As featured in Trebuchet 16 (Art and Psychology), Jamie Luoto’s work operates on several levels—not all of them comfortable. Her themes are both dark and incisive; the symbolic aspects of mental crises and resistant frames weave through her work and make the abstract feel personal, perhaps voyeuristic. The sense of poise and tableau that emerges in the way her subjects are presented signals a formal process—a process which one feels reflected in the way she approaches the topics of her paintings. Whether external or personal in inspiration, Luoto’s work guides us through a dark topography of signs that illuminate paths forward.

An artist to watch, this show promises to be another milestone in her upward trajectory. Recommended.

Exhibition Notes: Jamie Luoto – Shadows Of Unseen Grief

Veiled women, black and white cats, the carcass of a hare strung up by its feet, shadows that creep and gnash, that reveal unseen and unresolved presences, emotions and symptoms. Something just beyond the frame, beyond our reach. In Shadows of Unseen Grief, Jamie Lout’s meticulously detailed paintings cast us into a world where sexual trauma doesn’t just live: it expands, unsettles and fragments reality.

Though depictions of grief and anguish abound in art history, visions of women’s suffering have, on the whole, been rendered through careful theatrics, restraint and control – to express emotion can be an act of piety or romance, of sanitised and therefore palatable maternal love, it can be romantic, even desirable but there are rules that have to be obeyed. The emotion must be contained: it must not threaten to seep out into the surrounding world, to shake our unflinching belief in and need for resolution, it must present some kind of finality, a promise of an end. Luoto’s work as a whole pushes back against that narrative, but especially the paintings in this exhibition. These works were born out of what the artist describes as an intense moment of anguish and rupture, and though they were painted after the fact, they are marked by its residues, in some cases quite literally, with surfaces that appear to drip, leak and ooze. In these works, we are not reliving the experience with her, nor invited to try and make sense of it, but rather to just sit in the shadow world that trauma has opened up.

This space is at its most raw and unnerving in Strange Woman, the largest painting in the show, stretching across three canvases that are joined together by hinges to suggest an altar – an image of worship or sacrifice that recurs across several compositions. This painting was the starting point for the exhibition and depicts the artist – all of Luoto’s works are self-portraits – sitting naked on the bed. Though we cannot see her face, we recognise the grief in her hunched posture, her hands clasped to her mouth. Stalks of lavender – a recurring motif in Luoto’s practice, often tied to notions of ritual, calming and cleansing – spill from the bed, a scratch across the smoothness of the surface. Surrounding the bed in a semi-circle, are the glossy translucent forms of condoms, another of the artist’s motifs: the ghosts of trauma, observing or closing in.

Imagery moved between Luoto’s paintings creating a sense of haunting and persistence. In this exhibition, in particular, we encounter several motifs suggestive or hunting or of being hunted. In Strange Woman, mice dart between the sheets, watched by a black cat (the artist’s familiar, but also a predator here) standing on its hind legs; Cherry Hare depicts the corpse of a hare lying on a striped table cloth. Though there are flies on its fur, it appears freshly caught, with no signs of decay. Here, as throughout Luoto’s work, there is the sense of ritual at play – or rather of trauma being transformed into ritual: cherries have been placed in a circle around the animal, some of them eaten, the pips remaining, and again there’s lavender, tied to its feet. Luoto creates clues for her viewers, and here, it comes through a play on word association: the cherries evocative of sex and virginity, the hare suggestive of feminine sexuality, or a metaphorical stand-in for the body itself.

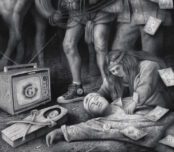

The same imagery is carried into The Swallowing where the ability to grieve is stifled by the nervous system’s overwhelm. Cherries are scattered across the floor of what appears to be some kind of stage. In the spotlight, hunched over the ground, is the figure wearing a white mask. On the curtains behind her, an alternate scene plays out in the shadows, seemingly along her spine: two huge slobbering dogs chasing hares while above them floats a glass of milk on the precipice of spilling. Here, as in several of the works, there is a disconnect between the action or imagery in foreground and what’s happening in the shadows, made all the more unsettling by the ambiguous drips of liquid along the figure’s backside.

The True Becoming and Alone Among the Fallen envision different kinds of masking and performance. The former is a direct reference to The Madonna of Humility with the Temptation of Eve (c.1400) by Olivuccio di Ciccarello with the composition split in two, symbolising the fragmentation or loss of self. In the upper half is the acceptable, masked self, standing within a kind of decorative altar clothed in translucent black veil as if performing an act of mourning or self sacrifice, while beneath lies ‘the whore’ or the subterranean self, enclosed within a dark cave like space where each and worms dangle from the ceiling. Alone Among the Fallen also features a veiled figure – this time a reference to Mary Magdalene as Melancholy (1622-1625) by Artemisia Gentileschi – gazing directly at the viewer with an expression that’s difficult to decipher. The painting references the common belief that Gentileschi’s Mary Magdalene was a self-portrait, layering Luoto’s image with echoes of a historical archetype: the fallen women as a figure of both paint and power. Luoto draws a line from Magdalene’s solitary grief to her own, navigating an intergenerational continuum of shame and survival. But the space we’re drawn into is not entirely public. The intimacy of the scene – veiled, austere and tinged with the colour of mourning – leaves us unsure of our place. Are we being invited in, or are we intruding? The veil becomes a symbol of both transparency and separation: the expression is not theatrical but ambiguous, vulnerable yet withholding. The candle, again only seen in the shadows, is snuffed and smoking – a signal that something has ended, or been extinguished – but without resolution.

Throughout the exhibition, we are brought into spaces where images remain suspended between revelation and concealment, where emotion is not dramatised but insistently present. The detail and lushness of Luoto’s surfaces can be deceiving – suggesting a quiet completeness – but there are works that reward repeated viewing. Eat return reveals something new: a symbol overlooked, a shadow previously ignored. The recurrence of certain images across compositions reflects the circularity of trauma and grief – its persistence, its strangeness, its invisibility to others and its power to distort time and space. These are not spectacles of suffering, but confrontations with its residue: the moments after rupture, when everything appears still, yet nothing is quite right. We are left to sit in that unease, to look – but not without discomfort – and to question whether looking is an act of care, of complicity, or trespass.

Jamie Luoto: Shadows Of Unseen Grief

13 September – 11 October 2025

Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

36 Tanner Street

London

SE1 3LD

Images courtesy of KHG © Jamie Luoto / KHG

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance. – Aristotle