The visual arts are inherently interesting. They rest upon assumptions and tacitly inherited traditions that get under our skins. Is there anything that we can think about them that might clarify the relationship between imagination and the role that it has in perception? That is to ask, how do we get clarity in our dealings with something awas rich and as sumptuous as visual art? Let’s start with Wittgenstein pondering the relationship between a mental image and an image that ‘inheres’ in a picture. The two are related notions, Wittgenstein tells us, but although they are akin to each other, they are, nevertheless, distinct. When we look at a picture, we really look. Not so when we have a mental image, no matter how vivid. For we can have a mental image with our eyes closed. There is something to muse over in this.

(courtesy Mollbrinks Gallery)

Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant vexed himself with a peculiar problem that beset the British empiricists. In so doing he set the stage for a schism in philosophy that lingers even today. The rationalists, on the one hand, believed that the true source of all our knowledge is to be found in reason. The empiricists found themselves hampered by the much more commonsensical view that perception is the basis of knowledge (The two views have their roots in Plato and Aristotle, respectively).

A problem for the rationalists is to provide an account for knowledge we gain by observation. The converse problem looms large for the empiricists. For they have to provide an account of abstract ideas. How do we get from our experience of particulars to the regulation of particular observations by the scheme of abstract ideas? How, for instance, do we get from our particular observations of several dogs to the general, governing, single abstract idea of a dog?

Scottish empiricist David Hume thought abstract ideas (of the understanding) were faded impressions of particular sensations – the sort of thing that might clutter up an otherwise tidy mind. One of Hume’s own arguments against this is the ‘missing shade of blue’. This objection considers the possibility of a shade of blue that someone could imagine, even in the absence of having had any particular impression of it. That would mean that we could have an idea that had no basis in particular experience, hence the empiricist doctrine – that all knowledge is based fundamentally in experience – is fatally compromised.

Another Humean doctrine is this: Impressions – the basic elements of experience – are simple and primitive sensations. The ‘ideas’ to which they give rise are to be regarded as faded impressions. However, such ‘faded impressions’ are not sensations at all. If we think now of a darkened vibrant yellow (approaching orange ochre) – imagining that we have only a black and white screen in our sight. In the still silence, we can imagine the clanging piano of John Cale’s ‘Paris 1919’. But the pleasure we take in this imagined activity is better served in complete silence. Hume, in this instance, does not give to perception that which it demands; and permits its leakage into the realm of the imagination.

English philosopher John Locke thought ‘ideas’ to be images in the head: mental images. But Locke still had to answer what it would be to have a general idea, of a dog for instance. If a general idea of a dog is to be formed, somehow, from the various collection of particular dogs we’ve experienced, it cannot be of any one type of dog. (For dogs are of different sizes, different breeds, different colours, and so on). From whence, then, am I to fashion an image with which I am to ‘see’ as a ‘dog in general’?

Irish clergyman and philosopher Bishop George Berkeley complained to Locke, that if the general idea of a triangle is a mental picture, then that picture must itself be triangular. But since all triangles are exclusively either scalene or isosceles, then the general idea of a triangle must itself be neither scalene nor isosceles; for the one would rule out the other. That is not logically possible. Ergo, general ideas are not images.

II

Kant, recognising the problem facing the various empiricist positions, devises a solution which sets the relation between perception, imagination and understanding. According to Kant, we have passive sensations which would include colour, sound, taste, smell and touch. We react to these sensations as do sunflowers exhibiting heliotropism, tracking the sun from east to west during the day. Sunflowers are mindless. In order to perceive our environment, humans need the application of concepts in order to organise their seeing, hearing, tasting, smelling and touching. In the synthesis of perception, the human mind shapes sensation into conceptual taxonomies. The sensations passively undergone are structured by a conceptual framework by the active understanding. At the intersection of sensation and understanding the passive (sensation) is formed into concepts (by the understanding).

However, Kant recognises that he needs there to be a transformation of the passive into the active; and to this he assigns the schema. Kant specifically states that a schema is not an image. However, it provides the rules under which images of particulars can fall under a general concept. In this, we are told, it is like a blueprint or a monogram, or linear sketch. As noted in The Critique of Pure Reason;

“The schema is in itself always a product of the imagination. Since, however, the synthesis of imagination aims at no special intuition, but only at unity in the determination of sensibility, the schema has to be distinguished from the image…

Indeed it is schemata, not images of objects, which underlie our pure sensible concepts. No image could ever be adequate to the concept of a triangle in general. It would never attain that universality of the concept of all triangles… The schema of the triangle can exist nowhere but in thought… The concept ‘dog’ signifies a rule according to which my imagination can delineate a figure of a four-footed animal in a general manner, without limitation to any single determinate figure such as experience, or any possible image that I can represent in concreto, actually presents.” (Kant 1929 B179 – B180)

III

With this in mind, we turn to art’s history. Heinrich Wolfflin wrote Principles of Art History, in which he made a distinction that might well be illuminated by the passages of part II above. Here is Wolfflin on the distinction between the linear and the painterly, which form the basis of the entire book.

“We must go back to the fundamental difference between draughtsmanly and painterly representation… the former represents things as they are, the latter as they seem to be…

Linear style is the style of distinctness plastically felt. The evenly firm and clear boundaries of solid objects give the spectator a feeling of security, as if he could move along them with his fingers, and all the modelling shadows follow the form so completely that the sense of touch is actually challenged. Representation and things are, so to speak, identical. The painterly style on the other hand, has more or less emancipated itself from things as they are. For it, there is no longer a continuous outline and the plastic surfaces are dissolved. Drawing and modelling no longer coincide in the geometric sense with the underlying plastic form, but give only the visual semblance of the thing (Wölfflin 1932, 20-21).

Kant, as quoted, writes of what it is to ‘delineate a figure’, with a schema providing the template for a mental image to be formed. Wölfflin writes of the kind of ‘realism’ that eschews the painterly in an effort to arrive at an image that marries the picture to the concept.

IV

Looking at Agnetha Sjögren’s Dog series, we are introduced to a sculpture that is not of any particular dog. If the work is about anything, it references Jeff Koons’ Balloon Dog series. But his dogs are made of twisted balloons and so they reference the kind of thing that might be conjured at a children’s party. Sjören’s dogs have no such reference. As such, they are better suited to what we are looking for and which we know from Kant’s elaboration, cannot be achieved: a schema that aims at being an ‘image’ of the universal concept of a dog. It is therefore not a representation as such. There is no dog for which her sculpture is an image. And yet… And yet… It is precisely for this reason that she has invented something that permits or contains a level of thought about the very nature of visual representation.

If we’re recognising Marmaduke as a dog, it is reasonable to say that this is an exercise of the visual system. It involves looking as well as thinking (and, in thinking: judging); and yet this recognition does not entail the having of an image. A schema, according to Kant, is where the visual impression (which is passive – the impingement of colour and shape) engages with the understanding, (which is active, ‘it’s a “dog” and not a “cat”’). Yet if this engagement is a mental representation, surely it must mean matching Marmaduke (that particular dog, over there) to something that governs the attribution of the concept ‘dog’. Thus, schemata seem to be visual in some sense.

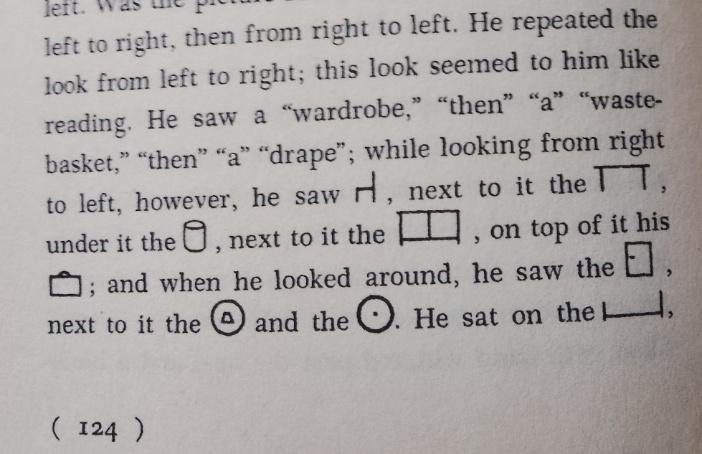

Peter Handke’s The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick, tracks the mental breakdown of a schizophrenic goalkeeper who descends into psychopathic madness. Toward the end of the book his grasp of language breaks down and he begins to ‘see’ things in terms that are neither concepts nor images. These, we might think, signal the breakdown of the schemata that brings together concepts and images. Here, again we might think, we see in the fracture of an image from concept, the nature of the schema in bringing together the two disparate components of the understanding.

V

Jonathan Huxley’s paintings do not have particular human beings as their content. They are paintings of, therefore, non-existents. However, they picture the possible interrelations of human beings. Exploiting the medium of paint to depict these abstractions. Moreover, these paintings are painterly, in Wolfflin’s sense, for they are not about schematising – making diagrammatic abstractions that reveal the outline form of a human being, but celebrate differences in appearance. If they have diagrammatic qualities at all, it is showing the ‘interrelatedness’ of one human to a network of others. Herein lies their optimistic beauty.

Mixed media on canvas 130x170cm (courtesy Galerie Olivier Waltman)

His painting is a celebration of ‘free association’, at a time when this is threatened in some countries. But it doesn’t polemicise or hector. Rather, the unregulated clusters of people are seen as in a dance. In this, they are lovely. Working with narrative, his paintings are benign trackings of conversations and informal, atmospheric mingling of ‘the people’.

Jonathan Huxley, The People (updated), A generative project in collaboration with Stuart Cupit and Solarflare London.

A painter working in another tradition but whose works are also beautiful is David Stubbs. Unlike those who take advantage of the medium’s ability to deal in abstractions. Stubbs, who studied at The Slade in Euan Uglow’s studio, uses paint to make representations of the ceramic bowls and pots that he has made. They are quiet, studious and inherently gentle pictures of particulars. They nevertheless provide us with images into which we have to imagine a world of light and shadow; and of the work it takes to submit the mental image of our looking at a set of objects to fit the flat canvas upon which they are fabricated.

16.5cm x 24.5 cm (courtesy of Amanda Aldous Fine Art)

VI

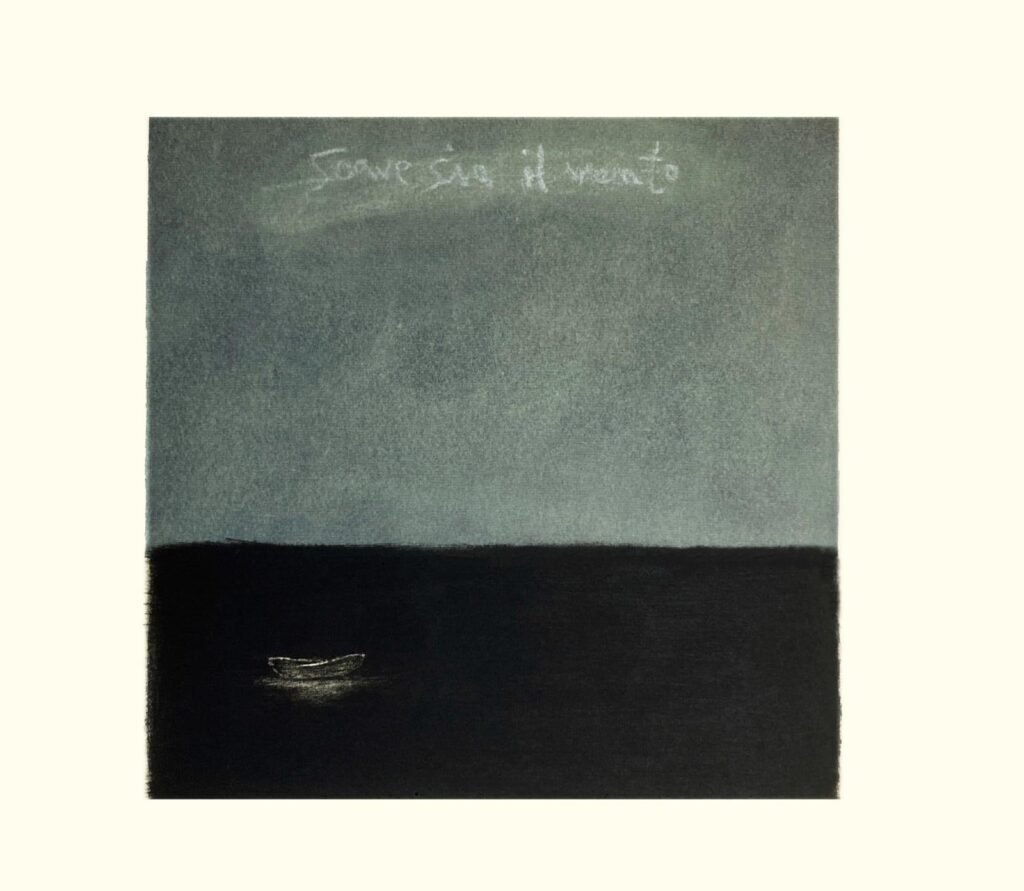

(Series: At An Impassable Border), Two-plate drypoints with papier collé, 45 x 38 cm Sheet, Edition of 8 (courtesy of Julian Page Projects)

The show includes many collections of prints. Julian Page Projects has examples of Rees Roberts’ work and here is one of them. (See the review of his solo exhibition here)

This image is both narrative and imagined. The ‘Impassable Border’, has many associations, not least being the border at which Walter Benjamin took his own life in the small hotel as he was being chased by the Nazis and was held at Port Bou on the border between France and Spain. The image also reminds us of the River Styx, where the dead pay the boatman to ferry them to ‘other side’. It provokes the thought of Hume’s missing shade of blue’. Stygian blue is surely impossible, since it is supposed to be the blue of the sky above the Styx. And since there is no light it is reckoned to be darker than black. That is a contradiction in the ‘logic of colour’ and its systematic possibilities and necessities. It is, amongst Rees Roberts’ many series, an image that fills the viewer with a sense of dread – like a requiem or a fugue, but simultaneously sparks a kind of wonder. Why is the boat empty? Perhaps the boatman and his passenger have drowned. But the dead can’t drown – logic again. But what a lovely, aching picture to wonder at.

VI

Images and the imagination. We owe much to Kant in our struggles to figure out the nature of mental imagery and its relation to the images we see invented by imaginative artists of different stripes. And it is to him that we owe the conception of aesthetic ideas. Ideas that lie beyond the ambit of conceptualisation.

The London Art Fair, Islington Design Centre, 20-25 January 2026

References:

Berkeley G (1710) A treatise concerning the principles of human knowledge, Dublin: Aaron Rhames.

Handke P (1970) The goalie’s anxiety at the penalty kick (trans M Roloff), New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Hume D (1739) A treatise of human nature, London: John Noon.

Kant I (1929) The critique of pure reason (trans NK Smith), 2nd edn, London: Macmillan.

Locke J (1689) An essay concerning human understanding, London: Thomas Basset.

Wittgenstein L (1953) Philosophical investigations (trans GEM Anscombe), Oxford: Blackwell.

Wölfflin H (1932) Principles of art history (trans MD Hottinger), 7th edn, New York: Dover.

Main image courtesy of London Art Fair © Mark Cocksedge.

Other images courtesy of artists and galleries shown.

Mollbrinks Gallery

Julian Page Projects

Amanda Aldous Fine Art

Galerie Olivier Waltman

Ed studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art and later wrote his PhD in Philosophy at UCL. He has written extensively on the visual arts and is presently writing a book on everyday aesthetics. He is an elected member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). He taught at University of Westminster and at University of Kent and he continues to make art.