Continuing from part one here Sverre Malling discusses his Tessa Farmer, his latest works and readjustment in the direction that his work is taking.

Interviewed in late 2025 for our issue on foreign objects (Trebuchet 18: Foreign Objects), Malling answers why he portrays certain subjects in the manner he does.

You’ve spoken about our interest in Tessa Farmer (who you’ve done a portrait of)—what do you like about her work and is there a connection to your own work?

Tessa Farmer is an artist I admire a lot, and I absolutely find that we share interests, themes, and subject matter in different ways, be it explicitly or more in terms of atmosphere and undercurrents. I have even included her in an exhibition I curated myself, and as an artist it is always a source of joy and inspiration to identify other artists with whom you entertain certain affinities or interests. It is almost like discovering a forgotten or unknown relative. Especially if one has felt alone or outside the fold in one way or another, these forms of shared aesthetic DNA can provide a sense of community and relation. Tessa Farmer’s exploration of small, miniature tableaux of bizarre scenarios—stages orchestrated from dead material, such as bugs and insects—resembles a sort of uncanny and grotesque dolls’ house, like a child’s playing field turned outlandish and strange. So, I certainly feel connected to her.

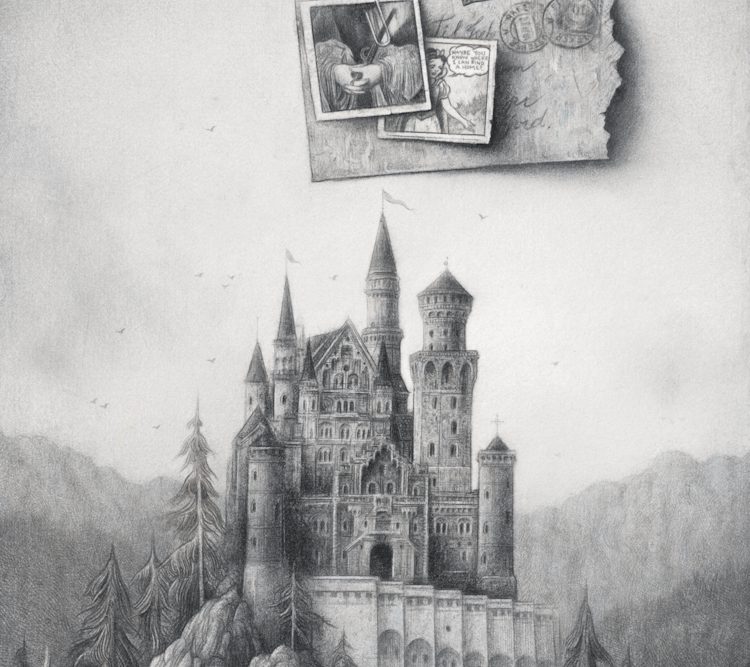

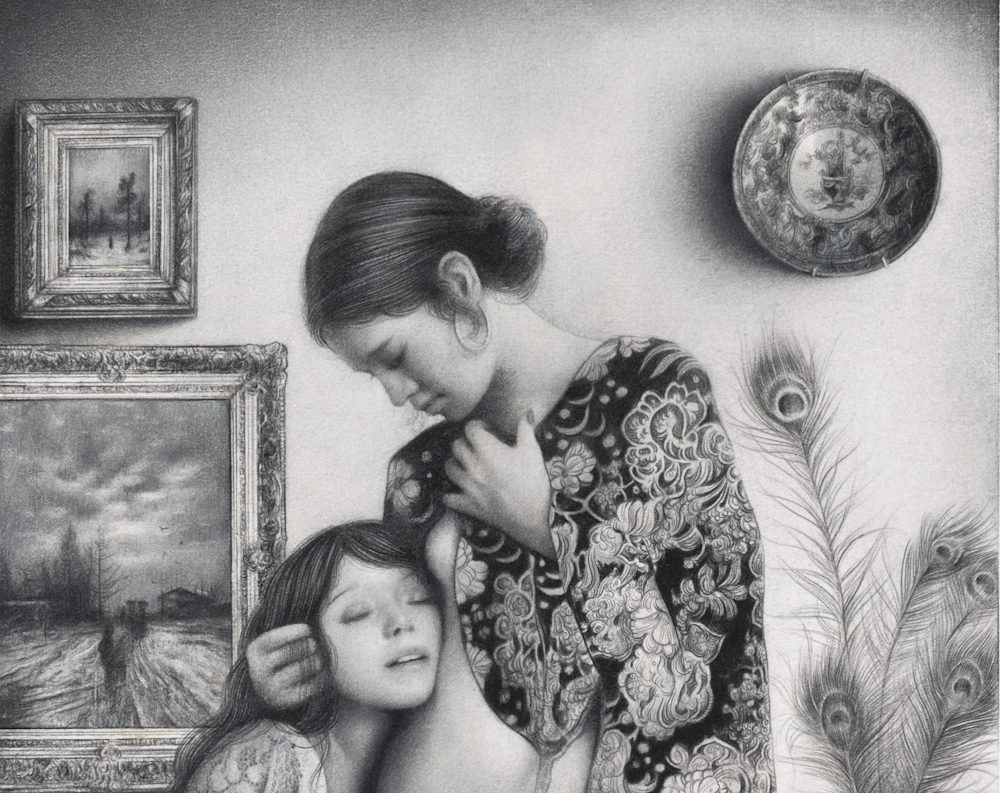

Neuschwanstein/Letter (detail), 2025

For artists with a distinctive style like yourself do you ever feel the urge to break away from what you’ve become known for or is there a thread, a love perhaps, with a method you’ve chosen that you feel compelled to nurture?

I do not feel that I have ever stagnated as an artist, but there has always been development in my approach and interests. Obviously we can point to certain aspects and continuities, but I have never felt that I have landed or arrived at a fixed aesthetic or method. In addition, my sources and inspirations seem to be constantly expanding, so the main issue is that the technique of working with charcoal on paper remains painfully time-consuming. That is a steady source of frustration. So, if I could change anything about how I approach drawing, it would have to be a way of devising an application that is quicker and snappier.

How do you find your source material for your work?

Mainly I read a lot. I have a large collection of academic and scholarly books on a huge number of topics, so this is a steady source of ideas and motifs. Furthermore, I tend to follow these up with digital tools, such as simply Googling certain themes and phenomena. So I basically do research, to put it like that. However, occasionally this process remains more impulsive and spontaneous—the result of concerts, museum visits, walks, conversations with artists and art-critic friends.

You’ve portrayed both historical figures like Algernon Swinburne and contemporary artists like Genesis P-Orridge. What common thread connects these seemingly disparate personalities for you?

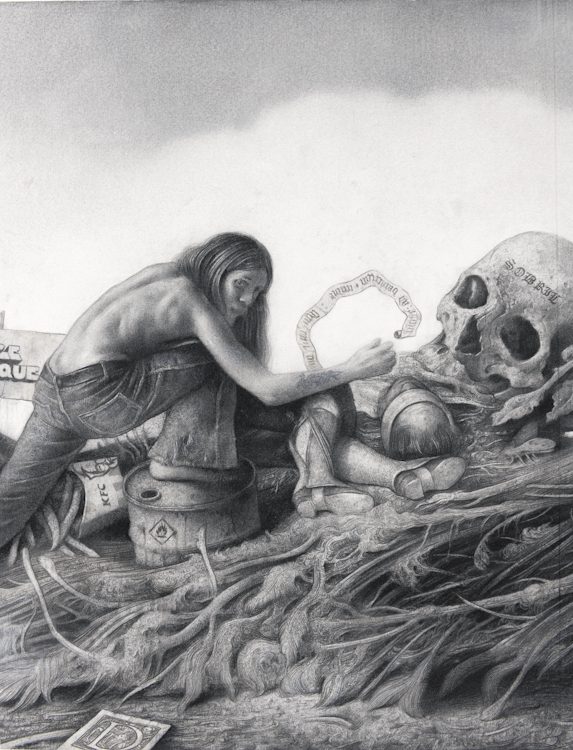

Above all, these figures represented something offbeat and unconventional in different ways. They had visions, artistic or otherwise, which invited the peculiar, curious, and unorthodox. These visions or approaches wanted to shake up our collective consciousness about life and art in ways I found and still find stimulating. Not least, as many of these projects and lives ended up incomplete in some way, unfulfilled, I ask whether there might be some untold and still-relevant stories in this material. These are threads I like to weave together in order to create strange new tapestries of cultural history—the idea that there exists some kind of aesthetic and historical tissue that connects these widely different characters.

You mention shifting between ‘the adult and the childish’ in your work. How do fairy tale narratives help you address serious historical and cultural themes?

There is a tension—a spectrum, I think—between the guileless, perhaps slightly naïve, on the one hand, and the macabre and dangerous on the other when we talk about fairy tales and folk culture; this tension contains seeds of conflict and contention. When translated into my work, these unresolved forces, or this dialectic, produce, I hope, a certain ambivalence—something which feels unresolved in an interesting way.

When you include some esoteric symbols in your work do you connect with their histories and those that they hold with the subjects of your work?

To an extent, yes, but not in a religious or sectarian sense. I do my research and make sure that I understand the framework and contexts of the symbolism I deploy or include. But overall, this iconography becomes symptomatic of a larger interest in the ways in which people have tried to break out of their given situation—the fact that we cannot control who our parents are, where we go to school as small children, where we grow up, and so on. These symbols and emblems you encounter in my work also remain metaphors for this desire to forge your own paths, the conviction that there are other lives we could live, other paths to take, than the ones which are in some way prepared for us by social, political, and cultural circumstance. So these symbols are both concrete, with specific meanings in specific contexts, and also general symbols of this greater kind of freedom.

You reference artists like Theodor Kittelsen and the ‘supernatural and eerie’ tradition in Norwegian art. How has this influenced your approach to depicting non-Norwegian subjects?

There is definitely a relationship or connection, in my view, between Kittelsen and English traditions of illustration and graphic work—for instance figures like Aubrey Beardsley and Arthur Rackham, and all the way to Austin Osman Spare and the imagery of popular culture. But whether or how my interest in an artist like Kittelsen has affected my approach to non-Norwegian subjects is more difficult to elucidate. In general, I can only say that there exists a type of energy or quality which is similar, an inclination or a rapport which needn’t be expressed explicitly by any of these figures, but that I still perceive to be there in some form or other. Beyond that, I don’t think I actively think about this distinction between Norwegian and non-Norwegian subjects as such.

preoccupied and voluntary disorganized, detail), 2024

How do you think your work contributes to contemporary discussions about national identity in art, especially given Norway’s relatively recent cultural independence?

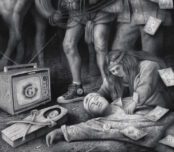

This question invokes, in particular, I think, my work with the exhibition Lazarus og mitt lille lam (Lazarus and My Little Lamb) at Galleri Haaken in Oslo, where I explored ideas of national identity and belonging in a time of increasing polarisation and a loss of collective cohesion. How we negotiate notions of truth, community, and togetherness in a world of fake news and aggressive, conspiratorial rhetoric. The fragmentation of a shared kind of cultural conversation has left us with a string of echo chambers without any form of meaningful interaction. What does Norway and being Norwegian mean at such a time, when we are estranged from nature and from each other? How can we talk about community? I tried to touch upon these tensions.

I’ve heard your upcoming exhibition has a new concept and direction for you, can you tell us more about it? What’s the title? And where did you go with it?

Hmm, no, I don’t yet have a title for the exhibition [ed: At The Mistress’ Request (2026)]. That will probably come soon. And I wouldn’t go so far as to call it a new concept or direction, but rather a continuation and extension of the literary tendency within my drawings. Looking ahead, I’m trying to move in a slightly different direction by shaking off some of the explicitly politicised material I’ve been working with in recent years. Instead, I want to explore the more invisible undercurrents, conflicts, and traditions within art history and visual culture.

The drawing of the peacock is an example of a work that expresses precisely that metamorphosis that my practice is currently wrestling with. The peacock carries the past with it but also sheds it as it moves towards the future. In that sense, I read it as a kind of portal work, marking a shift in how I approach the image itself, which again takes the archive, history, and memory as its sources and metaphors.

Is there a key image from the upcoming exhibition that you think encapsulates where you are artistically at the moment?

I’ve developed a renewed interest in the academic tradition of painters such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, William Bouguereau, Alexandre Cabanel, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Frederic Leighton. These were the most celebrated salon painters of the 19th century, now largely forgotten. They dominated an entire century through a system of conventions and social markers. Then came modernism, with its preference for the original and the transgressive, which effectively swept an entire visual culture aside.

Yet, in their anachronism, these painters still pose important questions and open new spaces, spaces that 20th-century art history largely deemed unacceptable to delve into. This fact fuels my own engagement with this forgotten, and in a way polished and perverse, authority that has shaped our entire concept of conservatism in modern visual culture. We might ask ourselves: which images move us? How do we construct ideas of taste and representation within a culture whose primary mode of expression is polarisation? A renewed look at the foundation of our ideas of canon, social belonging, and identity has perhaps never been more relevant. These are questions that concern me deeply.

How does this new exhibition differ from the work you’ve done previously?

By turning to the art-historical canon, to sources that were once authoritative yet lost public interest with the rise of the avant-garde in the latter half of the 19th century, I want to investigate what stories, ideas, and values exist within the polished, the perfected, the overly refined. Cultures, social groups, and paradigms reveal themselves both in what they make visible and what they conceal. This is a fundamental structure of language itself. As Alfred Lord Tennyson wrote in In Memoriam (1850), ‘For words, like nature, half reveal and half conceal the soul within’.

These are the mechanisms I wish to dissect in detail in my upcoming visual projects. The membrane between the high and the low in art-historical iconography is paper-thin; a hand, a finger, can mark the difference between history painting and pornography. The glamorous, the shiny, the flawless carries something perverse within it, something disciplined and kept in check through social and cultural codes and conventions. Codes and conventions that art and imagery can break, retell, and re-visualise.

Sverre Malling

At the Mistress’ Request

9 Jan – 7 Feb 2026

Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

36 Tanner Street

London, SE1 3LD

Images courtesy of the artist and KHG © Sverre Malling

Read more in Trebuchet 18: Foreign Objects

Featuring: Our Foreign Culture: Exploring Sufism and Post-Colonial Art, Outsider Stars: Sverre Malling. Dalí’s Lobster Phone And The Language Of Desire, Curves Of Thought: Simon Tayler, Bones, Helmets And Uncomfortable Truths: Victor Spinelli, The Inevitable Otherness Of Being Human, Foreign Objects In Local Places: Orobie Biennial, Europe’s Art Weeks Come Together: Spider Network, The Insecurity Collection: National Galleries, The Oracle Speaks In Silence: Ljubljana Biennale

Ex-London based reader of art and culture. LSE Masters Graduate. Arts and Culture writer since 1995 for Future Publishing, Conde Nast, Wig Magazine and Oyster. Specialist subjects include; media, philosophy, cultural aesthetics, contemporary art and French wine. When not searching for road-worn copies of eighteenth-century travelogues he can be found loitering in the inspirational uplands of art galleries throughout Europe.