A first encounter with Kazakhstan is intoxicating, its clashing layers of ancient with ultra-modern, where the familiar meets the utterly strange. The former capital city of Almaty is a highly concentrated crucible of different eras: framed by the ageless splendour of its rugged, mountainous landscape you’ll find here the faded civic buildings and grand boulevards of Imperial Russia butting up against brutalist office and residential blocks from Soviet colonisation. Dominant overall, however, are the skyscrapers, scars and symbols of speculative development—extractive capitalism on steroids. Does this astonishing appetite for economic modernity indicate a country ready for cultural and social revitalisation?

The largest of the former Soviet states, and the last to detach itself from the USSR in 1991, Kazakhstan is the least populated but notably rich in oil and minerals. No wonder it seems to be prospering as it discreetly expands its commercial and political networks to include other partners than Russia, pivoting towards China and Western Europe (The Art Newspaper, 2025). But, like China and Russia, in the 34 years since independence it has filled its major cities, Astana (the new capital) and Almaty, with all the classic Western trappings—mollusc-like clusters of glass and steel tower blocks (mostly in the ‘bulk over beauty’ category), eight-lane superhighways and gargantuan shopping centres. But there’s one 21st-century trope it had seemingly avoided: any platforms for contemporary art. Until now. As of September 2025, Almaty boasts not one but two brand new arts institutions: the Tselinny Center for Contemporary Culture and the Almaty Museum of Art (ALMA).

Launching simultaneously, they are both funded by wealthy private businessmen, but appear to be two very different animals. ALMA is a 10,000 square metre building designed by UK architects Chapman Taylor, muscling its way over the top of Al-Farabi Avenue. With its alternating aluminium and limestone cladding, its façade’s endlessly pivoting perspectives, it has a Guggenheim-lite quality—if Gehry’s Bilbao icon were reinterpreted in Minecraft blocks. The presence of a large Richard Serra in its own vast, dedicated room (albeit not as large as Bilbao’s), a Yayoi Kusama Infinity Mirror Room, and a Bill Viola A/V installation, not to mention the “statement” sculptures on its exterior (by Alicia Kwade and Yinka Shonibare) reinforces the impression of “museum by numbers” (i.e. a collection led by big names) rather than by unusual choices.

ALMA’s owner, the dapper and beaming motoring and shopping centre magnate Nurlan Smagulov (Astana Group, which owns the MEGA shopping center chain, which competes with Esentai Mall, partially owned by Kairat Boranbayev, Almaty 2025), accompanied our crowd of international arts journalists on a tour of his collection of modern and contemporary Kazakh art. One European curator in our midst—very knowledgeable about Central Asian art—was dismissive of the collection apart from a few pieces chosen by the ALMA’s artistic director, Meruyert Kaliyeva (Art History graduate from UCL and Christie’s trained), who also happens to be the owner of Almaty’s only commercial gallery. Conflict of interest or an effort to mix the financially proven with the critically appealing? If the museum’s aim is to generate spectacle whilst monetising its assets, it does so, echoing the administrative concerns of many other world-class institutions. But does it feed the local artistic ecosystem?

Tselinny is a very different beast. A project seemingly designed to do exactly that, its programmes of education and emancipation have evolved over an intensive eight-year incubation. During that time, the key personnel, director Jamila Nurkalieva and artistic director Alima Kairat, have explored a range of collaborative projects with assorted artists and interested supporters—including the UK’s Asif Khan, architect of their long-awaited, newly-delivered building. In the meantime, they have been commissioning exhibitions and conducting conversations around what contemporary Kazakh art of all kinds (music, performance, visual) should and could be, and what kind of building would best support their endeavours.

There is no collection to show off or leverage. Though there is a wealthy backer—Kairat Boranbayev, whose fortune comes from oil and gas, sport, pharmaceuticals and real estate. Considered a ‘colourful’ character, he was reportedly sentenced to eight years in prison in 2023 for embezzlement and money laundering, but appealed and had his sentence reduced after handing over a chunk of his assets, according to The Art Newspaper (2025).

He was very much present at Tselinny’s opening, shaking hands all round and generating bonhomie in the manner of someone who is at ease among footballers (he is chairman of the Almaty team, FC Kairat) as much as fellow oligarchs.But in questions of art, he declared at the opening, he defers to his daughter Alima Kairat, graduate of the Courtauld Institute (BA Art History) and Goldsmiths (MA), He credits her as the instigator of his interest in contemporary art. He just happened to have acquired this former Soviet cinema when the notion to create a contemporary cultural institution first took hold, during the Astana Expo of 2017. In fact, if anyone ever wondered what good an Expo—the world helicoptering in their brightest and best architects and ideas for an international beauty parade and glad-handing extravaganza—does for the host nation, here’s a textbook example.

As designer of the Expo’s UK pavilion, Asif Khan was invited to a talk mediated by Nurkalieva, who was curating a programme around contemporary art as a tool for cultural enquiry and identity. To this end, she had recruited fellow Kazakh returnee, Kairat the younger. It was during his Expo research that Khan met—and later married—Kazakh architect Zaura Aitayeva, who Khan says was also chief architect of the Expo (in collaboration with Chicago-based firm Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture, ArchDaily 2017). He subsequently invested a great deal of time and energy in getting to know this region, guided by Aitayeva. He credits her as Tselinny’s lead architect.

So what of the architecture? A retrofit of a modernist, 1960s Soviet cinema, it fits the West’s prevailing re-use, repurpose narratives. But it’s a reincarnation rather than a refurbishment, as the original elements, including the cinema, were stripped out when the building was turned into a nightclub and restaurant venue in the 1990s and noughties. The overwhelming advice from all the engineers they consulted was to demolish—after all, there was little left of the original, and what remained was structurally compromised (the region is prone to earthquakes). But the team held fast to the notion of reinhabiting this Soviet icon, and eventually found engineers and the technology to help them do it.

The place’s problematic history was part of the attraction for Khan. He told journalists during a press tour: “The cinema was built on the 10th anniversary of Khrushchev’s Tselina campaign (Tselina translates as ‘virgin lands’), the campaign to transform sacred nomadic homelands—the Steppe of the Kazakh people—into agricultural land… And that moment in time had a dramatic effect on the Kazakhstan we live in today. It was the nail in the coffin of a form of life that had endured for thousands of years beforehand, nomadic life. So the name represents something that is quite a catastrophe in these lands. A cinema can have wonderful memories but also be a place where propaganda is shown. Like a lot of things in Kazakhstan, it can have positivity and negativity. This project and the reconstruction is very much about dealing with those past histories.”

It is for these reasons that Khan’s renewed building stays within the original’s footprint. He explained at the press view: “This building lives in the collective memory of so many people in Almaty, we didn’t want to change its size, its familiarity for so many people walking past. It mediates so carefully between the height of the surrounding buildings. Any alteration to this would have upset that balance and changed the continuum that we were picking up on.”

But the new version is infinitely more beautiful, with a frontage of pale, undulating fins intended to evoke a “cloud” through which the visitor approaches the glazed entrance façade. The roof and the floor of this building, we’re told by the ever-poetic Khan, represents “a meeting of sky and earth”—evoking the Kazakh mythological spirits of Tengri and Umai, respectively. The cloud-like screen unites these planes and acts as a device for re-imagining the building and its purpose. During the press tour Khan elaborated: “The power of the cloud is to soften the building. It’s a device that we have to walk through—this thing of confusion, of unknowable form, within this rigid frame. And when we do this we are set in a new state of mind: we are ready to experience art in a different way.”

But what will fill these walls? Nurkalieva talked at the press conference of 30 years of lost Kazakh art, since independence. Asked if there was any educational pipeline of artists for them to work with, she said of Almaty’s Academy of Art: “It teaches painting, drawing and sculpture in a very traditional way, coming from Soviet times.”

It seems that artists with a sense of rebellion or curiosity disappeared off to places like Germany and Belgium—as did the artist currently being showcased at ALMA. Almagul Menlibayeva is quite the star in mainland Europe, having shuttled between Berlin and Brussels for the last forty years. This show is the first ever retrospective in her homeland, however, and the work is invigorating, especially her films and photographic series, most of which reference the many uses and abuses by the USSR of Kazakhstan’s land and indigenous people—from conducting its nuclear testing in one region to the siting of vast labour camps for punishing dissidents in another. Kazakhstan may not be her home any more, but it’s still her core subject.

Some artists stayed put, encouraged by the Soros Foundation-Kazakhstan, which operated in Almaty from 1995 to 2023 (Caliber, 2023). And a few of those who departed are returning, says Nurkalieva: “For example we have worked with Kyzyl Tractor—the most important Kazakh artist collective” (founded in the early 1990s by Vitaliy Simakov). “All the artists in it have been successfully living their lives, but as a collective they were kind of abandoned. They were existing in European institutions, but not really seen here because the State doesn’t care about contemporary art. It’s not part of their strategy.”

The State may not care about it yet, but will a government with reportedly little independent media (Freedom House 2025), and no major political opposition (CIVICUS Monitor 2023) appreciate the challenges to established narratives that Nurkalieva and her team are encouraging—especially if their work gains in profile and popularity? It may have embraced capitalism, but Kazakhstan is still decidedly authoritarian: its first president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, oversaw the transition to independence but then retained power for 29 years, before appointing his own successor (Roth 2019). In 2022, violent protests erupted—and were suppressed with “Excessive force” (Abdurasulov 2022)—however, these issues have been “dealt with” , we’re told by a friendly and exuberant tour guide, Dennis Keen, who runs Walking Almaty. He suggested that the Kazakhs have a special talent for quietly pursuing their own agendas, whilst avoiding annoying their neighbours (as anyone who borders Russia and China might). Another regional insider claims that privately-funded institutions have more freedom than government-run ones.

The opening performance, a near two-hour spectacular of spoken-word, song and dance, titled Barsakelmes, was created with and features a large community of artists, poets, musicians and even a shaman, evoked ancient wrongs, rewriting the extractive past and summoning the spirit of a new, resilient, collaborative age. Obviously, it would mean more to those listening who speak either Kazakh or Russian (still the first language), but it was clearly a declaration of independence, if not protest. Whilst distinctively Kazakh in vibe, spirit and content, Khan might have exaggerated when suggesting it would be like “nothing you’ve ever seen before”. Yes, it was filled with elemental symbolism—salt, water, dramatic lighting to evoke cosmic interventions—a Star Wars steampunk aesthetic and spectacular costumes, but perhaps he’s never been to a Björk gig, nor watched a Eurovision song contest?

It all went down a storm with the Almaty population gathered for Tselinny’s big opening night—sleek-suited men with steely demeanours and svelte women in high heels and floor-sweeping dresses abounded, but there were also many ‘creative’ youngsters in the mix, tattooed and dressed down in barrel leg jeans and strappy vests. A similar crowd turned out for the ALMA’s big opening on the following night—albeit with a higher ratio of glitter to denim, and perhaps more of the extremely rich and impossibly thin.

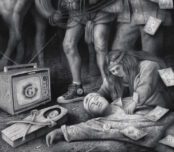

The next day we met a local artist, Nurbol Nurakhmet, who is set for a show at Tselinny next year: he welcomed us to his Almaty studio, revealing some of what he called “non political” work, which seemed pretty political to me: paintings of semi-incinerated state buildings, ‘collaged’ images of people whose tumbling postures were inspired by those he’d seen being dragged away by police from demonstrations. He seemed philosophical about the remnants of authoritarianism and more scathing of the standard of art education in the Almaty School of Art, where he studied (“it teaches nothing more up to date than Picasso,” he said). He supplements his modest art earnings with teaching and mentoring the next generation of students, and praises the current artist community who still “care more about making art than making money”. No prizes for betting on that changing in the next five to ten years, as the profiteering attitudes of galleries and collectors, which both chokes and liberates the contemporary art scene elsewhere, takes hold.

And yet, the streets were clean, the citizens appeared healthy and well educated (a remarkable number of them speaking impeccable English), the motorways log-jammed with new and expensive cars—which, by the smell of them, still burn full-fat leaded petrol. Though the region has its fans among travel aficionados, tourism is still very low key and not, seemingly, a priority. The 30-storey Ritz Carlton, where we stayed—and in which Boranbayev has an interest (Interfax, 2022)—offers a heady combination of scary-looking doormen, badly executed spa facilities, and spectacular views of the development plots around it; you get the feeling people stay there to make money, not spend it. There were plenty of hipster cafés and bars where we could sample both local specialities such as cured horse meat and fermented horse-milk soup, and small, golden doughnuts, served with a dollop of sour cream and honey. But there were also plenty of burgers, chips and an awful lot of bread-based snacks. There was a sense of wealth and opportunity in the air. One of our coterie of international press was heard to mumble, “This feels like the future”, as we were shuttled by minibus from a gleaming new arts institute to an expensive bar. And it’s true: it made the UK’s knackered infrastructure, failing welfare projects and collapsing political system seem like relics from a bygone era. For those of us raised in northern Europe’s former empires, whose international ambition and influence appear to wane with each passing week, it’s becoming clearer that the future is foreign.

Almaty Museum of Arts (ALMA) 8 Al-Farabi, Almaty, Kazakhstan

Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, Masanchi St 59, Almaty 050000, Kazakhstan

References

Abdurasulov, A. (2022) Kazakhstan unrest: “If you protest again, we’ll kill you”. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-60058972 (Accessed: 31 October 2025).

Almaty Museum of Arts (2025) Museum Founder – Nurlan Smagulov. Available at: https://www.almaty.art/museum/history-and-vision/founder-nurlan-smagulov (Accessed: 31 October 2025).

ArchDaily (2017) Expo 2017 Legacy: World’s Largest Sphere. ArchDaily. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/881152/expo-2017-legacy-worlds-largest-sphere (Accessed: 31 October 2025).

Caliber (2023) ‘Soros Foundation ceases activity in Kazakhstan’, Caliber, 4 April. Available at: https://caliber.az/en/post/soros-foundation-ceases-activity-in-kazakhstan (Accessed: 31 October 2025).

CIVICUS Monitor (2023). No real space for opposition activities in ‘new Kazakhstan’. Available at: https://monitor.civicus.org/explore/no-real-space-for-opposition-activities-in-new-kazakhstan/ (Accessed: 4 November 2025).

Interfax. (2022) Kazakh tycoon Boranbayev arrested in Kazakhstan. Available at: https://interfax.com/newsroom/top-stories/76926/ (Accessed: 31 October 2025).

Freedom House (2025). Kazakhstan: Freedom in the World 2025 Country Report. Available at: https://freedomhouse.org/country/kazakhstan/freedom-world/2025 (Accessed: 4 November 2025).

Roth, A. (2019). Kazakhstan president Nazarbayev steps down after 30 years in power. The Guardian. 19 March. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/19/kazakhstan-president-nursultan-nazarbayev-steps-down-after-30-years-in-power (Accessed: 4 November 2025).

The Art Newspaper (2025) ‘As Kazakhstan cautiously strengthens ties with Western Europe new art venues herald a change of direction’, The Art Newspaper, 30 April. Available at: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2025/04/30/as-kazakhstan-cautiously-strengthens-ties-with-western-europe-new-art-venues-herald-a-change-of-direction (Accessed: 31 October 2025).

Images courtesy of ALMA, Tselinny Center, Laurian Ghinitoiu and Asif Khan Studio. © As per caption.

This article was written with travel and hospitality support from Sam Talbot PR, on behalf of their clients, the Tselinny founders.

Arts writer, editor, curator. MSc Environmental Psychology