellamy and Charlotte Alice Springall

Bellamy Quilt, 1890-1. Pierced and embroidered silk by Herbert Bellamy and Charlotte Alice Springall

This genre is particularly undefined in Britain – indeed it is much more of a discipline in America – but instead of attempting to corner off definitions, the curators are keen for this show to be seen more as a “proposition” of folk art that is made up of objects that have histories in galleries.[quote]The anonymity of the artist

or maker is typical of much of folk art[/quote]

Thus, there are also particular viewing histories acknowledged by the exhibition; Curtis claimed that having the British Folk Art show on at the same time as the Kenneth Clark exhibition is appropriate because they both have a lot to do with taste. Notions of class and gender therefore echo throughout these two summer shows and introduce other important themes: that of surplus time and surplus materials, which together, point towards the making context as an ultimate concern.

The idea of excess manifesting in different shapes and forms definitely hits the viewer from the start. The curatorial grouping oscillates between order and chaos, reflecting not only the diversity of the genre and multiplicity of themes, but the variety of making contexts and histories from which the artworks were produced. The anonymity of the artist or maker is typical of much of folk art and this adds to the chaos, as well as challenging our perceptions of art and viewing rituals in art galleries.

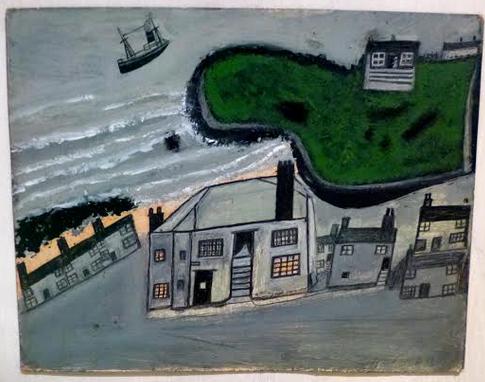

‘The Hold House Port Mear Square Island Port Mear Beach’, c. 1932 by Alfred Wallis. Oil paint on board

‘The Hold House Port Mear Square Island Port Mear Beach’, c. 1932 by Alfred Wallis. Oil paint on board

However, interspersed throughout the works created by anonymous makers are art objects by relatively well-known artists, such as the Cornish painter Alfred Wallis. Even so, artists like Wallis are often left out of many dominant art histories and this sense of exclusion is something the exhibition highlights in a productive way.

Jeff McMillan, artist and co-curator of Tate’s British Folk Art, stated that the first item in the show, a quilt entitled ‘Bellamy Quilt’ 1890 – 1891, is “an index for the exhibition as a whole” because it contains many objects that feature in the gallery’s rooms. Many of the depicted objects are reflected on gigantic scales in the nineteenth-century shop signs on the adjacent wall.

Included in the mix is a giant, clown-like shoe and shiny teapot. The abrupt change in scale and oversized familiar objects create humour and gives a playful atmosphere to the exhibition. It is also interesting to note that the objects portrayed in the quilt are largely from urban narratives. This confronts a common preconceived idea that folk art is about rural – and domestic – activities. With the quilt, a traditional art form and technique are combined with modern subject matter in a particularly thoughtful way.

The making of the art on display certainly took place in unlikely settings and situations. Consider the ‘Bone Cockerel’, a delicately formed object made of bone with intricate, engraved detail on the feathers. It came as a surprise that it was made by prisoners from the Napoleonic Wars held in one of the first prisoner of war camps. With this in mind, the beautiful creature is even more intriguing as we learn it is made of basic, found materials (a common trope in folk art) and leftovers from the camp kitchens.

The suggestion of defiance of one’s situation through producing beautiful art without access to proper materials, let alone tools and blades, is mimicked in the form of the cockerel itself, which is a traditional symbol of France. Although this work was made by a Frenchman, it was made in Britain, and so forms part of the Tate’s collection of British artworks. The prominence that the Tate has given to the ‘Bone Cockerel’ highlights some of the main thematic concerns of the exhibition: Who makes art and how is it made and acquired?

This is a thought provoking, humorous and slightly chaotic exhibition. The combination of different materials, objects, themes, periods and artists makes it a show that you can keep returning to with the confidence that you will be struck by a new thought, detail and perspective each time.

Helen is an independent art critic and curator with an MA in The History of Art from UCL. Her research interests include nineteenth-century French art and ephemeral objects, Rodin’s sculpture and his developments in photography, and contemporary studio craft. She also keeps a blog – helencobby.wordpress.com and a Twitter account: @HelenCobby